« "Swift-boating" the paramilitaries' critics | Main | Ciao, Michael Frühling »

January 28, 2006

Notes on a Senate staff trip to Colombia

Carl Meacham, a staffer for Sen. Richard Lugar (R-Indiana) on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, paid a visit to Bogotá on December 11-14. A moderate Republican (one of a disappearing breed), Sen. Lugar has been generally supportive of Plan Colombia. However, he has been one of the U.S. Congress’ chief critics of the paramilitary demobilization process. As the chairman of the committee, he plays an important role.

Meacham’s report (big PDF file) is a worthwhile read. I disagree with his analysis of Plan Patriota’s “success” and his recommendations for continued aid in its present form. I also wish he had taken the time to meet with representatives of Colombia’s human rights community and with other centrist analysts who hold a less sanguine view of Colombia’s security situation (such as CERAC and the Security and Democracy Foundation).

Nonetheless, the report differs strongly from the reigning view that everything is going wonderfully in Colombia. And it does contain some information that I hadn’t heard before, or at least hadn’t seen in writing before.

For example, the Colombian government has submitted a draft request for a five-year aid package to succeed Plan Colombia, from 2006-2010. The request was turned over to the State Department back on September 23, and the Uribe government calls it “Plan Colombia Consolidation Phase (PCCP).”

Though the U.S. Congress hasn’t been given a look at it yet, the draft document apparently includes four “pillars.”

The PCCP envisages four programmatic pillars that roughly correspond to the areas the USG supported through Plan Colombia (Pillars I-III), with the addition of the peace process (including demobilization and reintegration) as pillar IV. These pillars are:

- Fight Against Terrorism, Narcotics Trafficking, and International Organized Crime

- Strengthening Governmental Institutions and the Justice System

- Economics and Social Revitalization

- Process for Peace and Re-Integration

Meacham doesn’t recommend buying into the whole five-year “Plan Colombia II.” Instead, he recommends going one year at a time while keeping a close eye on Colombia and its neighbors.

In order to remain flexible, staff strongly recommends that USG [U.S. Government] support for Plan Colombia be extended on a year to year basis. … Policies toward the GOC [Government of Colombia] must be continually evaluated, given very fluid circumstances inside Colombia and its neighboring countries.

“Failure to address Congress’ concerns,” Meacham adds, “could weaken support for future extensions of Plan Colombia in the U.S. Congress.”

The report expresses disappointment in the lack of progress Plan Colombia has made against drugs and paramilitaries, given the size of U.S. investment.

The lack of reliable evidence of well-documented progress in the war against drugs and neutralizing paramilitaries is disappointing considering the billions of dollars the U.S. Congress has appropriated to finance drug interdiction and eradication since 2000.

Meacham sees a lack of consensus on whether drug supplies have been affected at all by Plan Colombia. While the Drug Czar’s office is claiming success, he notes, a recent report [PDF format] by the Congress’s independent Government Accountability Office casts doubt on the reliability of their measurements.

[S]ome Colombian officials have cautioned that while the statistics presented by the UN and White House are encouraging, more time is needed to determine if current efforts will yield real progress. They refer, for instance, to the impact of possible drug warehousing in Venezuela and Mexico on price and supply. However, given the absence of a consensus from respected organizations on the success of Plan Colombia in stemming the flow of cocaine to the United States, this does not bode well for efforts to push for its extension, at least at its current funding levels, without policy changes.

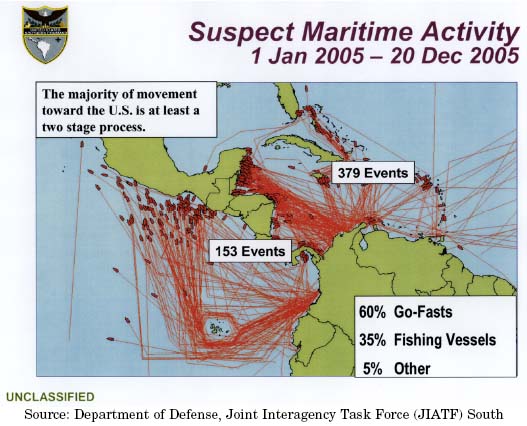

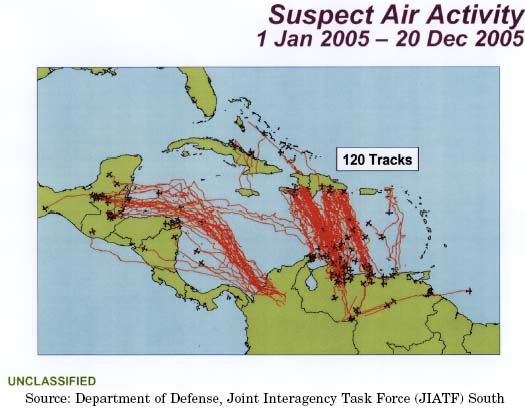

The report includes the following two maps, produced by the Southern Command’s Joint Interagency Task Force in Key West. The first shows the paths of suspected drug-smuggling boats detected during 2005. The second shows the paths of suspected drug-smuggling aircraft detected during 2005.

While the first shows most boats leaving Colombia, the second, surprisingly, shows most planes leaving Venezuela. Also surprisingly, both show no boats and very few planes landing in Cuba – Castro’s island appears here as an impenetrable barrier blocking drug smugglers’ progress toward the United States.

The report makes clear that Sen. Lugar continues to maintain a critical posture toward the paramilitary negotiations and demobilization. It notes that “the Uribe administration’s own study on demobilization, prepared two years ago, concluded that paramilitaries are responsible for at least 40 percent of the cocaine trafficking in Colombia.”

It makes clear that Colombia’s so-called “Justice and Peace Law,” passed in mid-2005 to govern paramilitary demobilizations, is inadequate and will allow paramilitary leaders to continue to enjoy great power as mafia-style bosses.

Staff’s opinion is that the law will be ineffective because it relies on the AUC’s willingness to co-operate in the implementation of its own demise. In addition the GOC has not built a strong framework for the law’s implementation. … Under the law there is a very real possibility that Commanders convicted of atrocities will receive very short sentences, even if it becomes clear that they have lied to prosecutors, kept most of their illegal assets, drug labs and wealth, or continued to engage in illegal paramilitary activity after they have ‘‘demobilized.’’ When these leaders re-enter society, their wealth, political power, and criminal networks will have remained intact, allowing them to replace their weapons and troops with ease if they choose, or form their own laundered and ‘‘legitimate’’ narco-gangs.

Meacham also worries that the “Justice and Peace Law” will make it impossible to extradite paramilitary drug traffickers to the United States.

[O]f particular concern to the United States under the new ‘‘Peace and Justice Law’’ is its ambiguity regarding the extradition of paramilitary commanders who have been indicted in the United States. It appears they can escape extradition by serving reduced sentences for their crimes in Colombia and then claim double jeopardy.

The committee report recommends that strong conditions be applied to any future aid for the paramilitary demobilization process.

The report expresses a surprising level of optimism about the progress of “Plan Patriota,” the Uribe government’s mostly military effort to re-take guerrilla-held territory with tens of thousands of troops and much U.S. aid. It reproduces a series of statistics about the offensive’s results (guerrillas killed, arms recovered, FARC encampments found) that the State Department has obtained from Colombia’s Defense Ministry.

According to the report, “The Colombian military claims that Plan Patriota has reduced the FARC ranks from 18,000 to 12,000 in the past year.” The past year? In September 2004 – fifteen months before Meacham’s visit – Gen. Carlos Ospina, the head of Colombia’s armed forces, cited the same statistic to me in answer to a question at a Georgetown University conference.

The report does include some new information (new to me at least) about “Plan Patriota.” For instance, a third phase of the military offensive (technically, a “Phase 2C”) is soon to be launched in Colombia’s populous department of Antioquia, whose capital is Medellín.

Plan Patriota, the GOC’s military campaign to extend government control and security presence throughout the national territory, is composed of two major phases: Phase 1, the planning and preparation for the forceful removal of armed groups; and Phase 2, which was divided into three components: 2A, 2B, and 2C, to implement Phase 2. Phase 2A, which took place from June to December 2003, resulted in the removal of the FARC from Bogotá and Cundinamarca Department. Phase 2B, which began in February 2004 and continues, includes Meta, Caqueta, and Guaviare Departments, involved the removal of the FARC from those areas. This is a large part of the area that comprised the “despeje,” or the area President Pastrana had conceded to the FARC. Phase 2C, which is the forceful removal of FARC from Antioquia Department, was scheduled to begin late in 2005, but has been postponed.

CIP has frequently criticized “Plan Patriota” for relying so heavily on military force, failing to address neglected regions’ extreme poverty or to establish a presence of the rest of the government. Meacham’s report discusses efforts so far to address non-military needs in the “Plan Patriota” zone through a so-called “Center for Coordinated Integral Action,” a military-led plan to bring in social services and civilian government institutions.

In addition, with support from the U.S. Military Group (MILGRP), the Colombia Government formed an interagency center to facilitate social services in seven areas that have traditionally suffered from little state presence and pressure from illegal armed groups. The “Center for Coordinated Integral Action” focuses on providing immediate social services, including documentation and medical clinics, and establishing longer term projects, such as economic reactivation. Approximately 40,000 individuals have been enrolled in state health care, judges, investigators, and public defenders have been placed in all 16 municipalities of the Plan Patriota area, and a public library was recently opened in the town of San Vicente del Caguan.

With the “Center for Coordinated Integral Action,” the planners of “Plan Patriota” at least acknowledge the need for non-military investment in the “re-taken” zone. But Meacham’s report does not give us a sense of the effort’s scale. Where statistics are elsewhere in evidence, we don’t know how many medical clinics or documentation projects have been established, much less how many exist outside of the “Plan Patriota” zone’s largest towns. Enrolling 40,000 individuals in health care is important, but over 1 million people live in the “Plan Patriota” zone, and there is a difference between enrolling people in the system and actually providing doctors, hospitals, medicines and access to care.

Meanwhile, a public library in San Vicente is great, but it really only benefits the people who live very close to the town center. I’ve been to San Vicente and can attest that the surrounding roads are so lunar-surface poor that those who live even 15 miles from the town would have to drive for an hour, in a four-wheel-drive vehicle, just to take out a book.

Posted by isacson at January 28, 2006 11:05 AM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://ciponline.org/cgi-bin/mt-tb.cgi/186

Comments

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)