Order Altered States

Table of Contents

CIP's demilitarization program

Order Altered States |

Table of Contents |

CIP's demilitarization program |

|

|||||

|

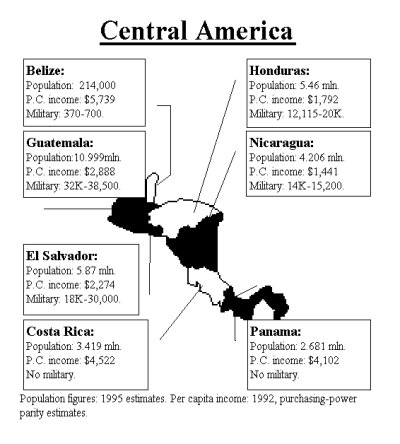

This book’s main argument is new, but simple: since armed forces in regions like Central America are not necessary for security, they should be significantly reduced or even abolished. This might seem a bit drastic or unrealistic at first glance; memories are still fresh of Central America’s years as a "global hotspot," when armed forces were a centerpiece of superpower strategy and the locus of national political power. Recent years, however, have seen dizzyingly rapid change. With continued peace, democratization, and integration, Central America’s existing armies rather suddenly find themselves without a mission to justify their large sizes and political roles.

Central America is no longer at war. Every country in the region is democratic, at least in form; all seven have seen at least one peaceful transfer of power between freely-elected leaders. Central America’s presidents and their cabinets meet several times a year, coordinating policies and ironing out differences long before they become conflictive. As the traditional security threats recede, attention is shifting toward underlying social and economic problems. Meanwhile armies, where they exist, are voluntarily undergoing modest cutbacks and yielding some of their power to civilian rulers. Put together, these processes are creating a rare and robust opportunity for historic change—including the change that this book recommends.

The military in Central America

Such an opportunity is virtually without precedent in the region’s history. Central America’s militaries have largely dominated social and political life since the second half of the 19th century.

At that time (in the five countries that were independent), landed elites were pursuing "nation-building" projects, seeking to create European-style states out of territories marked by anarchy and warlordism. Their efforts included the founding of armies to defend their states’ sovereignty and territorial integrity from frequent internal and external threats. With little resistance from almost constantly divided elites and nonexistent civil societies, several of these new forces expanded quickly beyond their original mission.

Supported by powerful, usually wealthy civilians,

armies came to consider themselves the embodiment of national

character, the arbiters of political power and the often brutal

enforcers of their view of the social good. This self-image was

accompanied by growing corruption, abuse of human rights,

impunity, and an utter lack of professionalism. Modeled on and

aided by the armies of Western Europe and the United States,

Central America’s military institutions came to bear little

resemblance to them.

Supported by powerful, usually wealthy civilians,

armies came to consider themselves the embodiment of national

character, the arbiters of political power and the often brutal

enforcers of their view of the social good. This self-image was

accompanied by growing corruption, abuse of human rights,

impunity, and an utter lack of professionalism. Modeled on and

aided by the armies of Western Europe and the United States,

Central America’s military institutions came to bear little

resemblance to them.

As their power expanded in the 20th century, armed forces took complete control of the state. Dictators could not rule without them; frequently, the dictators themselves were officers. Civil-military relations in twentieth-century Central America were marked by antagonism, corruption, and repression. Only Costa Rica’s civilians found a solution: that country’s armed forces were abolished in 1948.

The cold war provided armies with both a mission to justify their dominance and—through massive United States aid—the means with which to assert it. Under the U.S.-inspired national-security doctrine, Central America’s armed forces, however undemocratic their behavior, were seen as a bulwark against Soviet, and later Soviet-Cuban, totalitarianism.

U.S. military aid and cooperation, both of which intensified following the Sandinistas’ 1979 victory in Nicaragua, turned the region’s militaries into well-equipped anti-Communist war machines with unquestioned control over their societies. Between 1950 and 1990, the U.S. lavished its Central American allies with at least US$2.4 billion in military aid, while the Soviet Union provided Nicaragua’s army with several hundred million dollars in assistance during the 1980s.

With superpowers providing the rationale and the materiel, the region endured a decade of bloody civil wars in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua. The results were horrifying: deaths during the 1980s numbered at least 200,000, 2 million were displaced, and citizens of every country but Belize and Costa Rica—even those not at war—suffered systematic murder at the hands of government security forces.

A changed security outlook

By mid-decade, the region had bottomed out. Peace finally began to take root in 1986; the presidents of Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua signed an accord in Guatemala City in August 1987 (known as "Esquipulas II") committing their countries to democratization and negotiated peace. As the cold war drew to a close on the world stage, so did Central America’s hot wars. Nicaragua’s contra rebels laid down their arms following elections in 1990. El Salvador’s government and rebels signed a sweeping accord in 1992, making theirs the first civil war in the hemisphere this century to end by a peace agreement. After nearly a decade of talks, Guatemala’s government and rebels finalized an agreement in December 1996. Democracy came to Panama as well, on the heels of a controversial U.S. invasion to remove a former cold-war ally, Gen. Manuel Antonio Noriega—an event that also set the stage for the dissolution of Panama’s armed forces.

These changes brought the abrupt disappearance of the very threats which justified the buildup and dominance—if not the very existence—of Central America’s militaries. Today, as the old, military threats recede, armies are visibly searching for new reasons not only to exist at their present strength, but to exist at all.

Among traditional threats to sovereignty and territorial integrity, their search is far from fruitful. The near-term danger of civil wars and insurgencies essentially vanished with the cold war. Border conflicts and territorial claims, while several, are low-level, fundamentally diplomatic problems that are vastly overshadowed by current advances in regional cooperation and integration. Quite simply, no existing security threat, potential or actual, demands a military response.

Faced with the irrelevance of their traditional missions, Central American militaries are turning toward new threats. In public statements and interviews, officers express concern about phenomena like poverty and inequality; rapidly-rising common crime; the presence of international organized criminals and narcotraffickers; the persistence of ethnic divisions; environmental deterioration; and public institutions’ lack of credibility and effectiveness. There is nothing new about many of these threats, as Central Americans have been living with them for centuries. What is new, however, is the idea that, despite democracy’s advance, militaries might have an institutional responsibility to combat them.

Unsurprisingly, after decades of dominance and foreign aid several militaries may indeed be the best-equipped of all state institutions to confront these new threats. Armies enjoy such distinct advantages as oversized budgets, a cheap labor force, and (if their leaders are so inclined) the ability to ignore inconvenient laws with impunity. Civilian state sectors, atrophied by decades of playing a secondary role, do not enjoy the same discipline and national reach.

This does not mean that Central America’s new threats demand a military response. A government that claims to represent the popular will cannot rely on its least representative institution to solve its most pressing social problems. Since democratization demands the military’s subordination to civilian power, it would be counterproductive to boost military power by assigning new roles. Civilian institutions—ministries, legislatures, judicial systems, police forces, civil-society organizations—will be strengthened only through concerted action against these threats.

Built up for the security needs of the past and inappropriate to the needs of the present, Central America’s militaries have shed significant numbers of troops since their 1980s peaks. All, however, remain a great deal larger than they were even during the 1970s. Military budgets—particularly hard to justify in a region where 60 percent of the population lives in grinding poverty—have shrunk somewhat compared with ten years ago, but remain a multiple of their pre-1980s levels.

Armies’ impact is also felt in ways that are impossible to quantify. Fear of an institution capable of abusing human rights with impunity keeps citizens from making full use of the guarantees laid out in their nations’ democratic constitutions. The military’s status as an unelected "extra branch" of government with broad veto power over civilian decisions severely circumscribes political discourse and skews state policy toward the high command’s preferences. Links to crime, maintenance of privileges and prerogatives, and separation from civilian institutions—civilian courts not least among them—are continued challenges to the solidification of democracy and the rule of law. Increasing holdings in the private sector may represent unfair competition, autonomy from civilian authority over budgets, and the creation of a new economic power base.

At the same time, the armed forces’ historical patron, the United States government, continues to maintain close links with the region’s militaries. To its enormous credit, the U.S. has deeply reduced overt military funding to Central America. Yet close contact is actively maintained in several areas. The United States encourages an expansion of military roles to combat some new security threats, particularly narcotrafficking. Joint military exercises and humanitarian civic-assistance activities, along with instruction at the School of the Americas and other U.S. installations, represent extensive inter-military contact to the exclusion of civilians. A largely unknown measure of assistance and other support continues to reach Central American officers through intelligence agencies. Finally, the U.S. armed forces still occupy bases in both Panama and Honduras. These activities—and the impressions of approval and credibility that they convey—contribute strongly to the persistence of disproportionately strong armies in a region of impoverished democracies.

A chance for change

Despite these formidable challenges, present conditions are still propitious for the region’s demilitarization. A definitive end to the hour of Central America’s militaries will nonetheless require that these countries overcome several challenges, chief among them:

A new definition of "security"

The traditional notion of "security" that justified the keeping of large armies—namely, organized external or internal threats to territory and sovereignty—is not very useful today, as such threats have almost completely receded. The region does not lack security threats, however: the well-being of most Central Americans continues to be threatened by phenomena ranging from poverty and inequality to crime and human-rights violations. As part of an overall transfer of security responsibility to civilians, fighting these new security threats should become a purely civilian task.

Strengthening democratic institutions

The recent progress toward democracy must not be reversed. Democratic institutions will only blossom if civilian control over the military is complete. If they are to exist, armies’ role must be limited to that played by their counterparts in democracies with more successful histories of civil-military relations: the defense of national territory and sovereignty. The armed forces should have no internal-security role whatsoever, except when so ordered by civilians because civilian capacities are clearly exceeded. The impulse to turn to the army to solve social problems must be deterred by comprehensive improvements in the capacity and efficiency of civilian state institutions.

Collective-security arrangements

The possibility of external aggression, though extremely slim, cannot be discounted—if only because militaries, which are accustomed to employing worst-case threat analyses, often claim it as a justification of their present sizes and roles. The 1946 Inter-American Reciprocal Assistance Treaty (the "Rio Pact"), which commits the hemisphere’s countries to protect one another from external attack, reduces this justification’s validity. Costa Rica has successfully invoked the pact several times to maintain its territorial integrity during its half-century without an army.

The Rio Pact should be updated, relying less on strictly military measures and offering specific reassurances to demilitarized states. An auxiliary arrangement between the Central American countries would increase the credibility and certainty of a collective response to aggression.

Effective civilian police forces

Civilian police capacities should be substantial, and their maintenance should be a high priority. In recent years, both El Salvador and Panama have built civilian police forces virtually from scratch; as of this writing, it appears that Honduras and Guatemala will soon undergo similar processes. Making such transitions successful requires, first and foremost, an unambiguous understanding of the fundamental differences in structure, doctrine, and training between a civilian police force and a military. Success also depends on generous funding and a great deal of technical support from the international community, a comprehensive training program whose curriculum is grounded in respect for human rights, the presence of effective and duly-empowered internal discipline and monitoring bodies, and the maintenance of an ethic of community service and public trust. The experiences of those making the transition should offer numerous lessons not only for the rest of Central America, but for nations worldwide seeking to establish civilian dominion over internal security.

Provisions for demobilized soldiers

Further reductions in the region’s armed forces will thrust thousands of jobless men and women on economies that already have excessive levels of unemployment and underemployment. Worse, most of these future ex-soldiers will have no marketable skills, other than combat and killing. The destabilizing potential of disgruntled ex-soldiers has been evident in both El Salvador and Nicaragua, where reintegration programs’ mixed success left many to opt for violent means of both survival and protest.

As with police transitions, future demobilizations can learn much from past experiences, replicating successes and avoiding failures. Funding must be sufficient, again with international community involvement. Skills training and the recovery of weapons must begin even before soldiers leave the barracks. Land distribution programs must avoid red tape and ensure the availability of sufficient credit. Training and microenterprise support must be demand-driven and decentralized, with programs designed together with recipients and the communities they re-join.

A supportive U.S. policy

As democratization continues, the past and continuing behavior of Central American armed forces will eventually force the United States to make a choice. U.S. policymakers must decide whether they are to maintain their links to the region’s militaries or whether they are to support its civilian, democratic institutions. Continuing to do both is ultimately counterproductive.

A middle course of action cannot work: "professionalization" or the encouragement of "moderate" officers does not bring the military to divest itself unilaterally of its powers and privileges. Instead of clinging to Central America’s generals, the United States could instead become an unequivocal proponent of its civilian democratizers. Open U.S. support for reduced military roles (rather than the role expansion being encouraged today), accompanied by an end to military collaboration, would bring the region vastly closer to democracy and stability.

Replication of this experience elsewhere

Central America is only part of a sizable contingent of developing countries emerging as democracies following authoritarian rule and/or civil war. (Other examples can be found in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and the former Soviet Union.) The Esquipulas process, which was set in motion even before the cold war ended, gave the Central American nations a sort of "head start" over other countries undergoing similar transitions. Central America, to a great extent, has served as a "laboratory" for peace-building and democratization initiatives—election monitoring, UN peacekeeping, demobilization, construction of a civilian police force—that have since been replicated elsewhere.

Demilitarization, too, could be replicated elsewhere, as the arguments favoring it in Central America are just as compelling in several other parts of the world. As the region crawls out from under its militaries, the world would do well to watch closely, evaluating how this experience could be repeated in future contexts.

Acknowledgments

This book emerged from a joint project carried out by the Center for International Policy, based in Washington, D.C., and the Arias Foundation for Peace and Human Progress, based in San José, Costa Rica. The CIP-Arias "Security and Militarism in Central America" project involved an extensive primary-research phase, in which investigators carried out archival work and dozens of interviews with U.S. and Central American leaders. This was followed by two conferences in 1995—one in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, and one in Washington, D.C.—in which the results and implications of our research were discussed and debated. Our work was supported by funding from the Bydale Foundation, the Canadian Development Foundation, the Compton Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the United States Institute of Peace, and the Winston Foundation for World Peace.

Our organizations are grateful to many people for their contributions. Contributions by W. Frick Curry, Cristina Eguizábal, Anne Grant, Hal P. Klepak, Joaquín Tacsan and Fernando Zeledón were absolutely crucial as this book took shape; their observations and insights are evident throughout the text of the final product. The team of investigative journalists at Hombres de Maíz, coordinated by Miguel Díaz Sánchez, gathered an enormous amount of primary information from interview subjects in every country of the region.

The staff at both of our organizations did an excellent job of managing the project’s progress and providing needed information. Jennifer Haefeli of the Arias Foundation, who managed the project during its research and conference stages, played an indispensable role in guaranteeing its success. During the writing stage, CIP intern Stephen Hamner complied with dozens of requests for often obscure information and edited early versions of most chapters. The Arias Foundation’s Carlos Walker, Kevin Casas and Arnoldo brenes were instrumental in shepherding the project through its latter stages.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Joaquín Tacsan. Joaquín, the director of the Arias Foundation’s Center for Peace and Reconciliation, was a good friend to all who had the pleasure to work with him on this project. Joaquín was a passenger on a Boeing 727 that crashed in Nigeria on November 7, 1996. We remember Joaquín for his easygoing nature, his sharp intelligence, and his fierce dedication to the causes of peace and democracy—not only in his home region of Central America, but throughout the world. His death is a painful blow to all of us.

Order Altered States |

Table of Contents |

CIP's demilitarization program |

|

|||||