« Good ELN analysis | Main | A good congressman, forced to quit »

December 1, 2005

Backsliding on security?

During its first 2 ½ years or so in office, officials of Álvaro Uribe’s government – including the president, of course – defended their hard-line security policies with a barrage of statistics indicating a sharp decline in violence: fewer murders, fewer kidnappings, fewer guerrilla and paramilitary attacks on both civilian and military targets.

This year, however, the barrage of “good news” violence statistics has died down. Officials have not been reciting numbers as frequently, because the record has become troublingly mixed.

The news is not getting better. For some rather worrisome findings about the current direction of Colombia’s conflict, consult the latest report from a new Bogotá think-tank, the Conflict Analysis Resource Center (CERAC). Two of the group’s researchers – Jorge Restrepo of Colombia’s Javeriana University and Michael Spagat of the University of London – have led an effort to compile a violence database, which now has 21,000 entries through June 2005.

For a while, Restrepo’s and Spagat’s data had been corroborating government figures showing a rather miraculous across-the board drop in violence since Uribe took office in 2002, with civilians becoming much safer and the military recovering the initiative. Their newest report, though, appears to show a significant slowdown in the Colombian government’s momentum as of mid-2005.

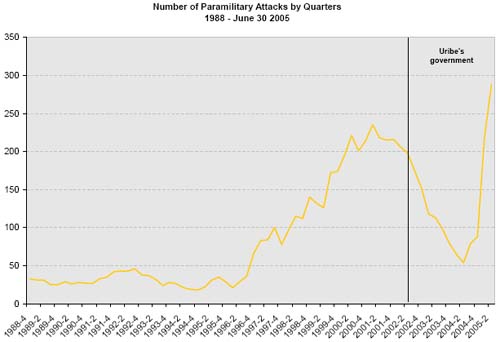

The most alarming finding is a very sharp rise in paramilitary attacks and killings in 2005, reversing the drop in paramilitary activity that followed the AUC’s declared cease-fire at the end of 2002. Just look at this graph:

The researchers find that the rise is not limited to groups that haven’t declared a cease-fire.

The takeoff in paramilitary activity is happening in many different places. We find a reactivation of paramilitary attacks and killings in 2005 in the Montes de María, in the south of Atlántico, in the east of Antioquia, in the west of Cundinamarca, in the Magdalena Medio region, in Meta, in Arauca and in the savannahs of Córdoba. This cannot be attributed to the few paramilitary groups that are not negotiating disarmament and demobilization with the government. On the contrary, this corresponds mostly with those areas where the negotiating groups are located.

Such a sharp rise in what are, in fact, cease-fire violations is more bad news for the AUC negotiation process, which is already becoming the closest thing Uribe has to a political Achilles’ heel as he launches his re-election campaign. (It will be interesting to see whether the highly questioned OAS verification mission documents a similar jump in paramilitary cease-fire violations.) The increase in paramilitary murders is not due to massacres; most of the incidents in the CERAC database are extrajudicial killings of one or two people at a time.

Led by the surge in paramilitary attacks, overall killings of civilians have increased sharply this year after declining during Uribe’s first two years. As a result, “civilian killings in the first half of 2005 are only about 10% below the rate in the last year before Uribe took power.”

The CERAC researchers note that “the guerrillas are not behind the increase in killings of civilians.” Disturbingly, they find that “there was an increase in government killings of civilians in the first half of 2005. This trend, although from a very low level, is worrisome, and the government needs to study in detail where these are occurring and why.”

A few other notable findings of the study (not even close to an exhaustive list – we again recommend visiting the CERAC site and looking over their findings):

- “The number of clashes between the government and the guerrillas is very high, although it has been falling from its peak of 2003.” However, there has been “a shift toward big-casualty events in 2005.”

- “The guerrillas are fighting less with the paramilitaries than they were a few years ago. In fact, the paramilitaries essentially ceased to be an anti-insurgent clashing force in the conflict beginning around 2002.”

- “This government has actually been fighting with the paramilitaries more than previous ones have.”

It’s hard to know what to conclude from these findings, some of which – especially the spike in paramilitary murders – are quite surprising. However, as we see the gains of 2002-2004 level off – or even begin to reverse – the new data may be showing us that Uribe’s “Democratic Security” policy, as implemented, may have reached its limits.

A strategy that so overwhelmingly favors the military dimension of governance, relying heavily on tactics like offensives, informants and roundups of suspects, can only achieve so much. Unless it begins to address the weakness of Colombia’s civilian government in conflictive zones, and to punish abuses when they occur, we may be seeing Democratic Security “hitting the wall,” reaching the extent of what it can do to decrease violence.

Quote of the week:

“In revolutionary processes like subversive warfare, there are always ‘self-eliminations.’ This doesn’t mean that one commits suicide, but that there are people in the rear who have particular ideological instructions to shoot their own comrades in the back, in order to exacerbate the population’s anger and to create a political rallying point.”

- Gen. Marcelo Antezana, the head of Bolivia’s army, arguing yesterday that most of the sixty people killed during October 2003 protests were murdered not by the security forces, but by fellow protesters seeking to turn people against the military.

Posted by isacson at December 1, 2005 11:47 PM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

Comments

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)