« A job nobody wants | Main | Don Berna and the drug war »

September 29, 2005

Fumigating parks: the worst environmental risk isn't "Round-Up"

After months of study, the Colombian government may soon announce that it will allow U.S.-funded counter-drug fumigation planes to spray herbicides over the country’s national parks. On September 15, Interior Minister Sabas Pretelt acknowledged that plans and guidelines for such spraying have been finalized. National Police chief Gen. Jorge Daniel Castro told the Associated Press this week, “We’re waiting for the order” to start spraying in the parks.

The same AP story estimates that 28,000 acres (about 11,300 hectares) of coca are planted in Colombia’s fragile nature preserves, where aerial spraying continues to be forbidden. That is a small fraction of all coca estimated to have been grown in Colombia in 2004: either one-seventh of what the UN estimated (198,000 acres / 80,000 hectares) or one-tenth of what the United States estimated (282,000 acres / 114,000 hectares).

But coca cultivation, pushed by fumigation elsewhere, is increasing in Colombia’s parks, causing Bush and Uribe administration officials to increase their calls for an end to the ban on spraying in parks. They argue that the damage wrought by the cocaine industry (deforestation, chemicals for processing the drugs) is greater than any damage the glyphosate-based spray mixture would cause.

That would be true if the spraying’s immediate chemical effects were the only impact it made on the environment. But it is not, and environmentalists opposing spraying in parks do not need to fund expensive studies to determine the impact of glyphosate on rainforest soils, water and species.

In fact, the worst environmental impact of fumigation is not the glyphosate mixture itself (though Roundup is far from benign, especially where standing water is concerned). The worst damage is done when fumigation encourages growers to plant more coca than they did before.

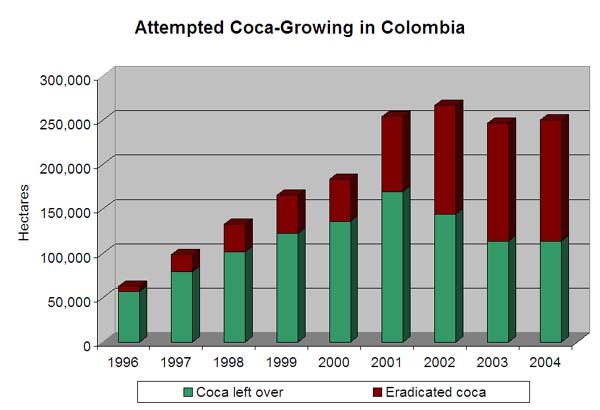

Nine years of steadily increasing spraying in Colombia has made brutally, abundantly clear that forced eradication, when not combined with alternative development, does not discourage people from growing coca. This seems obvious when coca is the most reliably profitable crop in remote, conflictive, neglected zones of the country. But the numbers bear it out.

- The UN Office of Drugs and Crime, in its June 2005 Colombia Coca Cultivation Survey [PDF format], reported the remarkable statistic that 62 percent of the coca fields its satellites detected in 2004 weren’t there in 2003. The majority of coca plantings were brand new. Campesinos, undiscouraged by the spraying, were planting the crop in new places.

- The State Department’s annual International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports tell us how much coca the Colombian government (with U.S. funds) eradicated each year, plus how much coca they estimate was left over afterward. Adding those two numbers together tells us roughly how much coca Colombian campesinos tried to plant each year. As fumigation has increased, the rate of “attempted coca-growing” has risen sharply.

|

| 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

| Coca left over | 57,200 | 79,500 | 101,800 | 122,500 | 136,200 | 169,800 | 144,400 | 113,850 | 114,000 |

| Eradicated coca | 5,600 | 19,000 | 31,123 | 43,246 | 47,371 | 84,251 | 122,695 | 132,817 | 136,555 |

| Total attempted coca-growing | 62,800 | 98,500 | 132,923 | 165,746 | 183,571 | 254,051 | 267,095 | 246,667 | 250,555 |

| Change, 2000-2004 | 36% |

|

| (All figures in hectares.) |

|

|

| ||

As more is sprayed, more is planted – 36 percent more just since Plan Colombia began in 2000. Much of these new plantings take place in areas that had not known coca before: pushed along by fumigation, growers are cutting down new forest and planting in new departments, new municipalities – and new nature reserves.

Given that experience, it’s not hard to imagine what will happen when fumigation is extended into Colombia’s parks. Growers will move deeper into the parks and other pristine areas and re-plant again. When the other option is to face deprivation – either in an urban slum or in depressed rural areas beyond the reach of government and economy – it almost seems rational for growers to try and profit from another few harvests before the spray planes find them again.

Fumigation pushed growers into Colombia’s national parks. If it is allowed to happen within the parks themselves, it will push growers deeper into these and other unspoiled areas.

What other option exists? The Colombian government, with U.S. support, can work on the ground.

This means manual eradication. The Colombian police claim to have eradicated 17,000 hectares of coca plants so far this year, employing 1,800 people. That’s 50 percent more coca than is believed to be in Colombia’s parks, so we know that the capacity to carry out this eradication exists. (Colombia’s park service could do much as well, if it were not so woefully underfunded.)

Of course, the main reason why the United States supports fumigation in Colombia and nowhere else is security, the danger that manual eradicators would be subject to guerrilla or paramilitary attack. But even if the Colombian government cannot control its territory despite years of military aid and investment, it should at least be able to control its parkland for the periods when eradication would take place. “It is said that there are places where manual eradication is difficult due to security,” writes El Tiempo columnist Daniel Samper. “Of course it is difficult. One elects governments to solve difficult problems with imagination and without inflicting social damage. To choose a deluge of poison is very easy, something that would occur to an above-average private.”

But working on the ground also means helping people who are so isolated and economically desperate that they have chosen to grow coca in national parks. Just like ex-combatants, just like displaced people, these individuals and families need their government’s help. Nearly all of them will voluntarily pull up their own coca plants if they could live with some semblance of law and order, with access to medicine and drinkable water, with a hope that their kids might be educated, in proximity to a road that led to places where people might buy their legal products, and with credit and assistance to help them produce and market those legal products. Most would welcome regular contact with civilians who represent their government.

Instead, though, U.S. policy does not aim to improve the Colombian government’s presence on the ground. By working from the air only, the fumigation strategy will do nothing but drive coca-growers deeper into Colombia’s parks.

Posted by isacson at September 29, 2005 09:05 PM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://ciponline.org/cgi-bin/mt-tb.cgi/142

Comments

Another excellent piece on the continuing problems that fumigation causes, even as it hopes to prevent them.

Fumigation is, as has been correctly pointed out, the (proportionally) cheap, easy and short term way out, but its eventual consequences are disastrous, for everybody involved.

A more comprehensive and long term initiative to address both drug supply and drug demand continues to be required.

Daniel Samper is right in that regard.

It would be more expensive and demand still greater sacrifices from the Colombian government and, logically, from the United States itself.

But that's what the people of both countries need, what they elected their respetive administrations for.

A new alternative has to be tried, instead of the same old prohibition and fumigation policies that are only band-aids...band-aids whose weak antibiotics only stimulate the virus to adapt and to spread further, without attacking its roots.

Posted by: jcg at September 30, 2005 04:39 PM

Ok, so there wasn't any decrease in the coca production over the past 2 years, but isn't the fall since the high in 2001 an improvement?

Posted by: luke at October 2, 2005 11:41 PM

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)