« Antonio Navarro: "Fumigation?" | Main | Pity the paramilitary process participants »

February 06, 2005

Why is this man crying?

The man in the picture is retired general Jaime Uscátegui, one of the highest-ranking Colombian military officers ever to face indictment and a criminal trial (as opposed to a dropped investigation or a dismissal) for a human rights case. Uscátegui could get up to 40 years in jail if a Bogotá civilian court finds that he knew about, and did nothing to prevent, a grisly July 1997 paramilitary massacre in the hamlet of Mapiripán, deep inside FARC-controlled territory in south-central Colombia.

The man in the picture is retired general Jaime Uscátegui, one of the highest-ranking Colombian military officers ever to face indictment and a criminal trial (as opposed to a dropped investigation or a dismissal) for a human rights case. Uscátegui could get up to 40 years in jail if a Bogotá civilian court finds that he knew about, and did nothing to prevent, a grisly July 1997 paramilitary massacre in the hamlet of Mapiripán, deep inside FARC-controlled territory in south-central Colombia.

In this image from nearly two weeks ago, Uscátegui has just been asked for the name of the paramilitary leader who ordered the massacre. The general tearfully responds, “I’d rather my children have a father in jail than a father in a tomb.” Later, he indicated that the massacre’s mastermind was among three paramilitary leaders who, amid much controversy, addressed Colombia’s congress in July. Everyone understood this to mean Salvatore Mancuso, the AUC leader who has been a prominent presence in the current negotiations with the Colombian government, and who is accused of planning the massacre from a ranch in San Pedro de Urabá, hundreds of miles away from Mapiripán in Colombia’s far northwest.

That Mancuso may have coordinated Mapiripán is not exactly earth-shaking news. Far more interesting – especially to those of us whose government has donated billions to Colombia’s security forces – is the nature of the military-paramilitary cooperation that made it possible.

Uscátegui claims to know a lot about that relationship. In July 2003 recordings that were revealed last March in the Colombian newsmagazine Cambio, Uscátegui threatened to tell all unless the high command helps to keep him out of jail.

If I go to court, it will be a much more serious case than number 8,000 [the term used for the mid-90s narco-money scandal that almost took down President Ernesto Samper]. In fact, it will be more serious than everything that has happened in Colombia. With this issue [the Mapiripán massacre] I discovered what is really happening. It is very serious, very grave, because it proves an allegation that we have denied for all our lives, the one about the military’s links with paramilitaries. … It seems that in the attorney-general’s office, in the inspector-general’s office, in the presidency, they know that terrible things happened there, very grave things for the army and for the country. And that these things could even bring down Plan Colombia.

In the tapes, Uscátegui mentions a computer recovered from the nearest military base to Mapiripán. On the hard drive, with U.S. decryption assistance, was found a wide assortment of paramilitary documents, from the pamphlets the local fighters handed out to their internal rules and bylaws.

So far, however, Uscátegui has hardly followed through on his threat. His trial has revealed little that is new about military-paramilitary collaboration, either in general or as it played out in Mapiripán.

The massacre

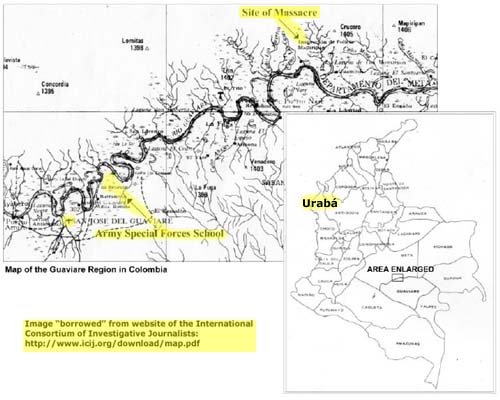

The Mapiripán massacre, which began on July 15, 1997 and lasted for several days, was one of the worst of the hundreds of massacres Colombia has suffered during the past twenty years. It took place in a market town of about 1,000 people, a port on the Guaviare River. Mapiripán was a key link in the coca economy of a longtime guerrilla-held zone, a remote area on the border between Meta and Guaviare departments. (Mapiripán, incidentally, is now in the middle of the zone where the “Plan Patriota” military offensive is taking place). Though the town was less than 2 hours’ travel from significant-sized military bases, the paramilitaries were able to take several days to murder thirty civilians (some estimates go as high as 49), closing all outside access, shuttering all businesses, and methodically combing through the town with a list of people to kill.

Mapiripán was more than just another example of wanton slaughter: it was also a big strategic step for the paramilitaries. Until then, the right-wing militias were a phenomenon largely confined to northern Colombia (Antioquia, Córdoba, the Magdalena Medio, a bloody mid-1990s foray into Urabá). This was their first move in southern Colombia, in an area of vast jungles and plains whose population, mostly made up of recent arrivals, had grown accustomed to the uncontested dominion of the FARC guerrillas. The paramilitaries would soon be all over southern Colombia, facing no military resistance as they came to contest lucrative coca-growing zones with the FARC.

To get there, the killers had to charter two planes from northwestern Colombia, halfway across the country. The planes, a Russian aircraft and a DC-3 loaded with about 20 people each, landed in the nearest airport, San José del Guaviare. I was at that airport in January 1998, six months after the massacre, and there are two things worth mentioning. First, everyone who gets off the plane has to sign in with the police; yet for some reason the arrival of two planeloads of armed, camouflage-clad fighters didn’t appear in the police registers. Second, the airport is located alongside a counternarcotics police base which, at the time, was the only place in Colombia where the U.S.-funded fumigation program, with its spray planes and DynCorp pilots, was operating.

(These personnel were vaguely aware that something was up on the day of the massacre, according to a 1998 letter [PDF format] from the State Department to Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vermont): “The Embassy has reported that U.S. personnel involved in counternarcotics programs at San Jose remember seeing an unusual number of Army personnel at the airport on the day in question.”)

The fighters were met outside San José by about 180 more recently recruited local fighters, split up in groups and traveled by both land and downriver. The fighters arrived in Mapiripán and set about their work for days. Mapiripán’s judge made anguished calls to the nearest military battalion, back in San José del Guaviare. The colonel in charge, Hernán Orozco, says that he had no troops at his disposal but called and sent memoranda to his superior, General Uscátegui, whose 7th brigade was responsible for Meta and Guaviare. The calls for help appear to have died in Uscátegui’s office.

The Barrancón Special Forces base

But there’s more, says investigative reporter Ignacio Gómez, who published a rigorously researched investigation in El Espectador, with assistance from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, in 2000. The paramilitaries who traveled by boat would have had to pass the Colombian Army Special Forces base and training school at Barrancón, built with U.S. assistance in 1996 on an island in the Guaviare River, just downstream from San José del Guaviare and its airport.

According to Uscátegui’s testimony of two weeks ago, “This base [Barrancón] was a fortress. It was located seven kilometers [4 miles or so] from San José del Guaviare. How is it possible that the paramilitaries, in their passage along the Guaviare River, could pass through the [riverine] checkpoint at the base’s entrance without being detected by the highly trained professional soldiers stationed there, who had been given such powerful weaponry?”

The paramilitaries’ passage by the Barrancón checkpoints would not have occurred at a routine moment. From May to July 1997, the base had some foreign guests: members of the U.S. Army’s 7th Special Forces Group who were carrying out “military planning” training with the Colombian Army’s 2nd Mobile Brigade. (It is possible that U.S. personnel left shortly before, and returned shortly after, the period in which the massacre took place.) This brigade was headed at the time by Col. Lino Sánchez, who is currently serving a jail sentence for abetting the Mapiripán massacre.

Col. Sánchez was new to his post, having just assumed command of the 2nd Mobile Brigade in May 1997, the same month the U.S. Special Forces team arrived in Barrancón. His immediate predecessor was Carlos Alberto Ospina. By the time the Mapiripán massacre happened, Ospina was out of the area, heading the 4th Brigade in Medellín, capital of the department of Antioquia, where Álvaro Uribe was serving as governor. In October 1997, troops under Ospina’s command helped make possible another of the worst mass killings in recent Colombian history, the paramilitary massacre at El Aro in northern Antioquia. Gen. Ospina is now the commander-in-chief of Colombia’s armed forces.

The fate of whistleblowers

What happened to Col. Orozco, the battalion commander who relayed his concerns about Mapiripán to Gen. Uscátegui? He was sentenced to thirty-eight months in prison for “failing to insist” that a superior officer act. “They convicted me for informing on a general, and by extension, offending all generals,” he told the New York Times. His career ruined, he now lives in Miami.

Orozco's case is an object lesson for would-be whistleblowers in the Colombian military. A similar fate befell Col. Carlos Alfonso Velásquez, who testified against Gen. Rito Alejo del Río, the head of the Colombian Army’s 17th Brigade in Urabá in 1996-97. A region near the Panamanian border, Urabá at the time was suffering a brutal campaign of paramilitary massacres and displacement that effectively moved the strategic zone from guerrilla to paramilitary control. Gen. Alejo – known on Colombia’s right as “the pacifier of Urabá” – had his headquarters in the town of Carepa in northern Antioquia. At the time – again – the governor of Antioquia was Álvaro Uribe. Col. Velásquez, who served as Gen. Alejo’s chief of staff, testified that his boss maintained contact with paramilitaries and ordered troops to cooperate with them. Gen. Alejo was kicked out of the army in 1999; Álvaro Uribe was keynote speaker at a dinner in his honor shortly afterward. Col. Velásquez saw his career come to a swift end as well; he is now a professor at the Opus Dei-run Universidad de la Sabana north of Bogotá. Being a human-rights whistleblower in the Colombian military has little to recommend it.

As should be apparent, the Mapiripán story is one with a meandering plot and a lot of tangents. The massacre and its aftermath seem to be a limitless source of hints and shreds of information about the linkages that existed, and may still exist, between elements of the Colombian military, paramilitaries, politicians and other powerful figures. (It also offers inspiring examples of the police and military figures who believed in their institutions’ mission and who tried to break these linkages, at times at the cost of their careers.) What we still don’t know about these sinister relationships, however, could fill a very compelling book – a book, perhaps, that would strike at the very foundations of U.S. policy toward Colombia.

Can a "Truth, Justice and Reparations" bill reveal the rest of the iceberg?

Seven and a half years after Mapiripán, Gen. Uscátegui’s testimony is interesting, and offers more tantalizing clues. But it does not live up to the promise of his earlier threat to lay bare the entire arrangement that created and sustained paramilitarism in Colombia. The general still leaves us with a strong sense that we’ve barely scratched the surface.

We’re probably not going to learn much more from trials in which retired generals, afraid for their lives, are driven to tears. But there may be another way, as part of an overall effort to dismantle paramilitarism in the context of the AUC negotiations.

Many Colombians, including much of the human-rights community, are frustrated that so much remains unknown or unproven about who are complicit in paramilitarism's rise, growth and persistence. On the other hand, many of the Colombian military’s backers are outraged that officers like Uscátegui and Lino Sánchez are facing 40 years in jail for facilitating crimes like Mapiripán, while the actual planners and trigger-pullers – the paramilitaries themselves – may end up serving no more than ten years, more likely five if they fully confess their crimes. (The main competing versions of an eventual "Truth, Justice and Reparations" law to govern the paramilitary demobilizations – the Uribe government’s bill and legislation introduced by a multiparty group of congresspeople led by Sen. Rafael Pardo – would require no more than ten years in prison for crimes against humanity.)

A possible solution may be in the Pardo legislation. According to Congressman Luis Fernando Velasco, a backer of the bill cited in Semana magazine, the draft law “contemplates that accomplices or those who somehow collaborated with the paramilitaries’ actions can benefit from the prerogatives that the law would offer [such as reduced sentences], as long as they tell the truth and admit their collaboration with these crimes.”

Since we haven’t yet seen the exact language of the Pardo bill, which was formally introduced in Congress late last week, it is unclear how explicitly this offer to the paramilitaries’ outside “accomplices and collaborators” is spelled out. However, if combined with (a) a requirement that demobilizing paramilitaries reveal what they know about their support and financing networks, and (b) a real prosecutorial effort to go after the individuals whose names emerge from these testimonies, a provision like this would do a great deal to identify those – whether in the military, the business and landowning elite, or in the drug underworld – who made common cause with AUC leaders, backed massacres and displacements, and thought they would suffer no consequences for doing so. We might know, for instance, whether Mapiripán was the work of a few bad apples or a strategy vetted and approved by powerful people in Urabá, at Barrancón, in Medellín, or in Bogotá.

And that, I fear, is why the Uribe government will oppose it vigorously. Better to have a couple of generals in tears, after all, than hundreds – or even thousands – of people identified as patrons of paramilitary terrorism.

Posted by isacson at February 6, 2005 10:45 PM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://ciponline.org/cgi-bin/mt-tb.cgi/51

Comments

And that would definitely be a fair assessment to make, at this point in time.

However, in such an important, sensitive and controversial subject one must thread very carefully, in the interests of both finding out the real truth, assigning true reparation and of staying true to the principles of fairness and reason.

Not just because a relatively huge number of public and private figures will end up being rightfully involved in this bloody and shameful mess (referring to the paramilitary phenomenon and its consequences), but because the lines between the different degrees of responsibility that must be afforded to each individual are very thin and subjective here indeed....

These things should not be taken lightly because sometimes those lines are either deliberately obscured or artificially fattened for political purposes, among other things. Neither of which is appropiate at all and does nothing to favor the truth nor the victims.

How guilty and responsible for Maripipan (or El Aro, for example) is someone who either did nothing to prevent it (or to follow up on the matter) or provided a semblance of potential politico-ideological support to these actions, but didn't personally participate in them?

I personally have to state that I am no judge, thus I have no idea of how to appropiately assign these sort of responsibilities without being found as either too soft or as too aggressive.

Hence hopefully the Pardo bill or something equivalent to what you are mentioning eventually ends up help to fill the legal and factual vaccum.

Posted by: jcg at February 6, 2005 11:26 PM

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)