« The Casa de Paz | Main | Sorry for the silence »

August 3, 2006

Notes from Medellín

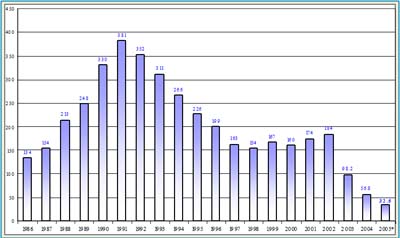

Last year, Medellín's murder rate totaled 37 killings for every 100,000 inhabitants. Suddenly this city - long considered one of the world's most violent - has come to suffer fewer homicides than U.S. cities like Washington (45), Detroit (42) and Baltimore (42). Medellín today is about as violent as Atlanta.

|

Medellín's dropping crime rate. |

Everyone I spoke with during my few days in the city - right, left and center - was thrilled with the change. Being able to walk the streets without fear of kidnappers, the disappearance of hitmen on motorcycles, and the ability to enter any neighborhood without aggression from territorial gangs have given residents a greater sense of civic pride and has won high approval ratings for both President Uribe and Medellín's jeans-wearing, left-of-center mayor, Sergio Fajardo.

People I interviewed were less in agreement, though, about why Medellín has become so much safer. Many credited President Uribe's tough security policies, which have brought a greater police and military presence in the vast, lawless slums that surround the city. Many said that Medellín is more peaceful because "the paramilitaries won" - the right-wing groups ejected guerrilla militias, dominate criminal activity in the city, and are presently on their best behavior as their demobilization and reintegration process proceeds. Many also gave credit to Medellín's city government, which has heavily invested its own resources in projects in poor neighborhoods and in programs to reintegrate demobilized paramilitaries.

As far as I could tell, all three hypotheses are correct. "Democratic Security," the paramilitaries' victory, and the mayor's office's programs combine into a series of factors - some encouraging, some very sinister - that explain Medellín's "renaissance." Here is a closer look.

1. Democratic Security. The Uribe government deserves credit for establishing a government presence - even if a largely military-police presence - in the poor barrios that ring Medellín. That presence simply didn't exist before.

Starting in the 1960s and 1970s, new arrivals to Medellín - many of them displaced by violence elsewhere - built their homes on the steep mountainsides that overlook the city to the east and west. What started out as squatter settlements and land invasions grew - often with the help of guerrilla groups - into labyrinthine warrens of handmade brick homes, steep stairways and pirated water and electricity. They kept growing, and today they make up at least half of Medellín's population of about 4 million.

It is hard to explain to a non-Colombian audience that even though these neighborhoods are easily visible from just about everywhere in central Medellín, they were, until very recently, just as completely ungoverned as far-flung, isolated zones like lower Putumayo or the Caguán river valley. Police and soldiers dared not enter them except in very large numbers, while most other central and municipal government agencies stayed away.

Residents grew accustomed to living under the control of street gangs made up largely of young people. Some were involved in organized crime and others (known as combos) were mainly territorial. In the absence of police, gangs carried out brutal "social cleansing" campaigns, ejecting or killing common criminals and other non-conformist elements.

Residents grew accustomed to living under the control of street gangs made up largely of young people. Some were involved in organized crime and others (known as combos) were mainly territorial. In the absence of police, gangs carried out brutal "social cleansing" campaigns, ejecting or killing common criminals and other non-conformist elements.

During the 1990s, the gang structure was taken over by guerrilla militias, who freely roamed neighborhoods carrying arms and wearing ski masks, spray-painting political slogans and holding indoctrination meetings. The militias too were mostly young people, including many minors. They also carried out social cleansing, and they facilitated rural guerrillas' supply and transit in and out of the city.

Starting around 2000, the AUC paramilitaries began to challenge the militias' domination of Medellín's slums. The paramilitaries' Metro Bloc, under the command of a man calling himself Rodrigo 00, and Cacique Nutibara Bloc (BCN), under the command of longtime drug-underworld figure Diego Fernando Murillo or "Don Berna," steadily increased their presence in the lawless barrios. The city's murder rate soared as the paramilitaries and militias waged ever more intense firefights in the neighborhoods' streets. Hundreds of civilians were caught in the crossfire, and many more were executed on suspicion of collaborating with the other side.

Wealthy with drug money and unchallenged by the security forces, Medellín's paramilitaries gained ground quickly. By mid-2002 they had ejected militias and taken over gangs in many neighborhoods. The guerrilla militias, however, continued to maintain strongholds in many neighborhoods, such as those in Comuna (Ward) 13 on the city's western fringe.

In May 2002, just as Colombians were about to hand Álvaro Uribe a first-round presidential election victory, the Colombian government made its first real foray into Comuna 13, a one-day military offensive called Operation Mariscal. A day of house-to-house urban warfare killed about a dozen civilians and failed to dislodge the militias.

Álvaro Uribe was in office for just over two months, in October 2002, when thousands of Colombia's military, police and judicial police launched Operation Orión in Comuna 13. The offensive went on for weeks - this time with a lower civilian death toll, but with over 400 people arrested, most of them later released for lack of evidence. After Operation Orión and a few other efforts in 2003, the guerrilla militias were gone from Medellín's neighborhoods.

At the same time, the soldiers and police who entered Comuna 13 and other neighborhoods stayed there. The Uribe government built police posts and increased the number of soldiers and officers assigned to Medellín. To date, there have been few complaints about the police's treatment of the population; responses to crime events have been relatively rapid and cases of abuse or corruption have been infrequent, though still rarely punished when they happen.

(This is not the case with the 4th Brigade, the Colombian Army unit responsible for Medellín and much of surrounding Antioquia department. The brigade is accused of killing dozens of civilians in the past two years, dressing their bodies in camouflage and presenting them as guerrillas killed in combat. Nearly all of these cases, though, have occurred outside of Medellín.)

(This is not the case with the 4th Brigade, the Colombian Army unit responsible for Medellín and much of surrounding Antioquia department. The brigade is accused of killing dozens of civilians in the past two years, dressing their bodies in camouflage and presenting them as guerrillas killed in combat. Nearly all of these cases, though, have occurred outside of Medellín.)

There is now at least some state presence in all of Medellín's neighborhoods, allowing Medellín to participate in a nationwide downturn in violence that has accompanied President Uribe's deployment of soldiers and police to population centers and main roads throughout the country.

2. The paramilitaries won. In many neighborhoods, however, state presence has not become state control. The paramilitaries were not ejected by Operation Orión and other military efforts; by some accounts they even assisted in the assault. Their presence in many neighborhoods remains strong. "Operation Orión was the beginning of the installation of a new power in Comuna 13, the same one that had ruled over other comunas in the city: that of the paramilitaries," wrote Ricardo Aricapa, the author of a 2005 book on Comuna 13, in a recent UNDP newsletter [PDF].

Following the guerrilla militias' expulsion, a period of fighting ensued throughout the city between the paramilitaries' Metro Bloc and Cacique Nutibara Bloc; by the end of 2003, Don Berna's BCN had won exclusive control. In a highly staged ceremony in November 2003, 868 members of the Nutibara Bloc turned in weapons; it would be the first of a long series of paramilitary demobilization ceremonies throughout Colombia over the next two and a half years.

Don Berna's men - some of them officially demobilized, some not - are a powerful force in Medellín today. They continue to control nearly all gang activity in Medellín's slums. Killings of opponents continue, though at a much lower level; use of knives or other instruments, instead of guns, is increasingly common. Young men in plainclothes can still be seen keeping quiet watch over many barrios, though they no longer install roadblocks or prevent outsiders from entering.

Don Berna's near-monopoly on criminal control of Medellín's neighborhoods is a major reason for the downturn in violence. Relative peace often results when a territory finds itself under a single group's uncontested dominion. The civilian population, tired of being caught in the crossfire, welcomes the change in its security, even if it is not quite the result of government control. It is a relief to have to pay extortion money to only one group, or to be free of threatened retribution for helping the "other side."

Don Berna's near-monopoly on criminal control of Medellín's neighborhoods is a major reason for the downturn in violence. Relative peace often results when a territory finds itself under a single group's uncontested dominion. The civilian population, tired of being caught in the crossfire, welcomes the change in its security, even if it is not quite the result of government control. It is a relief to have to pay extortion money to only one group, or to be free of threatened retribution for helping the "other side."

By several accounts, Don Berna has helped bring down violent crime rates by ordering his followers to desist from committing large-scale murder, displacement, and other harassment of the civilian population. The feared paramilitary leader is currently in the Itagüí prison south of Medellín, accused of ordering the killing of a state legislator last year. Nonetheless, he continues to maintain a strong "pyramidal structure" of control over the Cacique Nutibara Bloc muchachos, according to leaders I interviewed at the office of the Corporación Democracia, a non-governmental organization founded by ex-BCN paramilitary leaders.

The BCN leaders professed their continued loyalty to their "maximum leader, Adolfo Paz" (Don Berna's preferred nom de guerre), crediting him with having "humanized the war" and brought an end to the violence. "Adolfo Paz is the pacifier of Medellín," they assured me.

While acknowledging that Don Berna's order to behave has been a factor, Medellín city government officials insist that it is not the main factor. They recall that violence indicators have declined in much of the country, including many areas outside of Don Berna's influence."Don Berna does not control Medellín. He only controls criminality in Medellín," said the city's secretary of government, Alonso Salazar.

That is probably quite accurate. And Don Berna's consolidation of that control is an undeniable factor in Medellín's recent decline in criminality.

3. Medellín's city government is investing in peace. The Uribe government oversaw an increase in the security forces' presence and activities in Medellín and elsewhere in Colombia. It has done far less, however, to cement gains in security with investments in infrastructure, education, health, and other basic needs.

In Medellín, which has more resources than most municipalities, the local government has picked up much of the slack. The introduction of a police presence has been accompanied by investment in a "community policing" model focusing on improved response times, building community members' trust, and a less adversarial approach.

|

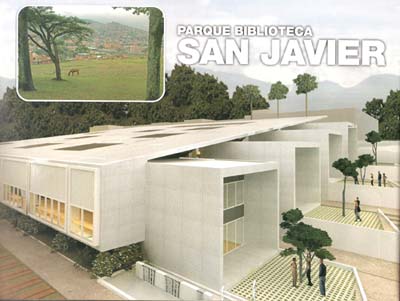

Rendering of a library under construction at the entrance to Comuna 13 in San Javier. |

The mayor's office has launched numerous infrastructure projects in the poor hillside barrios, building transportation, parks, libraries, museums and schools. In many cases, these buildings are not being constructed on the cheap: designed by architects, they stand out sharply from the ragged hollow-brick houses that surround them. Taking a page from former Bogotá mayor Antanas Mockus, Mayor Sergio Fajardo hopes that quality facilities, along with efforts to inspire a culture of citizenship, will encourage community members to take a more active role in maintaining tranquility and prosperity.

Where is the money coming from? Fajardo says that "tax collection in Medellín has increased by 20 percent since my administration began." He told me that he has broadened the tax base, convincing the business community and others to pay more through transparent management of the city's finances. "Nobody is going to call me 'Sergio 15,' someone who takes a 15 percent cut from every contract," he said. "We aren't stealing ... way too much money was stolen in the past."

Medellín needs a particularly full treasury because it has become a principal haven for former paramilitaries. Over 4,000 of the 30,000 who took part in collective demobilizations since 2003 now live in Medellín. The city government has spent much of its own money - about 23 billion pesos (US$10 million) so far - on attention to the demobilized population.

When the Cacique Nutibara Bloc demobilized in November 2003, many saw the process as a joke. 868 young men lined up before the cameras to turn in a smaller number of weapons. No law was in place for dealing with them. Many of those who demobilized, it was widely alleged, had no paramilitary past - they were gang members or common criminals who had been rounded up in the days or weeks before the ceremony. After a couple of weeks in an orientation center outside Medellín, those young men who did not have outstanding arrest warrants were returned to their own neighborhoods with vague promises of subsidies, education and job opportunities. Nothing was foreseen for their victims.

Colombia's national government distanced itself from the BCN demobilization; Peace Commissioner Luis Carlos Restrepo even called it an "embarrassment." The central government did not even offer a monthly stipend to the 868 ex-paramiliaries, though participants in all subsequent demobilizations are getting 400,000 pesos per month for eighteen months.

The Medellín city government made the best of it. Led by Secretary of Government Alonso Salazar, an expert in Medellín's urban violence, the mayor's office chose not to distinguish between "real" paramilitaries and gang members. There is simply no difference in too many cases, they argued, and the city government did not want to miss an opportunity to get troubled youth off the street and into the system.

The designers of the city's reintegration programs have clearly studied lessons learned from past cases. In addition to subsidies, former fighters are getting education and job training well beyond what the central government offers. "We found that, in most cases, a few months of education was not enough for them to get a real job," said Jorge Gaviria, who works on the city's reintegration effort. "They didn't speak well or present themselves right. They just weren't ready."

The city invested in psychological attention to the former fighters, including workshops in socialization and relationships with their communities. In some cases, this has included efforts at reconciliation with victims, including asking for forgiveness. Victims are also receiving increasing attention, as the city government has more recently launched a series of programs to provide psychological attention, offer employment assistance and "recover memory."

Can it last? Medellín's gains are remarkable. But since they depend on the current local government's policies and the goodwill of a feared criminal group, they may be fragile and easily reversible. Here are four factors that could put Medellín's recovery at risk.

- The transition from paramilitary domination to state control is far from complete, and it is unclear when it might be so. Though there is now a government presence in Medellín's barrios, the police alone do not appear to be enough to prevent the guerrillas from re-entering. At a July 24 security meeting, Mayor Fajardo repeated a longtime request that President Uribe send another 2,000 police to the city. This may not be forthcoming, and the ex-paramilitaries continue to play a de facto security role in too many neighborhoods. This is both unacceptable and unstable.

- Don Berna could be extradited. At any time, the DEA might discover new evidence that the "Pacifier of Medellín" is still conspiring to send drugs to the United States, in violation of the Justice and Peace law. This would bring renewed U.S. pressure to extradite him, which Colombia's government might find impossible to resist. Should "Don Berna" be put on a plane to Miami, his muchachos could revolt and re-arm, plunging the city into violence. Even if that outbreak of violence proves to be shortlived, the absence of a "maximum leader," combined with the absence of a sufficient state presence, could touch off a renewed power struggle for control of Medellín's organized crime and gang activity. Neighborhoods could once again become contested territory, and crime rates would rise.

- A future Medellín government might invest less in reintegration, attention to victims, and projects in poor neighborhoods. Mayor Fajardo's term ends at the end of next year. Mayors are not allowed to run for re-election in Colombia, and there is always a chance that Alonso Salazar, his likely successor, might not win (neither Fajardo nor Salazar, for example, is considered a supporter of President Uribe, who is quite popular in Medellín). Continuity of the city government's current programs, then, is never assured. However, even a civic-minded government could see its costly programs threatened by either an economic downturn or by the arrival of still more demobilized paramilitaries. Attracted by its generous reintegration efforts, which contrast sharply with what is available elsewhere, ex-paramilitaries are believed to be pouring into the city; the Corporación Democracia estimates that their numbers could grow from the current 4,000 to as much as 10,000 by the end of 2007. If that happens, the current system will not be able to sustain demand for its services.

- The national government's mismanagement could contribute to the reintegration effort's collapse - though this is an even greater risk outside Medellín. One of the most disturbing aspects of my visit to Medellín was that everyone I interviewed - from the local government to the ex-paramilitaries to non-governmental human rights advocates - was frustrated with the national government's handling of the paramilitary reintegration process. Every single interviewee cited the "lack of a national strategy" for dealing with the former fighters. The words "improvisation" and "neglect" were frequently invoked to describe Bogotá's approach to the challenge of helping more than 30,000 former combatants become citizens and participants in the legal economy. The central government has done little more than provide stipends and vocational training, leaving Medellín to fill in a lot of blanks.

The problem is even more serious and alarming beyond Medellín, where municipalities hosting former combatants are poorer, weakened by corruption, or simply unwilling to spend scarce resources on reintegration. In these cases, the lack of a more coherent central government strategy may bring disaster.

Posted by isacson at August 3, 2006 6:40 PM

Comments

Great, perceptive and thoughtful post as always, Adam. One minor quibble with this comment:

It is hard to explain to a non-Colombian audience that even though these neighborhoods are easily visible from just about everywhere in central Medellín, they were, until very recently, just as completely ungoverned as far-flung, isolated zones like lower Putumayo or the Caguán river valley. Police and soldiers dared not enter them except in very large numbers, while most other central and municipal government agencies stayed away.

It wouldn't be hard to explain that to someone in neighborhoods like Botafogo, Sao Conrado and or just about anywhere in the Zona Sul of Rio de Janeiro.

Posted by: Randy Paul at August 3, 2006 10:17 PM

Or Sao Paulo for that matter, good point. But it is still bizarre - I mean, Comuna 13 is a 20-minute taxi ride away from downtown if there's no traffic. I got no satisfactory answers for why the government stayed absent for so long. The closest I got was either "having it that way benefited powerful interests," or "for a long time, these people were viewed as squatters who had no right to be there, much less to demand services."

Posted by: Adam Isacson ![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/blog/nav-commenters.gif) at August 3, 2006 11:24 PM

at August 3, 2006 11:24 PM

Yes, thanks for the informative post, Adam. Medellín has changed since I lived there in the late 80's and listened to bombs go off from time to time.

The change shows that there is hope, not only for Medellín, but also for Colombia at large. Of course, there are so many countervailing negative trends that "disaster" is more likely than peace. But peace is possible. It's not preordained that Colombia suffer forever from inequality and violence. There is hope.

Posted by: richtiger ![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/blog/nav-commenters.gif) at August 4, 2006 12:55 AM

at August 4, 2006 12:55 AM

Adam,

That was a really super post, surely one of your best ever, extremely fair-minded and incisive at the same time.

I would like to add a couple of things. There is some supporting evidence for some of your ideas at http://www.cerac.org.co/pdf/UNDP_DDR_V2.pdf

(embarrassingly written by me but I think it’s relevant). It gives a time-series plot for the homicide rates in the Medellín-Antioquia area and compares it to the homicide rates in parts of the country that have seen no significant paramilitary activity in recent years, also marking off key dates. The picture makes it pretty clear that there has been a big reduction in the homicide rate connected to the demobilization of the BCN. It is unclear exactly why this has happened and whether it will persist for all of the reasons that you point to. The gains are fragile. But, as you also say, this cannot be just dismissed as a joke.

You say that the central government should help more with Medellín’s reintegration program which seems to be acting as a magnet of former and maybe not-so-former paramilitaries nationwide. Fair enough. But what about the international community? Things have changed somewhat but still there has been very little support, even for monitoring let along reintegration, during this critical period.

Mike Spagat

Posted by: Michael Spagat at August 4, 2006 10:39 AM

Thanks, Mike. I'm not as tough on the international community for one key reason. There's no foundation in the world that gives me money unless I submit a proposal for how I'd spend it, toward what objectives, according to what timetable, and how I'd measure success. The Colombian government has to do that too. Donor countries are already nervous about throwing money into a process that could go quite badly, or even - as some assert - usher in a "third generation" of paramilitaries. They would be much reassured by an indication that the government has thought this through in a comprehensive way and has a series of programs ready to put in place. But such a plan is sorely lacking.

Posted by: Adam Isacson ![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/blog/nav-commenters.gif) at August 4, 2006 5:43 PM

at August 4, 2006 5:43 PM

Adam, but what is similar to Rio is the closeness of the favelas to some of the richest neighborhoods in the country. Sao Conrado, one of Rio's richest neighborhoods is separated from Rocinha, the largest favela in Latin America, by a highway.

Posted by: Randy Paul ![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/blog/nav-commenters.gif) at August 5, 2006 12:30 PM

at August 5, 2006 12:30 PM

Post a comment

Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)