« After next Tuesday: three scenarios | Main | Take down this web page now »

November 04, 2004

A post-Election Day look at Ricaurte, Nariño

A side effect of election results like last night's is a minor, momentary crisis of confidence for some on the losing side. When a majority of your fellow citizens ratifies a foreign policy you strongly oppose, it's only natural to ask - probably while lying awake at night - "Am I missing something? How do so many not see the obvious danger, the likelihood of failure, the need to change course now? Are they blinded by ignorance, ideology, or propaganda? Or could it be me?"

If that has happened to you, don't worry. It's easy to make that flash of doubt vanish in an instant. All you have to do is read a newspaper, visit some websites, stay informed.

For example: if you ever have even the faintest feeling that the Bush and Uribe governments could somehow, possibly, be on the right path, simply scan the day's news in Colombia.

One item in this morning's news did it for me. The IndyMedia Colombia site had posted an alert from the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC) about the disappearance of Efrén Pascal, a leader of the Awá indigenous group in Nariño department, in Colombia's far southwest. Members of the FARC's 29th Front kidnapped Pascal, the governor of the Awá nation's Kuambí Yaslambí community, from his home in Ricaurte municipality (county) in the middle of the night on October 24. Even a 250-person delegation organized by the Awá People's Indigenous Unity (UNIPA), the ethnic group's advocacy organization, was unable to free or find him.

The alert struck a chord because I know some of these people - I paid a visit to the UNIPA's headquarters in Ricaurte back in April. While I've seen many examples of the human cost and unintended consequences of Plan Colombia and the Uribe security policies, the largely unknown situation of the Awá people is one of the most disturbing and urgent.

|

|

Nariño and Ricaurte.

|

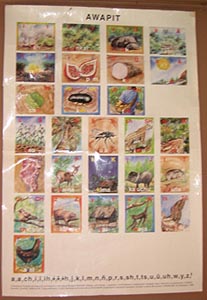

Ricaurte straddles the main road between the city of Pasto and the busy port of Tumaco, about halfway between the high Andes and the sea. The municipality is big, stretching all the way to the Ecuadorian border. Indigenous groups, particularly the Awá, make up 85 percent of the 14,000 people scattered across Ricaurte's very rugged terrain. Colombia's 22,000 Awá people live in 11 communities, or resguardos, in three municipalities (Ricaurte, Barbacoas and Nariño). More live across the border in Ecuador. Their language, Awapit, is still widely spoken, and UNIPA has helped develop an alphabet to accommodate some of its softly spoken consonants - a project that Mr. Pascal, the kidnapped governor, helped to spearhead.

Together with colleagues from several Colombian and Ecuadorian human rights groups, I met and shared lunch with leaders of UNIPA. (I don't know whether Mr. Pascal was present; he may have been, as he is a member of the organization's board.) The group's leaders told us this was the first time any human rights groups had ever visited them.

We apologized for arriving at midday, nearly two hours late. They told us that it was for the best, since guerrillas and police had been fighting just that morning at a site about ten minutes away. Ricaurte is a violent place: its position on the Pasto-Tumaco road places it along a strategic corridor for the movement of drugs and weapons. All of Colombia's armed groups are present, and significant plantings of coca are in the countryside.

|

|

The Awapit language.

|

The spike in violence, the group's leaders said, is a very new phenomenon. Their part of Colombia had gone largely untouched by the conflict until very recently. "This was a tranquil zone," one UNIPA member said. "It was safe to travel through the countryside. ... We had a way of life that was functioning well, with our language, our traditional medicine, and a tight social fabric." Though a small ELN presence had established itself in the general area by about 1995, illegal armed groups were unknown.

Plan Colombia changed all that. In 2000-2001, the United States began pouring millions of dollars in military hardware, training and herbicide fumigation into Putumayo, the department about six hours' drive to the east. Putumayo was the main focus of Plan Colombia's first phase; at the time, it had more coca than any of Colombia's other 31 departments. Spray planes and a U.S.-funded army counter-narcotics battalion fanned throughout Putumayo's coca fields, destroying the crop. It did not take long for many Putumayo coca-growers, and the armed groups and narcotraffickers who buy from them, to pack up and move westward to Nariño, especially the coastal zone just west of Ricaurte. By 2003, the UN reported (PDF format), Nariño had replaced Putumayo as the country's number-one coca-growing department. As it has done many times since major spraying began in Colombia about ten years ago, the problem moved to a new zone.

The Awá leaders told us they had never seen coca until Plan Colombia began pushing it out of Putumayo. People began arriving from Putumayo in 2000-2001 and buying up land, even in the indigenous group's reserves, offering astronomical prices. Coca-growing expanded dramatically. In an area where people had traditionally lived on subsistence agriculture, earning perhaps $1-2 per day on sales of food, a strange world of brothels and discos sprouted up overnight, particularly in zones like Llorente in Tumaco municipality to the west.

|

|

A view of Ricaurte.

|

Our UNIPA hosts admitted that some Awá had planted coca too - particularly younger people tempted by the easy money - but that they only planted tiny amounts, enough to produce perhaps a few grams of coca paste per harvest. The paste sells for 2,500 pesos (about $1) per gram, a price that they said had not risen over the years despite U.S.-led eradication efforts (fumigation, they said, has occurred in waves arriving about every nine months since 2001).

As Plan Colombia pushed the coca westward into Awá lands, violence quickly followed. The FARC showed up for the first time in 2000, at about the same time as the coca. The paramilitaries' Pacific Bloc was not far behind. Guerrilla presence and violence grew sharply worse in 2002, as the end of the Pastrana-era peace process, and the Uribe government's military offensives elsewhere, pushed greater numbers of FARC into this more remote zone. The army, which had been utterly absent for years, established itself in 2003, as part of the Uribe government's efforts to secure strategic roads.

The armed groups, competing ruthlessly for drug money and access routes, have hit the Awá people exceedingly hard. Both the guerrillas and paramilitaries routinely blockade and displace populations. Dozens of indigenous people have been killed, both by selective assassination and by getting caught in the crossfire. Rape is common. Armed groups routinely steal money, livestock, crops, and even clothing. Blockades have had a devastating effect on a zone where malnutrition levels are already high; the guerrillas have made it impossible to maintain flows of food aid from the World Food Program and the Colombian government's Social Solidarity Network. In June 2003, the FARC killed an Awá governor who had tried to facilitate some of these shipments, accusing him of helping paramilitaries.

"You are the owners of this land, but we make the rules," a local FARC leader told UNIPA. The guerrillas prohibit travel after 6:00 PM. Both sides suspect anyone who travels - even from the rural to the urban part of Ricaurte - of spying for their opponents. Even a few minutes' detention and questioning by the military or paramilitaries may mark one as a sapo (snitch) in the eyes of the local FARC.

What of the Uribe government's vaunted Democratic Security policy, which has sought to protect citizens from this kind of violence through increased military presence? An Awá leader put it well: the increased presence is "only good if you happen to live near the highway," where most soldiers and police are deployed. In fact, the military and police presence in larger towns and roadsides has served only to push the guerrilla and paramilitary presence farther into remote, neglected zones like the Awá resguardos, making conditions markedly worse.

For their part, the indigenous leaders said, the army and police themselves have done little to win the local population's trust. Residents are treated as likely terrorists; even wearing rubber mud-boots, carrying more than a little cash, or lacking an identity card (a cédula, which many indigenous do not have) may mark one, at a military or police roadblock, as a guerrilla. Several recent combats between the military and guerrillas have taken place in small Awá towns, amid a terrified population; in February, as the ONIC has denounced, the Colombian air force apparently even bombed an Awá school in Ricaurte. Meanwhile, nobody we asked could cite an example of soldiers fighting paramilitaries.

After four years of Plan Colombia and two years of Democratic Security - two strategies that have pushed drugs and violence from other zones to their once-peaceful lands - the Awá people are reeling. Many are displacing, leaving for Pasto, for Ecuador. A fiercely independent and well-organized group, the Awá, usually through UNIPA, have repeatedly sought to denounce abuses and plead for help before various Colombian government institutions, with almost no response. The government's non-miltary presence in rural Ricaurte remains virtually nil.

Awá leaders did not hide their consternation when I told them that my country's aid to Colombia was 80 percent military and police assistance. "Plan Colombia should be all social aid," they said unanimously, as if that were the most obvious thing in the world.

We still await news on governor Pascal's whereabouts. Rumors that he had been killed were proved false earlier this week. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights' Bogotá office has called on the FARC to release him immediately. ONIC and UNIPA are demanding the same. Though the guerrillas and paramilitaries have a poor record of responding to international pressure and outcry, CIP adds its voice to those urgently calling on the FARC to immediately release Mr. Pascal.

Faced with the overwhelming evidence of places like Ricaurte, and the evident suffering of the Awá and many others in similar circumstances, we repeat our calls for an immediate and fundamental reconsideration of U.S. policy toward Colombia. We fear that too many vulnerable Colombians - who, like the Awá, have the misfortune of living far from the roads and the towns, and far from the gatherers of optimistic statistics - are quietly becoming indirect victims of both Plan Colombia and the Democratic Security policy.

What we have seen in places like Ricaurte makes a crisis of confidence impossible, no matter what the election results tell us about public opinion in general. We will stay informed and active in the new political climate, and we hope that you will too.

Posted by isacson at November 4, 2004 12:09 AM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://ciponline.org/cgi-bin/mt-tb.cgi/13

Comments

I can't hope to adequately understand your feelings,since this appears to be a matter rather close to your heart, but I concur that this is a very important blog article because it sums up the overall situation in Colombia as whole by using a single example. It clearly shows some of the vices of all sides involved. (though there's little to celebrate...I also wanted a Kerry victory. I guess that the concepts of "Leadership" and "Morality" won out, even if they are very misguided in their application).

A policy with a mostly military and barely social composition can't possibly hope to improve the situation for many rural and indigenous colombians, it will indirectly make life far worse for them (while only providing small improvements to urban and city dwellers). It also shows, once again, the counterproductive effects of a similarly repressive drug policy based on fumigation and little else. The crops will always find new fields and, ultimately, they'll keep coming back. Something really needs to change here...and it probably will. The questions remain "when and how".

I also clearly join you and your fellows in urging that the FARC free the governor, which they might or might not do, depending on the circumstances (while they seem to let the indigenous off a bit more sometimes, when they show signs of independent civil resistance...obviously that's not always going to work though...especially since he's in a position of authority).

Posted by: jcg at November 4, 2004 08:45 PM

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)