« The 2006 foreign aid outcome | Main | Drug Czar: fumigation opponents support narcoterrorists »

November 11, 2005

A conversation with the governor of Putumayo

Five years ago right now, Plan Colombia was just getting underway. Hundreds of millions of dollars of recently approved U.S. funds were being spent on helicopters, spray planes, and new military counter-narcotics units.

Plan Colombia’s main geographic focus at the time was the department of Putumayo, along the border with Ecuador and Peru. Putumayo was the largest producer of coca in Colombia in 1999-2000. It was also one of Colombia’s most violent departments, with frequent clashes between guerrillas and paramilitaries and untold numbers of civilians murdered. During the fall of 2000, the FARC declared an “armed stoppage” that halted the department’s road traffic for months.

The U.S.-funded response was to strengthen Colombian military and police units active in Putumayo, including two brand-new units: an Army Counter-Narcotics Brigade and a Navy Riverine Brigade. The police fumigation program expanded dramatically throughout Putumayo. And a smaller, though significant, amount of investment in alternative-development projects gradually began to flow into the zone.

Did the strategy work? Five years later, what has been the impact of this mostly military investment on conditions in Putumayo? Is the department safer? Has the drug trade subsided? Are alternative-development programs bringing prosperity?

The answer to all these questions is an emphatic no.

While on a visit to Bogotá last week, I had a chance to sit down with Carlos Palacios, the governor of Putumayo. Palacios now has one of the least desirable jobs on the planet: trying to govern and represent a department that remains overrun by illegal armed groups – all of whom have threatened his life. Because of the threats, Palacios – a former priest and community leader – never goes anywhere without several bodyguards.

“This has been the most violent year in memory in Putumayo,” Palacios said. “Open combat has been happening daily.” In 2005 so far, more soldiers have been killed in Putumayo than in any other department of Colombia. The FARC declared another “armed strike” that paralyzed the department in July and much of August. Yet another attack on power pylons left eight of Putumayo’s thirteen municipalities (counties) in the dark last week.

The hardest-hit municipality has been San Miguel, in Putumayo’s far southwest on the Ecuadorian border, whose county seat is La Dorada. As in much of Putumayo, San Miguel still has extensive coca cultivations, control of which is disputed between the FARC and the Liberators of the South paramilitary bloc (a unit of the Central Bolívar Bloc of the AUC, headed by “Javier Montáñez” or “Macaco,” who himself once worked as a coca buyer / middleman in Putumayo). The FARC tend to dominate rural San Miguel, and the paramilitaries dominate the few town centers. In La Dorada, an effort by local merchants earlier this year to protest the paramilitaries’ presence was met with a wave of threats and selective killings. The governor’s office has counted 87 armed-group attacks in this small municipality since the beginning of 2004 – nearly one per week.

The violence has increased this year for three reasons, said Palacios.

- The “Plan Patriota” military offensive taking place just to the north has displaced many guerrillas into Putumayo. This has been accompanied by an increase in FARC attacks and sabotage in Putumayo, in an effort to show that the guerrillas “are not defeated” and can still act at will.

- The proximity of the border has drawn armed groups to Putumayo; there are numerous clandestine routes into Ecuador through which drugs exit and arms enter. The FARC, Palacios said, have taken to launching attacks from the Ecuadorian side of the border; they have encampments and “practically a base of operations” in the northern Ecuadorian province of Sucumbíos.

- Strategically, Putumayo is still a very important zone. It borders Caquetá and Nariño, two key drug-crop producing areas. Several rivers in Putumayo are practically highways that lead to the Amazon basin, and control of river traffic is vital. Economically, Putumayo accounts for as much as 30 percent of Colombia’s potential oil reserves (though much of the oil is of a lower quality than that found to the northeast, in and around Arauca and Casanare).

The Colombian Army has moved 2,000 men into the department, but so far the violence has not subsided. Six official “early warnings” have been issued this year, but with no effective response. The Colombian Navy has a U.S.-funded Riverine Brigade, equipped with numerous well-armed boats, which has reduced FARC control of key rivers and riverside towns. However, Palacios notes, due to varying water levels, most rivers are navigable to the Navy’s boats only six months out of the year. During those six months, the rivers and nearby towns essentially return to FARC control.

Though Putumayo has been Colombia’s most fumigated department since Plan Colombia began, coca-growing persists and thrives in the department, governor Palacios warned. He estimated that there may be as much as 30,000 hectares of coca in Putumayo right now – far more than the United Nations’ 2004 satellite estimate of 4,386 hectares. The governor said that coca-growers are finding new ways to evade detection by satellites and aircraft – everything from very small plots, to new varieties that grow in shade, even to rumors of hydroponically-grown coca.

Governor Palacios opposes fumigation, which he sees as cruel and counterproductive. He points out that more than 16,000 hectares have been eradicated through alternative-development programs under the USAID-supported “early eradication” scheme, in which an entire community eradicates its coca in exchange for a package of projects and benefits.

However, Palacios says that he has been hearing more and more complaints about the “early eradication” aid. Communities, he says, were not asked what they would want to produce instead of coca, and instead had livelihoods assigned to them, such as raising pigs or growing fruit for a produce-concentrate processing plant in Orito municipality. Unfortunately, the pigs distributed with USAID funding mostly died of disease, as they were not well-suited to Putumayo’s climate and conditions. Of 152 pig-pens built throughout Putumayo, nearly all are now empty. The concentrates plant, which Palacios called “a white elephant,” is operating at a small fraction of capacity because it is offering very low prices to local growers.

Instead of dictating what people should produce, Palacios strongly suggests that USAID and its contractors do the following:

- Consult closely with communities in the elaboration of their own development and business plans.

- Make existing local organizations, particularly the juntas de acción comunal (elected “local action councils” that play an advisory role in governance), central actors in this process. This in turn will strengthen democracy, local participation and the social fabric.

- Provide generous credit instead of small grants. To the greatest extent possible, credits should be given to organizations, such as cooperatives, instead of individuals.

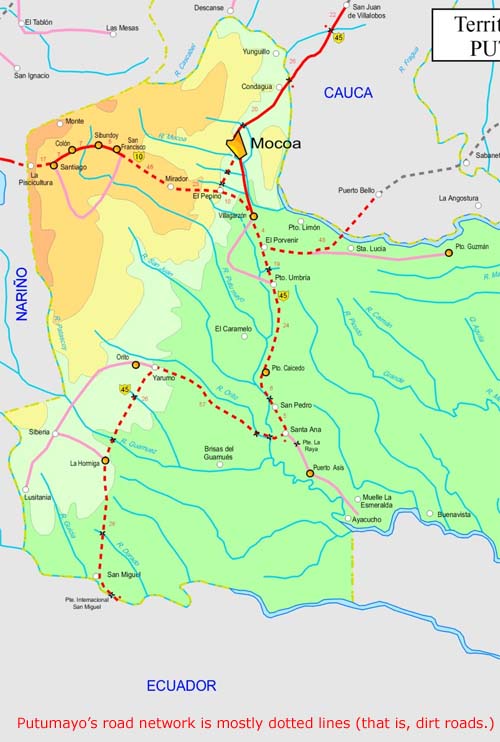

- Pave the department’s roads, which are in terrible shape if they exist at all. Putumayo’s roughly 200 kilometers of main road would cost about US$40 million to pave.

Governor Palacios has been seeking 30 billion pesos (about US$14 million) for an agricultural development plan for the department: a mix of credits and projects for goods that can get a decent price, particularly fish farming, small-scale family cattle breeding, and service jobs. But he has been unable to convince the U.S. or Bogotá governments to contribute.

Governor Palacios truly has one of the most frustrating jobs that one can have. It is worsened by the sad fact that, five years after beginning operations in Putumayo, Plan Colombia has done almost nothing to improve security, poverty and drug trafficking in the department. Halfway through his four-year term, Governor Carlos Palacios must deal with the disappointing aftermath. Still, we wish him the best of luck and look forward to talking to him again.

Posted by isacson at November 11, 2005 02:53 PM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://ciponline.org/cgi-bin/mt-tb.cgi/151

Comments

Interesting interview and analysis. I'd say that it's not so much that Plan Colombia and the rest have done nothing at all in Putumayo, but rather that they've only managed to keep things from getting substantially worse at most, without making enough of a dent to create substantial improvement. Without Plan Colombia and so on, Putumayo could be doing worse, but it's not really doing any better either. A mixed bag, in essence.

In other words, talking into consideration that it would be hard for things to stay truly static in practice, the situation seems to have been frozen at a minimum (and unsatisfying) level, instead of freezing it at a higher one.

Logically, the fact that Plan Colombia and everything else have failed to do much more than that evidences many of the previously mentioned problems, misconceptions, lack of resources, etc. that the Governor himself pointed out.

Still, perhaps for the purposes of a more comprehensive analysis, a year by year comparison that extended further back could be more useful to check out long term effects on the department, rather than one simply focusing on contrasting 2000 with 2005. Of course, that would mean focusing somewhat less on Plan Colombia per se and more on Putumayo.

Posted by: jcg at November 11, 2005 09:48 PM

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)