« Sen. Grassley takes on the drug czar | Main | Notes from Costa Rica »

May 4, 2006

Will nationalizing gas mean more money for Bolivia?

This is not the website to visit for research and analysis of energy-sector economics. Neither I nor anyone else here at CIP is really qualified to comment on the economic impact of Evo Morales' surprise nationalization of Bolivia's extensive gas reserves.

But why let a little thing like lack of expertise keep us from commenting anyway? (This is Washington, after all.) And this issue, which has been dominating the news from the region this week, is very much on our minds.

The headlines following the nationalization are certainly alarming.

- Watchdog warns of ‘dangerous’ trend on energy

- Some see Bolivia strategy backfiring

- Nationalisation fuels fears over Morales’ power

- Chávez casts long anti-American shadow

- Power grab is risky for Morales

- Bolivia's swoop for gas reserves stuns energy giants

- Bolivia's Energy Takeover: Populism Rules in the Andes

- Energy takeover puts Bolivia in a not-very exclusive club

- Outdated petulance

But let's leave aside for now the questions that the nationalizations raise about Bolivia's internal politics, its economic outlook, and its relations with its neighbors. Let's focus for a moment on the bottom line. Will nationalization increase the amount of money Bolivia gets from its gas reserves?

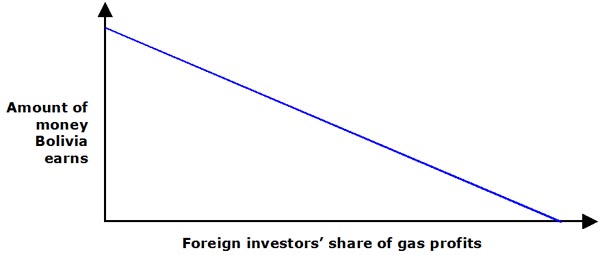

Clearly, the Bolivian government's answer is a resounding yes. Reduce or eliminate foreign companies' share of gas profits, and Bolivia gets to keep more of the pie. Their reasoning seems rather zero-sum: the less foreign companies get to keep, the more Bolivia gets. Show that as a graph and it would be a downward sloping line, like this.

But it's probably more complicated than that. After all, poor countries don't invite foreign oil and gas firms to their territory because their employees are especially charming or good-looking. These countries need foreign firms' capital, technology and expertise to help get the commodity out of the ground and to the market.

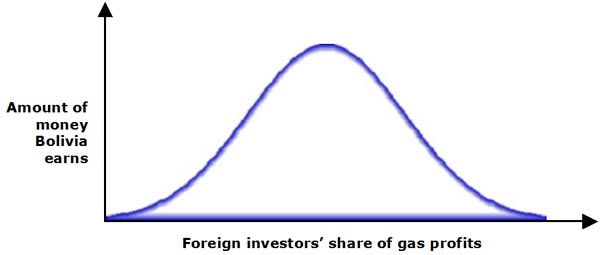

Take that into account, and it's not a zero-sum question at all. Instead of a downward-sloping line, the graph is probably more of a bell curve.

That is, if foreign companies see little of the profits, they won't invest enough to help Bolivia find gas, get it out of the ground, process it, and build pipelines to bring it to market. Bolivia's earnings will be low. However, if foreign companies succeed in getting too large a share of the revenue from gas, then the Bolivian people have been ripped off, and Bolivia's earnings will also be low.

For Bolivia, the trick is to avoid finding itself on either end of this bell curve. An effective hydrocarbons policy would place Bolivia right in the middle, where the nation gets a fair share of profits, but not so large a share as to discourage badly needed energy-sector investment. The goal should be a win-win arrangement in which Bolivia makes more money than it would otherwise, and foreign companies make a bit less but avoid inspiring the kind of resentments that lead to a backlash.

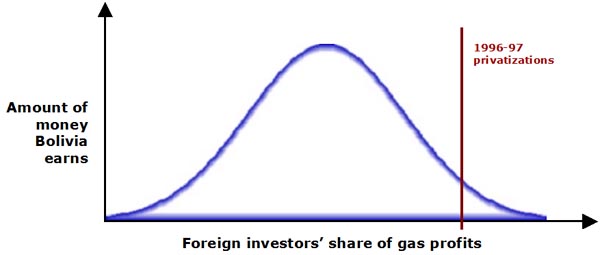

Most Bolivians clearly feel that the natural-gas privatizations of the mid-1990s, which allowed Bolivia to collect 18 percent of gas revenue as taxes, were too favorable to foreign firms, placing the country on the right edge of the bell curve.

Anger over this division of income fed protests that ultimately forced President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada to leave the country in October 2003. Evo Morales, meanwhile, was elected in part on his promise to nationalize the country's gas reserves.

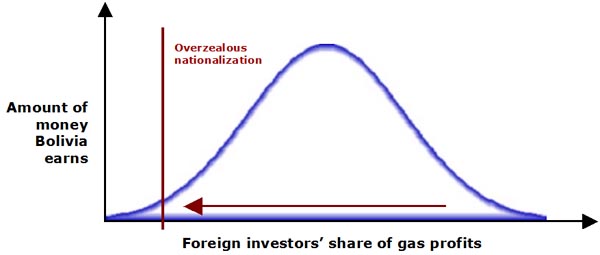

The question now is, will Morales' nationalization just push Bolivia to the other end of the bell curve, to the point where disinvestment keeps the country from getting enough of its gas reserves to market?

That depends, of course, on what sort of deal Bolivia negotiates with foreign firms over the next six months. It is entirely possible that this process, if well-managed, could bring Bolivia toward the "sweet spot" in the middle of the curve, greatly increasing government revenue. However, if a hard-line negotiating stance causes the foreign investors to vacate the country, the only thing that might keep Bolivia off the left edge of the curve would be assistance from Venezuela. And it's not certain whether even that would be enough.

Morales' surprise move on Monday is a very risky one. Without a strong dose of pragmatism as the nationalization process moves forward, it could end up being a costly move as well.

Posted by isacson at May 4, 2006 5:49 PM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://ciponline.org/cgi-bin/mt-tb.cgi/229

Comments

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)