« Military aid to Bolivia | Main | In their own words »

February 14, 2006

Manual eradication in parks: set up to fail?

Years of U.S.-supported aerial herbicide fumigation have caused thousands of Colombian coca-growing peasants, presented with no viable legal alternatives, to plant coca in Colombia’s national park system. More than 10,000 hectares of coca are now planted in national parks, out of approximately 80,000-115,000 hectares planted nationwide. While fumigation is currently prohibited in parks, Colombians have been debating whether to expand the spraying of “Round-Up” into these natural reserves.

Those who are horrified by this idea cite the potential damage that the glyphosate-based herbicide could do to fragile ecosystems. They point out that fumigation elsewhere has caused a huge increase in “attempted” coca-growing – the area sprayed plus the area left over – which means that hundreds of thousands of additional acres of forest, much of it in parks, could disappear.

On the other side of the debate is the U.S. government, which spends nearly $200 million each year on the spray program (the cost of contractor pilots and mechanics, plane maintenance, herbicides, and protection provided by Colombian national police and army anti-narcotics units), and doesn’t want to see any Colombian territory declared off-limits to spraying. Most officials in the Uribe government want to spray the parks, though those in charge of environmental protection are objecting. Colombian environmental experts and activists, as well as several influential columnists in the national media (most notably El Tiempo pundit Daniel Samper) have vocally opposed any Roundup in the parks.

Opponents of fumigation insist on manual eradication – sending in people to pull the plants out of the ground, as is done in Peru and Bolivia. This is slower and more dangerous than spraying from overhead. On the other hand, it doesn’t involve chemicals, it actually removes the plants for good, and – if done right – it puts the government on the ground, in contact with forgotten, isolated segments of a population that it’s supposed to be governing.

In 2005, the Colombian government dramatically expanded manual eradication in Colombia; the president’s “Advisor for Social Action” (which is also in charge of alternative development and aid to the displaced) deployed nearly 2,000 eradicators who pulled up more than 31,000 hectares of coca. (A hectare is 2.5 acres.) This was nearly triple the 11,000 hectares manually eradicated the year before. Meanwhile, nearly 140,000 more hectares were sprayed last year.

Most of this manual eradication went on without incident. This changed on December 28, when FARC guerrillas killed twenty-nine Colombian soldiers guarding the perimeter while eradicators destroyed coca in the Macarena National Park.

|

|

|

(Photos from El Tiempo; maps from www.invias.gov.co) |

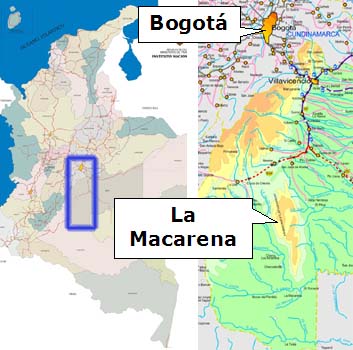

By all accounts Macarena, in western Meta department, is a strikingly beautiful place, a standalone ridge of mountains in the middle of otherwise flat jungle. Though it is only about 170 miles south of (and a very long day’s drive from) Bogotá, it is a park that few Colombians have seen. La Macarena and its environs have long been a FARC stronghold. It was part of the despeje zone that President Andrés Pastrana temporarily ceded to the guerrillas so that peace talks could take place. Today, La Macarena is a key battleground in “Plan Patriota,” the Colombian government’s two-year-old, U.S.-backed military offensive to “re-take” the FARC’s longtime jungle rearguard.

Two years into Plan Patriota, however, El Tiempo estimates that between 500 and 700 guerrillas remain in La Macarena and its vicinity. The authorities contend that the park contains over 4,500 hectares of coca crops, scattered in innumerable small plots throughout a total area of 630,000 hectares.

President Uribe could have reacted to the FARC’s December 28 attack by halting the manual eradication effort in La Macarena and sending in the spray planes for their first use in a park. This would have been a politically unpopular step to take in the midst of a re-election campaign, however, and his opponents would have made much of it. Instead, Uribe ordered a manual-eradication offensive of unprecedented proportions.

Operation “Colombia Verde” (Green Colombia) was launched on January 20, with the participation of 930 hired coca-eradicators, protected by 1,500 police and some military elements, along with a huge logistical effort to keep everyone fed, sheltered and transported. President Uribe helicoptered into Macarena to launch the effort; he pulled up 40 coca plants himself in front of the cameras.

Sending 900 civilians into a FARC-controlled park is dangerous, even with police protection. But for President Uribe, it’s a win-win proposition. If the eradicators manage to destroy 4,500 hectares of coca, then they’ve disrupted an income stream for the FARC and shown that the government can stop illegal coca-growing in parks. On the other hand, if they fail in the face of guerrilla violence and logistical snafus, then Uribe can cite this experience as proof that fumigation is the only answer for the national parks. The U.S. government – which has indicated no enthusiasm for Operation “Colombia Verde” – would likely be pleased with the latter outcome.

If the goal were to prove that manual eradication in parks can work, then one would have expected to see an all-out security effort, ensuring that eradicators could do their job without risk of exposure to guerrilla attack. We have not seen such an effort. While the deployment of up to 1,500 police agents is a good step, there has been much less involvement from the army, which is in fact trained to confront guerrillas, and already has a strong presence in the Plan Patriota zone.

In particular, why did Operation “Colombia Verde” begin without protection from elements of the Colombian Army’s 2,300-man Counter-Narcotics Brigade, which was created at much U.S. government expense when Plan Colombia began in 2000? An elite mobile unit with three battalions and access to lots of helicopters, the Brigade’s original purpose, in the words of Clinton administration State Department official Thomas Pickering, was to “accompany and back up police eradication and interdiction efforts” and to “provide secure conditions for the implementation of aid programs, including alternative development and relocation assistance.”

One of the Counter-Narcotics Brigade’s most basic purposes is to create security conditions for eradication. Normally, this unit coordinates closely with the fumigation program, ensuring that there are fewer guerrillas or paramilitaries on the ground to shoot at the spray planes. (When the brigade has failed to coordinate well with the spray program, as in the Catatumbo region in 2003, planes have been shot down.) Improving security conditions for Operation “Colombia Verde” appears to be an ideal mission for the Counter-Narcotics Brigade. Why, after spending so much money on this Brigade (with so few results from fumigation), was it not sent immediately to La Macarena? Did the U.S. government object, perhaps?

With insufficient security, this operation in the FARC’s backyard has run up against fierce guerrilla resistance. In its first two weeks, security forces faced eight guerrilla attacks. Six police were killed in a firefight on February 6. Three soldiers were killed by a roadside bomb on February 8. The eradicators must work with extreme caution, since the fields are planted not just with coca, but with land mines. The FARC have further complicated efforts by declaring an “armed stoppage,” prohibiting road traffic, throughout the nearby municipality (county) of Macarena.

The number of eradicators in the zone has dropped rapidly, from 930 at the beginning to only about 310 today. Fear of guerrilla attack is one reason, but the Colombian media have also reported extensively on the workers’ complaints about poor conditions. They cannot listen to radios or smoke at night, in order to avoid revealing their positions to guerrillas. They have faced chronic shortages of food and other supplies. Payments have been delivered very late, if at all.

The eradication operation is hanging by a thread. Nearly a month after its start, only 400 hectares of coca, less than 10 percent of the total, have been pulled up. The operation’s timeframe has been extended from 3 to 6 months. President Uribe is now promising housing subsidies for those eradicators who stick it out.

This experience so far raises many questions. Here are five:

1. Was the Macarena eradication project programmed to fail, in order to provide a rationale for fumigation in parks? “I suspect that the program is a smokescreen to justify herbicide fumigation,” a “local official” in Macarena said to the Associated Press last week. Indeed, the inadequacy of the security provided – especially the absence of the Counter-Narcotics Brigade – arouses suspicions that not all has been done to ensure the operation’s success.

On the other hand, this operation has received a lot of high-profile support from President Uribe, and if it fails due to poor execution it might reflect badly on him, in the middle of an election campaign. It’s also possible that the Uribe government – believing that Plan Patriota has hit the guerrillas harder than it has – simply underestimated the security risk in the zone.

2. Does the FARC prefer that the Colombian government spray? Spraying often has only a short-term impact on coca cultivation. Colombian Counter-Narcotics Police chief Col. Henry Gamboa recently told Cali’s El País, “What happens is that each hectare of coca has a productive potential of four harvests per year [some say up to six]. That is, when we spray we are only eliminating one harvest.” Manual eradication, on the other hand, is permanent: it removes the coca plants completely, and the growers must start over with seedlings. Manual eradication may be slow and labor-intensive, but it likely does much more to disrupt the FARC’s income stream.

Plus, unlike fumigation, manual eradication involves a long-term presence of government security forces (and, hopefully, civilian government representatives) on the ground. The government is placed in contact with population – often for the first time – in a previously abandoned zone that the guerrillas have become accustomed to controlling.

For these reasons, manual eradication may in fact hurt the guerrillas much more than fumigation. By responding aggressively to Operation “Colombia Verde” and perhaps inviting fumigation in the park, then, the FARC could be acting very much in its own interest.

3. Is the U.S. Government – which wants badly to fumigate everywhere – quietly opposed to Uribe’s manual eradication offensive in La Macarena? It could be that U.S. support is simply invisible, but there have been no celebratory announcements from the U.S. embassy, and no sign of U.S. officials accompanying President Uribe on his trips to the zone. Is Colombia on its own here? Has the U.S. embassy decided not to lend Operation “Colombia Verde” its resources and logistical expertise?

4. Won’t fumigation cause even more parkland to be destroyed for further coca-growing? Visit this page from the State Department’s last annual “International Narcotics Control Strategy Report.” Scroll down to the Colombia drug statistics table (or search for the words “Colombia Statistics”). Note that the amount of coca estimated in Colombia (“Potential Harvest”) has shrunk slightly from 122,500 hectares in 1999 to 113,850 in 2003 (it was 114,000 in 2004). However, note that the total amount of coca planted in Colombia (“Estimated Cultivation”) has exploded, from 167,746 hectares in 1999 to 246,667 hectares in 2003 (and a similar amount in 2004). That’s a four-year increase in “attempted” coca growing of 47 percent!

The conclusion is that vastly increased fumigation is not dissuading Colombia’s economically desperate coca-growers. Instead, it’s leading them to grow more coca. This means they are cutting down more forest, moving into new areas, and polluting more ecosystems. If eradication fails to come with economic alternatives – and if the Colombian government still cannot control its nature reserves – won’t coca growers, following the same pattern, simply respond by destroying more parkland?

5. Most importantly, what about the approximately 11,000 impoverished human beings who live in the Macarena park? The conditions of the park’s colonos are an old problem, as columnist and author Alfredo Molano wrote in last Sunday’s El Espectador. “Twenty-five years go, the colonos of La Macarena marched to San José del Guaviare to demand an effective and permanent solution to their problems: land titles, credit, roads, health, access to markets. The government responded that as long as they occupied land inside the park, there would be no aid at all. Some protesters were wounded, and several were murdered afterward. There was no solution.”

Only a very desperate person would move himself and his family into a remote, guerrilla-controlled park, to grow or pick coca in primitive, off-the-grid conditions, often to be paid only in guerrilla scrip instead of real currency. A government that actually intended to govern areas like La Macarena – to truly wrest them from guerrilla control – would recognize this desperation and help those who live there to establish themselves in the legal economy.

That is not happening. While some wish to spray these people from overhead, never to be in contact with them at all, the reigning policy is to send teams of eradicators, accompanied by security forces, to destroy their illegal crops. No effort is being made to make these people true citizens of Colombia; in fact, the majority are abandoning the zone for economic or security reasons, adding themselves once again to Colombia’s population of over three million internally displaced people.

If the current plan seeks merely to forcibly eradicate and displace people – whether by coca-pullers or by spray planes – without asserting a real state presence or providing the most basic of services, it will fail miserably. There will still be plenty of coca in La Macarena a year for now. And there will still be plenty of guerrillas, too. As Cambio magazine columnist María Elvira Samper notes, “It is a temporary operation, and as a result the most likely outcome is that, once the coca is eradicated, the situation will go back to what it always was: the state absent and the FARC present.”

Posted by isacson at February 14, 2006 2:24 PM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://ciponline.org/cgi-bin/mt-tb.cgi/193

Comments

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)