« Paramilitary Talks (6): Extradition and the U.S. role | Main | Simón Trinidad's extradition »

December 17, 2004

A drug-policy advisor resigns

Two months after the fact, I finally found a copy of the resignation letter (PDF format) of Alberto Rueda, who was a drug-policy advisor to Colombian Interior and Justice Minister Sabas Pretelt until October, when he quit in frustration over U.S. and Colombian drug policy.

Rueda, who had previously worked in Colombia’s defense and foreign-relations ministries, as well as the human-rights ombudsman’s office, made headlines in Colombia with his public decision to resign. His letter, on Ministry of Interior and Justice stationery, makes several thought-provoking – if not downright troubling – points about an anti-drug strategy that is clearly not working.

The letter takes the form of a 27-page memo, which is too long to translate here (and often lapses into the staid style of the career bureaucrat). I offer the following excerpts below, though, because it’s a compelling read.

“Mr. President,” the missive begins, “I have decided to make the document I sent you on October 19 into an open letter asking for a true course change away from the current anti-drug policy. … Colombia may be devoting all of its efforts against this scourge [of drugs], but it is an effort in the wrong direction, incomplete and without hope of ending this agony anytime soon. … The emphasis on zero tolerance and fighting – mainly militarily – against supply has diverted us from a balanced vision, one requiring equal results in demand-reduction and a full understanding of the shared responsibility between drug-consuming and producing countries.”

Europe’s role

“The [Uribe government’s] ‘democratic security’ policy continues Plan Colombia (Pastrana/Clinton) as a central element of the fight against illegal drugs, under U.S. tutelage and financing. … The paradigmatic activity in this fight has been the fumigation of illicit crops, which aspires to spray a minimum of 130,000 hectares [about 325,000 acres] per year. … Plan Colombia was a policy developed bilaterally by the United States and Colombia, excluding very important international actors like the European Union and other developed countries which, had they participated, surely would have placed us in a more balanced situation. We shouldn’t be surprised, then, by these countries’ lack of enthusiasm for supporting the current drug policy. This helps us to understand our difficulty in obtaining resources from them.”

Lack of coordination and balance between strategies

“The Colombian government suffers from a vacuum of management and coordination of the fight against illegal drugs. … For example, we are ill-served by a plan to interdict precursor chemicals when the institutions of security, customs, and financial control lack a clear policy, sufficient budget, and an appropriate operational program to carry it out. In addition, the budget must balance priorities: while the outlay for crop substitution is almost insignificant, the aerial spraying program has millions at its disposal. Truly noteworthy results will not be obtained if we fail to take actions against every link of the chain, with equal effort and efficiency. To think that we will resolve the problem of illicit drugs just with fumigation is a mistake.”

Fumigation in Colombia’s national parks

(Something that, Colombian Interior-Justice Minister Sabas Pretelt warned last week, is not out of the question)

“The results of the 2003 illicit-crop census carried out under the SIMCI 2 agreement reveal some thought-provoking statistics. [SIMCI = Integrated Illicit Crop Monitoring System, a collaboration between the Colombian government and the UN Office of Drug Control and Crime Prevention. It’s a useful resource.] National parks were not fumigated in 2003, yet the amount of illicit crops within their borders continued to decrease, as they have done since 2001: from 6,057 hectares in 2001 to 3,790 in 2003. This calls into question the thesis that the only way to reduce these crops is through fumigation: in national-park areas and buffer zones, the Environment Ministry instead carried out frequent consultations with communities and recent migrants (colonos). However, the threat that this success in national parks could be reversed, and that the expansion of crops in indigenous reserves could worsen, is more latent than ever. The reduction of supply through fumigation could raise the price of the product, while the President of the Republic has declared that lands where these crops are found will be expropriated. Combine these two factors and the pressure to cultivate in parkland will be hard to contain, given its legal status as public land that belongs to nobody and thus cannot be expropriated.”

Fumigation’s declining effectiveness

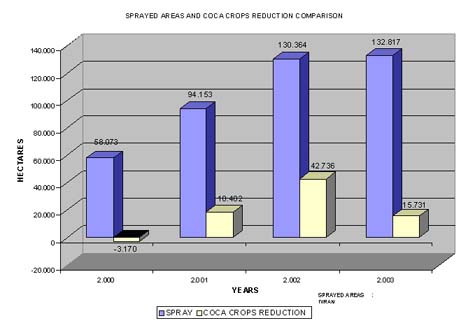

“Of all years since 2000, it was 2003 that showed the worst results in terms of reduced coca cultivation, and was the year in which that reduction cost the most.

a. Coca reduction was almost two-thirds less than in the previous year, and the least of the past three years. Comparing reduced hectares of coca with the intensity of fumigation, we see an inverse tendency: 132,817 hectares fumigated brought an effect of only 15,731 hectares less coca.

b. There is a presence of new crops, or an increase, in zones that aren’t characterized as empty or isolated from the country, such as the provinces of Caldas, Boyacá, and southern Antioquia.

c. The costs (borne by the United States) of reducing coca crops by fumigation have been the highest in 2003, if we compare them with the 16,000-hectare reduction. Conservative estimates establish that fumigating a hectare costs $626. If we multiply that by the number of hectares sprayed – 132,817 – we get a total of $82.5 million. If we divide this figure by the 15,731 hectares reduced, we get $5,243 per hectare. … This figure is what one would expect from such an unequal approach instead of an integral strategy: the obvious effect, a marginal success in the fight against drugs. … To give us an idea of what fumigation has cost in 2003, let’s conservatively compare it with the annual budget of several government entities. It equaled, for example, the annual budget of the Agriculture Ministry; the annual budget of the Ministry for the Environment, Housing and Territorial Development; or twice the annual budget of the National Housing Fund. And even though the purpose of this document is not to question U.S. aid, these figures contrast with the headlines of success promoted by the U.S. Department of State, which are repeated by the media both in that country and in Colombia. The U.S. contributors are wasting their money with this strategy.”

Fumigation’s impact on health

“With regard to health, the fumigation strategy lacks solid arguments to defend it against claims of negative effects on health and the environment. This is so much the case that the Colombian government has just signed an agreement with the OAS to carry out an investigation of fumigation’s effects on health and the environment. That is to say, we do not really know its effects, and as we act blindly, a certification from the U.S. Secretary of State argues that fumigation is not harmful to Colombians. … Only now, after so many years of aerial fumigation of illegal crops in the country, we have barely begun a program of public-health training and vigilance over pesticide intoxication. But there is no certain date for getting results anytime soon, as an active search is taking place for 100 samples that then have to be completed clinically and undergo laboratory and epidemiological analysis. The result is that the Colombian government has been applying – and even more seriously, intensifying – its fumigation program, even though we are not clear about its health effects. And there is an even more worrisome ingredient: the National Health Institute study is oriented toward determining acute effects, such as effects on mucous membranes and skin, but not toward chronic effects, such as evaluating possible genetic alteration or cancer. … Together, we have observed the industrial security measures taken by those [contract workers] who manipulate these chemicals at the airbases where fumigation takes place. They work covered in impermeable yellow safety suits, with gloves and masks. Herbicides are herbicides, Mr. Minister.”

Fumigating legal crops when planted with coca

“It is easy to conclude that the campesinos’ strategy of planting illegal crops alongside legal ones is intentional, but this does not make it legitimate for the government to apply a summary punitive measure like generalized fumigation. If the campesino or cultivator breaks the law with said crop, this must be punished like any violation of the law, and it should be, as is logical under the rule of law, the result of a judicial action, in which said campesino can defend himself and the judge can determine a fair punishment. But the state cannot apply a summary punishment of fumigating the crops they depend on for food.”

The aerial interdiction program

“The aerial interdiction program that re-started in August 2003 contemplates the shooting down of aircraft suspected of transporting drugs. In the opinion of this advisor, this is unacceptable. It is inadmissible and we must reject the notion that the air force can shoot down an aircraft on suspicion of transporting drugs. That is nothing other than a summary execution.”

A proposed alternative

“We must steady ourselves behind the idea that Colombia should promote, before the international community and within the framework of the United Nations, the thesis of regulation of the use of illicit drugs (a model similar to the recently approved Framework Convention on Tobacco Control), as the most effective mechanism for taking money away from the financing of war, not just in Colombia but in relation to international terrorism and transnational organized crime. This proposal is an alternative to both absolute prohibitionism and total liberalization. … The best policy, then, is that which takes resources away from narcotraffickers and terrorists. We would be presenting not just the only possible policy in terms of the realities we face, but also the only policy that is socially fair and politically balanced.”

We congratulate Mr. Rueda for his honesty and for following his conscience, at the cost of a comfortable career in the well-funded world of drug-war decisionmaking. We hope that he will continue to raise his voice.

Posted by isacson at December 17, 2004 11:58 AM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://ciponline.org/cgi-bin/mt-tb.cgi/28

Comments

As far as fumigation is concerned, I've never liked this policy and I never will (and its health effects on both legal crops and human beings), so I can easily agree with the bulk of the advisor's statements on that subject. I definitely believe that alternative methods of fighting drugs need to be promoted both by Colombia, the U.S. and other foreign governments, if real results are to be expected and achieved.

Thus I logically agree that total prohibition is a bad idea (personally, while I hate the use of drugs on principle, I'd tolerate anything from the proposed regulation to outright legalization), that really needs to be looked at carefully and, hopefully, reformed and/or abandoned.

However, his opinion on the aerial interdiction program is by far the least substantiated of the entire paper (even reading the Spanish version). Provided that the necessary precautions are taken to prevent mistakes (they weren't taken in the case of Peru and the infamous attack on the missionaries, I believe, but I don't remember any similar incident happening in COlombia), then I see little wrong with it. If drug flights don't comply with the adequate instructions and warnings from either pursuing aircraft or ground control, and instead insist on trying to escape, then they should be forced to land or shot down (as a last resort), rather than being allowed to flee with impunity.

Posted by: jcg at December 17, 2004 01:53 PM

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)