In early

September 2001, Congress was debating a number of national security

issues involving Latin America, including the Bush Administration's

new Andean counterdrug initiative and the continued U.S. military presence

on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques. While still critically important

in the region, both dropped to barely perceptible blips on Washington's

political radar screen after September 11th. While U.S. military programs

will continue in Latin America, they are likely to undergo some changes

as the United States responds to the terrorist attacks.

This

year's major assistance package to Latin America focuses on U.S. military

support for counternarcotics efforts in Colombia and the Andean region.

While major guerrilla groups operate in Colombia, the United States

has so far restricted its rationale for assistance to counter-drug support.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks, the already blurry line between

counternarcotics and counterinsurgency in Colombia may be erased.

This

year's major assistance package to Latin America focuses on U.S. military

support for counternarcotics efforts in Colombia and the Andean region.

While major guerrilla groups operate in Colombia, the United States

has so far restricted its rationale for assistance to counter-drug support.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks, the already blurry line between

counternarcotics and counterinsurgency in Colombia may be erased.

Human rights

conditions on aid are also at risk as U.S. attention turns to terrorist

threats. Efforts are underway to seek broad waiver authority to override

human rights safeguards on U.S. military programs worldwide. Agreements

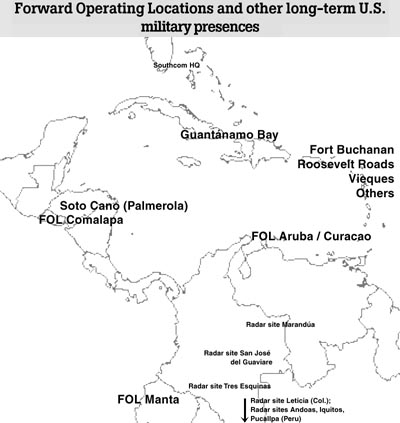

with countries hosting U.S. military Forward Operating Locations in

Latin America restrict their use to counterdrug activities, but there

may be pressure to use these facilities for counterterrorism purposes

as well.

Beyond

these potential changes, many of the programs the United States carries

out with Latin American militaries will not be dramatically affected

by recent events. Engagement is, and will continue to be, a primary

objective for many U.S. military programs in the region. The other overriding

rationale for U.S. military programs in this hemisphere has been counternarcotics,

and these programs will certainly remain high priorities.

Before

September 11, congressional oversight of U.S. military programs with

Latin America was limited, but steadily improving. Now, it is less likely

that Congress will focus significant attention on the oversight of any

programs outside of the terrorism response. While the shift in policymakers'

attention is understandable, U.S. involvement in the Colombian counterdrug

effort, the build up of the Forward Operating Locations and large scale

training programs will all continue. Military-to-military activities

and priorities will move forward, whether or not policymakers are minding

the store.

Increasing

Classification

Public

access to information about U.S. military assistance increased somewhat

since 1997, when the Latin America Working Group launched the "Just

the Facts" project. Congress required some new reports -- particularly

an overall accounting of U.S. military training and a description of

the Defense Department's counterdrug aid -- that gave much insight into

U.S.-Latin American military cooperation.

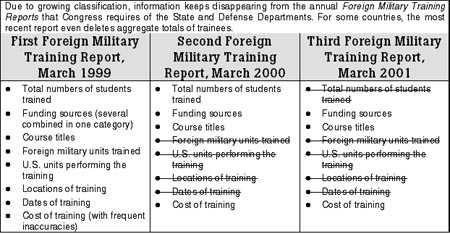

Since 2000,

however, we have seen a disturbing reversal in this progress. The above-mentioned

report on military training (known as the "Foreign Military Training

Report," or FMTR) was released in March 2000 with key information

from earlier reports classified. The 2000 FMTR would not identify the

foreign military units trained, making impossible monitoring of compliance

with human rights conditions in military-aid law. The report also removed

any mention of U.S. trainers and training locations, leaving the public

unable to determine which U.S. institutions (such as the former School

of the Americas) provide the most instruction and how much training

takes place overseas.

The

2001 FMTR increased classification still further, this time entirely

cutting out much of the counter-drug training provided by the Defense

Department -- one of the largest funding sources for military training

in Latin America. As a result, the report left out even aggregate numbers

of trainees for many Latin American countries. It became impossible

even to answer basic questions like "how many Bolivians were trained

in 2000," rendering the FMTR largely useless as an oversight tool.

The

2001 FMTR increased classification still further, this time entirely

cutting out much of the counter-drug training provided by the Defense

Department -- one of the largest funding sources for military training

in Latin America. As a result, the report left out even aggregate numbers

of trainees for many Latin American countries. It became impossible

even to answer basic questions like "how many Bolivians were trained

in 2000," rendering the FMTR largely useless as an oversight tool.

2001 also

saw another crucial tool severely weakened. All Latin America activities

were for the first time removed from unclassified distributions of the

Pentagon's annual report on Special Operations Forces' training with

foreign forces (known as the "Section 2011" report due to

its place in the U.S. Code). This report is the best source of information

about the Special Forces' Joint Combined Exchange Training (JCET) program.

JCET was a source of some controversy after 1998 press reports revealed

the program was active in Indonesia, a country banned at the time from

receiving military aid through the foreign assistance budget.

Congressional

committees considering 2002 legislation have called on the State and

Defense departments to reconsider increased classification. The Senate

Appropriations Committee's non-binding report accompanying the 2002

foreign aid bill expects the next FMTR "to contain the maximum

amount of information in declassified form, including information about

foreign units trained; the location of training; U.S. trainers' units;

course descriptions; the number of courses given and students trained;

and estimates for next-year training in each category of training reported."

The House version includes similar language.

Referring

to both the FMTR and the "Section 2011" report, the House

Armed Services Commmittee's report accompanying the 2002 Defense Authorization

bill notes that "information contained in these reports regarding

foreign military units trained is important and should, where appropriate,

be made available in an unclassified form to the general public."

2002

Legislation

Legislation

currently before the House of Representatives would make greater disclosure

of training into law. The "Foreign Military Training Responsibility

Act" (H.R. 1594) would also require a report on foreign police

training, improve tracking of trainees' careers, and establish a commission

to re-think the mission of foreign military training activities.

Other forces

in Congress are pushing in the opposite direction, seeking to weaken

further the Foreign Military Training Report. Section 816 of the House

of Representatives' version of the 2002-2003 Foreign Relations Authorization

Act (H.R. 1646) would require the FMTR to be produced only at the request

of congressional leaders, and only for specified countries.

The House

and Senate versions of the 2002 foreign aid bill continue reports, including

the FMTR, and human rights conditions that applied to previous aid,

while adding little new (other than those applying to Andean aid, discussed

below).

These conditions

include prohibitions on combat and technical training to Guatemala through

the International Military Education and Training (IMET) program. The

Senate Appropriations Committee's report on the 2002 foreign aid bill

notes that "the Committee is perplexed by the Administration's

requests for regular IMET assistance for some countries whose armed

forces have a recent history of actively undermining elected civilian

authorities, corruption, and human rights abuses, and which have shown

no commitment to reform."

The same

report includes language clarifying implementation of the Leahy Law,

which since 1997 has prohibited aid to foreign military units that violate

human rights with impunity. The subcommittee defines "unit"

as "the smallest operational group in the field that has been implicated

in the reported violation." The report also calls for the State

Department "to establish and maintain an electronic database of

credible evidence of gross violations of human rights by units of foreign

security forces. Each U.S. embassy should designate an appropriate official

to collect and submit data to the database from a wide range of sources

on a regular basis. Such a database would be one important depository

of evidence for making determinations regarding the implementation of

this provision." This clarification was needed because interpretation

and implementation of the law has varied even among U.S. embassies in

Latin America.

The

Andean Regional Initiative

The

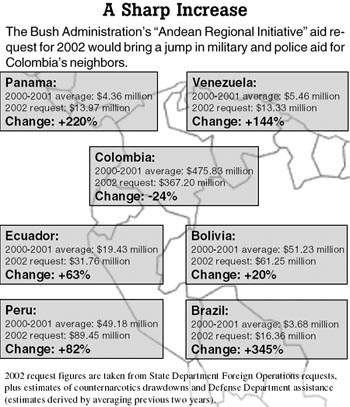

largest element of the United States' 2002 plans for the hemisphere

is continued support for "Plan Colombia," which began with

the July 2000 passage of a $1.3 billion package of "emergency"

anti-drug aid to Colombia and its neighbors. The Bush Administration's

"Andean Regional Initiative" aid request will continue programs

begun under the 2000 aid package, while greatly increasing military

and police assistance to six of Colombia's neighbors.

The

largest element of the United States' 2002 plans for the hemisphere

is continued support for "Plan Colombia," which began with

the July 2000 passage of a $1.3 billion package of "emergency"

anti-drug aid to Colombia and its neighbors. The Bush Administration's

"Andean Regional Initiative" aid request will continue programs

begun under the 2000 aid package, while greatly increasing military

and police assistance to six of Colombia's neighbors.

In dollar

terms, the request seeks less aid to Colombia's military and police

than Bogotá received in 2000 and 2001. This merely reflects that

the 2002 request includes no high-cost helicopters, which added about

$350 million to the 2000-2001 aid package.* The sixteen UH-60 Blackhawk

and roughly forty UH-1 Huey helicopters in that package began delivery

to Colombia in July 2001. They will provide mobility to a three-battalion

Counternarcotics Brigade in Colombia's army, created with heavy U.S.

assistance. The second and third battalions completed training by U.S.

Special Forces in December 2000 and May 2001, respectively.

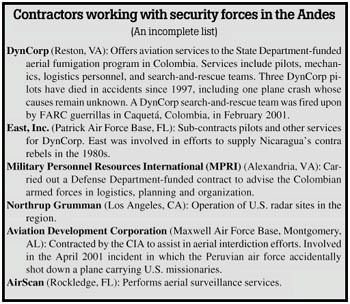

The battalions

are charged with guaranteeing security for an expanded program of aerial

fumigation of drug crops, carried out by Colombia's National Police

and U.S.-funded private contractors. The U.S. government contracts with

private companies, which employ civilians to work in Colombia as spray-plane

pilots, mechanics, search-and-rescue personnel, military trainers, logistics

experts and intelligence-gatherers, among other duties.

The

State Department reported in May 2001 that "the average number

of U.S. citizen civilian contractors working on State Department, USAID

and DOD programs supporting Plan Colombia on any given day has been

in the range of 160-180 persons." According to press reports, including

non-U.S. citizens increases this number to well over 300 civilian contractors.

The

State Department reported in May 2001 that "the average number

of U.S. citizen civilian contractors working on State Department, USAID

and DOD programs supporting Plan Colombia on any given day has been

in the range of 160-180 persons." According to press reports, including

non-U.S. citizens increases this number to well over 300 civilian contractors.

The heavy

use of contractors has been a source of some controversy, as it raises

issues of accountability and proximity to Colombia's conflict. The controversy

was fed by the involvement of contract personnel in the accidental shooting

down of a plane carrying U.S. missionaries, mistaken for drug traffickers,

over Peru in April 2001.

While

the Andean Regional Initiative will slightly decrease military and police

aid levels for Colombia in 2002, it will mean a large leap in this assistance

to Colombia's neigbors.

While

the Andean Regional Initiative will slightly decrease military and police

aid levels for Colombia in 2002, it will mean a large leap in this assistance

to Colombia's neigbors.

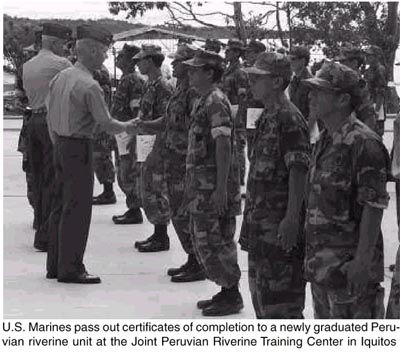

Peru's

armed forces will enter the post-Fujimori period with new U.S. funding

for Navy riverine efforts, Air Force C-26 sensor packages, engine upgrades,

and training. The Peruvian police will get upgrades to fourteen UH-1

Huey helicopters and greater assistance for manual coca eradication

programs.

Securing

Ecuador's border with Colombia will be the chief focus of U.S. security

assitance to Quito. Assistance to Ecuador's military and police will

include training, logistical support, communications gear and maintenance

of helicopters and equipment. The United States is also in the midst

of a $61.2 million upgrade to an airbase at Manta, on Ecuador's Pacific

Coast. U.S. aircraft will use Manta as a "Forward Operating Location"

to host and maintain surveillance flights over the drug "source

zone" (particularly southern Colombia, Peru and Bolivia).

The United

States has built barracks for Bolivia's Army in the Chapare coca-growing

region, and sent numerous teams of counter-drug military trainers. Plans

for 2002 include equipment, weapons and training for the ground, water

and air interdiction efforts of all branches of Bolivia's armed forces

and police.

Brazil's

police will receive significant counternarcotics assistance for the

first time in 2002. Much of it will support Brazil's "Operation

Cobra," a three-year effort to fortify the border with Colombia.

Securing

the Colombian border is a central goal of U.S. police assistance in

armyless Panama. Greatly increased aid will provide equipment, training

and advice to Panamanian National Police border units, National Maritime

Service, and National Air Service.

U.S.

military relations with the government of Venezuelan President Hugo

Chávez have been mixed. Venezuela continues to prohibit use of

its airspace by U.S. counter-drug surveillance aircraft, and the State

Department has criticized Venezuela's own interdiction efforts as "largely

unsuccessful." In August 2001, Venezuela revoked the fifty-year-old

agreement granting the U.S. Military Group a rent-free presence in the

Fuerte Tiuna military headquarters in Caracas. Venezuelan Defense Minister

José Vicente Rangel criticized the agreement as "a museum

piece of the Cold War." On the other hand, U.S. collaboration with

Venezuela's National Guard continues to be close, particularly on counter-narcotics

matters, and Venezuela's security forces will see a significant increase

in U.S. funding in 2002 as part of the Andean Regional Initiative.

U.S.

military relations with the government of Venezuelan President Hugo

Chávez have been mixed. Venezuela continues to prohibit use of

its airspace by U.S. counter-drug surveillance aircraft, and the State

Department has criticized Venezuela's own interdiction efforts as "largely

unsuccessful." In August 2001, Venezuela revoked the fifty-year-old

agreement granting the U.S. Military Group a rent-free presence in the

Fuerte Tiuna military headquarters in Caracas. Venezuelan Defense Minister

José Vicente Rangel criticized the agreement as "a museum

piece of the Cold War." On the other hand, U.S. collaboration with

Venezuela's National Guard continues to be close, particularly on counter-narcotics

matters, and Venezuela's security forces will see a significant increase

in U.S. funding in 2002 as part of the Andean Regional Initiative.

U.S. aid

to the Andes continues to receive more scrutiny than any other activity

in the hemisphere. Colombia is particularly controversial. Concerns

have centered on the human rights record of the world's third-largest

recipient of security assistance (as of publication) and the possibility

of entanglement in a broadening conflict. The Senate Appropriations

Committee noted that "many Members have expressed concerns that

this program is drawing the United States into a prolonged civil war

that may pose grave risks to American personnel and further hardships

for the Colombian people."

The executive

branch has long dismissed such concerns by insisting that U.S. aid is

for counternarcotics programs, not counter-insurgency. However, the

Bush Administration is carrying out a "formal review" to determine

whether the U.S. mission should remain "just narcotics, or is there

some wider stake we may have in the survival of a friendly democratic

government," as Assistant Secretary of Defense for International

Security Affairs Peter Rodman defined it in August 2001.

Uncertainty

about the direction of U.S. policy toward the Andes has led to the placement

of several restrictions and reporting requirements on the 2002 Andean

aid package, which as this document goes to press is currently before

Congress as part of the Foreign Operations appropriation. Both houses'

versions place human rights conditions on military assistance, and include

maximum numbers of U.S. military personnel and contractors allowed in

Colombia at any given time. The Senate's version would cut off aerial

fumigation funding until the government certifies the chemicals' safety

and use according to U.S. government and manufacturers' standards, and

until reparation mechanisms are in effect for those unjustly fumigated.

As this

document goes to press in late September 2001, it is unclear how U.S.

aid to the Andes will be affected by the September 11 terrorist attacks.

A direct threat to U.S. security on its own soil may divert attention

and resources -- including military aid -- away from the region. It

is at least as likely, though, that a new global "war" on

terrorism might ease a shift toward counter-insurgency assistance, with

the pretext of helping Colombia to control the three armed groups in

its country that appear on the State Department's list of thirty-one

international terrorist organizations.

Mexico

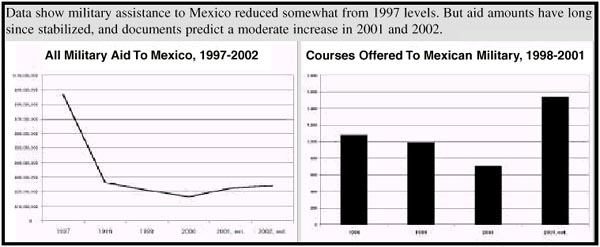

The

United States' relationship with Mexico's military continues to be based

on counternarcotics. In 2001, the United States plans to train 1,363

Mexican military personnel. While training numbers have fluctuated somewhat

over the past few years, the average remains around 1,000 per year.

The fluctuations likely have more to do with temporary political considerations

than with significant changes in priorities or direction.

The

United States' relationship with Mexico's military continues to be based

on counternarcotics. In 2001, the United States plans to train 1,363

Mexican military personnel. While training numbers have fluctuated somewhat

over the past few years, the average remains around 1,000 per year.

The fluctuations likely have more to do with temporary political considerations

than with significant changes in priorities or direction.

According

to the 2000-2001 Foreign Military Training Report, "The U.S. conducts

extensive training in the counter-narcotics area, with special focus

in helicopter repair and maintenance of aircraft. Technical assistance

covering a broad range of counter-drug capabilities and assets help

enhance Mexico's ability to combat narcotic traffickers and continue

its cooperation with U.S. counter-drug efforts."

Aircraft

training with Mexico began in earnest when the United States donated

73 used helicopters for counter-drug use in 1996 and 1997. Though Mexico

returned all of the helicopters in 1999, the training program has continued;

the Mexican military has obtained helicopters from other sources and

standard helicopter training applies equally to the new equipment.

While the

annual Foreign Military Training Report has classified information about

foreign units trained by the United States, it is clear that counternarcotics

work has taken on more of a maritime focus, and that the United States

is working closely with the "Marina" in Mexico.

This same

report appears to indicate an increase in training programs that take

place on Mexican soil. Unlike the rest of Latin America, where U.S.

mobile training teams and Special Operations Forces conduct much training

in host countries, most Mexican trainees have been brought to the United

States for training. The presence of U.S. troops in Mexican territory

has been historically controversial.

However,

this year's FMTR indicates that about half of expected trainees for

2001 are taking courses either given by mobile training teams or courses

often provided in that fashion.

While off

somewhat from 1996 and 1997, when the helicopters were transferred and

significant resources went to training counter-drug Air Mobile Special

Forces Groups (GAFEs), engagement with the Mexican military is still

a major priority for the United States. While Department of Defense

officials admit that the relationship has been rocky, one recently described

the periodic crises as "on the margins of the fundamental relationship."

Central

America

While

military and police aid levels to Central America lag behind the Andes

and Mexico, they are no longer declining from their 1980s highs.

While

military and police aid levels to Central America lag behind the Andes

and Mexico, they are no longer declining from their 1980s highs.

El Salvador's

security forces in particular are experiencing a significant jump in

U.S. aid. Aid in dollar terms, which stayed below $1 million since the

early 1990s, may reach nearly $4 million in 2002 thanks to a large infusion

of Foreign Military Financing (FMF, the U.S. government's main non-counternarcotics

military aid program). The State Department reports that the FMF will

help the Salvadoran military refurbish helicopters overused in response

to January 2001 earthquakes, and will support naval vessels used for

drug interdiction.

El Salvador

is also hosting a Forward Operating Location at its Comalapa airport,

where U.S. Navy and Customs personnel are supporting counter-drug surveillance

aircraft on missions over the eastern Pacific Ocean. While the site

is in limited use, improvements valued at $9.3 million will be made

in 2002 and 2003.

Counternarcotics

assistance to Central America is increasing, though peacekeeping and

humanitarian assistance continue to be key missions of U.S. military

cooperation with the region. The Southern Command's Humanitarian and

Civic Assistance (HCA) program, in which U.S. miltiary personnel pay

visits to build infrastructure and provide medical services, remains

more active in Central America than in the rest of the hemisphere. HCA

exercises operated at an unprecedented pace in the region in 1999 following

Hurricane Mitch; while they fell off somewhat in 2000, the program increased

again in 2001 following the El Salvador earthquakes.

Counternarcotics

assistance to Central America is increasing, though peacekeeping and

humanitarian assistance continue to be key missions of U.S. military

cooperation with the region. The Southern Command's Humanitarian and

Civic Assistance (HCA) program, in which U.S. miltiary personnel pay

visits to build infrastructure and provide medical services, remains

more active in Central America than in the rest of the hemisphere. HCA

exercises operated at an unprecedented pace in the region in 1999 following

Hurricane Mitch; while they fell off somewhat in 2000, the program increased

again in 2001 following the El Salvador earthquakes.

In Honduras,

the Southern Command's "Joint Task Force Bravo" continues

to operate out of the Soto Cano airbase near Comayagua. The unit's 550

U.S. military personnel and 650 U.S. and Honduran civilians provide

"responsive helicopter support to missions in Latin America and

the Caribbean," Southern Command chief Gen. Peter Pace explained

in April 2001.

Nicaragua

and Guatemala are two of the only countries in the hemisphere that do

not receive combat and technical training through the International

Military Education and Training (IMET) program. Both countries are limited

to "Expanded IMET," which offers courses in management, civil-military

relations, human rights and related topics. In the Nicaraguan case this

is a matter of policy, probably owing to the Nicaraguan army's Sandinista

origins. Guatemala, however, is prohibited by law from receiving military

aid through regular IMET and the FMF programs, due to persisting human

rights concerns. The House Appropriations Committee urges "renewed

emphasis on improving the Guatemalan civilian police force ... to strengthen

law enforcement and modernization of the state."

The

Caribbean

Anti-drug

aid is expected to fuel increased military and police assistance to

the Caribbean in 2001 and 2002, as the State Department's 2002 request

for its International Narcotics Control (INC) program foresees large

increases to the region.

Anti-drug

aid is expected to fuel increased military and police assistance to

the Caribbean in 2001 and 2002, as the State Department's 2002 request

for its International Narcotics Control (INC) program foresees large

increases to the region.

The Defense

Department is funding many construction improvements to the U.S. Forward

Operating Location on the islands of Aruba and Curacao in the Netherlands

Antilles. $10.2 million will build new runways and other facilities

for Aruba, which is used by U.S. Customs aircraft. Another $43.9 million

will support similar upgrades at Curacao, which hosts a larger number

of U.S. military planes. Construction will end in late 2002.

Rivaling

Plan Colombia for controversy in the region is the U.S. Navy's continued

use of a firing range (the Atlantic Fleet Weapons Training Facility)

on the island of Vieques off the eastern coast of Puerto Rico. The site

has been a focus of intense protest since April 1999, when a plane practicing

bombing missed its target, killing a Puerto Rican civilian security

guard. The Navy is currently practicing bombing on the site using inert

concrete bombs; a non-binding referendum of Vieques residents in July

2001 found that 68 percent wanted the Navy to vacate the sixty-year-old

site immediately.

The firing

range's future should be sealed by a binding referendum in November

2001 that does not include the Navy's immediate withdrawal as an option.

Voters will choose either to allow the Navy to remain (and receive $50

million in economic assistance) or to force the Navy to leave in 2003

(and receive no funds).

Language

in the House of Representatives' version of the 2002 Defense Authorization

bill would repeal this referendum and let the Navy decide whether it

wants to leave the Vieques site. As this report goes to press following

the September 11 terrorist attacks, policymakers are renewing calls

to continue using the Vieques range while the Navy lacks available alternate

sites.

Haiti,

which in the mid-1990s received a great deal of assistance to establish

a national police force, today receives little police aid (Haiti has

no army), due to prohibitions on assistance until "Haiti has held

free and fair elections to seat a new parliament." Foreign aid

legislation would allow aid for Haiti's Coast Guard; the Bush Administration's

2002 funding request to Congress asks for "resumption of FMF assistance

to the HNP [Haitian National Police], and its Coast Guard in particular,

mostly to enhance counternarcotics capabilities."

The Dominican

Republic will receive small amounts of FMF to support coastal patrol

boats for counter-drug and migrant operations, and to provide tactical

communications for military disaster-relief efforts.

The

Southern Cone

On

June 13, 2001 the Pentagon formally notified Congress of the forthcoming

sale of ten F-16 C/D series fighter planes and two KC-135 tanker aircraft

to Chile. The planes do not include sophisticated AMRAAM missiles, as

some had expected.

On

June 13, 2001 the Pentagon formally notified Congress of the forthcoming

sale of ten F-16 C/D series fighter planes and two KC-135 tanker aircraft

to Chile. The planes do not include sophisticated AMRAAM missiles, as

some had expected.

The roughly

$700 million sale is the first since a twenty-year-old policy banning

high-tech weapons sales to Latin America was lifted in 1997. (One exception

had been made in the early 1980s, when F-16s were sold to Venezuela.)

Purchases by Chile and, potentially, by its Southern Cone neighbors

have been slowed somewhat by the region's chronic economic crises.

The

New York Times reported in August that "Brasilia has set

aside $700 million to buy up to 24 supersonic fighters. But it is insisting

that any supplier provide advanced avionics and that Brazil's burgeoning

aerospace industry be allowed to make the planes here for itself."

The U.S. government may be uncomfortable with the level of technology

transfer that these conditions would demand.

The

New York Times reported in August that "Brasilia has set

aside $700 million to buy up to 24 supersonic fighters. But it is insisting

that any supplier provide advanced avionics and that Brazil's burgeoning

aerospace industry be allowed to make the planes here for itself."

The U.S. government may be uncomfortable with the level of technology

transfer that these conditions would demand.

Argentina,

in the midst of a deep recession, has not announced plans to buy aircraft.

Relations between the U.S. and Argentine armed forces are quite close,

however, as Argentina is the only Latin American country to hold the

largely symbolic status of "Major Non-NATO Ally" of the United

States. This status has given Argentina priority access to the United

States' program of giveaways of Excess Defense Articles (EDA). This

program has provided Argentina with tens of millions of dollars in weapons

and equipment over the past few years. The State Department's 2002 aid

request states that EDA and a rapidly increasing amount of grant FMF

assistance are aimed at strengthening the Argentine military's abiliy

to participate in international peacekeeping missions. "Receipt

of grant EDA helps Argentina obtain NATO-compatible equipment, such

as transport and communications equipment, which improves its interoperability

with NATO forces in peacekeeping operations."

Training

Though

the most recent Foreign Military Training Report classified data necessary

to make an exact determination, the launch of Plan Colombia and the

training of entire battalons almost assuredly increased the number of

Latin American military personnel trained in 2000 over the 12,923 reported

in 1999. If patterns revealed by previous FMTRs continued in 2000, the

majority of this training took place overseas, given by U.S. instructors

(mainly Special Forces units) in the students' own countries.

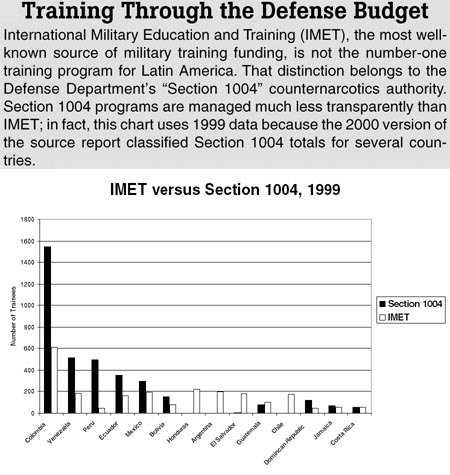

Though

most of the attention of congressional oversight staff remains fixed

on the standard foreign aid budget, the largest source of funding for

training in Latin America is in fact the $300 billion Defense Department

budget. Under an authorization normally referred to as "Section

1004," the Pentagon uses its counter-drug budget to train many

more individuals than does IMET, the largest training program in the

foreign aid budget.

Though

most of the attention of congressional oversight staff remains fixed

on the standard foreign aid budget, the largest source of funding for

training in Latin America is in fact the $300 billion Defense Department

budget. Under an authorization normally referred to as "Section

1004," the Pentagon uses its counter-drug budget to train many

more individuals than does IMET, the largest training program in the

foreign aid budget.

The

former School of the Americas

The best-known

symbol of military training for Latin America underwent a makeover in

late 2000 and early 2001. Following a change in the law proposed by

the Pentagon, the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation

(WHINSEC) now occupies the building that housed the U.S. Army School

of the Americas at Fort Benning, Georgia.

The school,

the only U.S. Army institution that offers training in Spanish, is in

the midst of reforming its curriculum and removing several combat courses;

the change in the law codifies several previously existing oversight

mechanisms, such as a Board of Visitors and regular reports on the school's

activities.

Though

its coursework is more intensive than that offered by most U.S. training

teams overseas, the WHINSEC accounts for only about 5 percent of all

Latin American military personnel trained by the United States.

Foreign

Military Financing

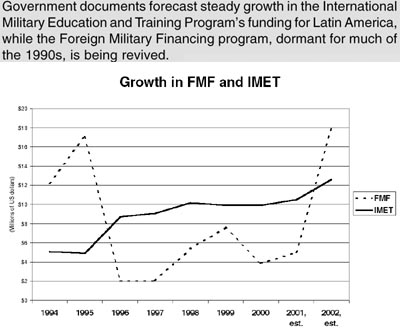

The

Bush Administration's aid request for 2002 would revive Foreign Military

Financing (FMF), a military aid program that had been used sparingly

in Latin America during the past ten years. Primarily intended to provide

military equipment for non-counternarcotics purposes, FMF levels in

the hemisphere are expected to rise from about $4 million in 2000 to

at least $18 million in 2002, with Argentina, Bolivia and El Salvador

the largest beneficiaries.

The

Bush Administration's aid request for 2002 would revive Foreign Military

Financing (FMF), a military aid program that had been used sparingly

in Latin America during the past ten years. Primarily intended to provide

military equipment for non-counternarcotics purposes, FMF levels in

the hemisphere are expected to rise from about $4 million in 2000 to

at least $18 million in 2002, with Argentina, Bolivia and El Salvador

the largest beneficiaries.

State Department

documents also indicate that Latin America will share in a large expected

worldwide increase in IMET funds for military training. The number of

IMET-funded trainees from Latin America would increase by about one-quarter

in two years, from 2,684 in 2000 to 3,399 in 2002.

Anti-Terrorism

Assistance

Latin America

has accounted for roughly ten percent of the worldwide budget of the

State Department's relatively small Anti-Terrorism Assistance (ATA)

program, which provides weapons, equipment, services and training designed

to help foreign governments prevent and deal with terrorist acts. The

State Department's April 2001 aid request indicated plans to increase

ATA funding for Latin America significantly, from $3.0 million in 2000

to $4.4 million in 2002. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 tragedy

in the United States, it is reasonable to expect the ATA account to

increase sharply worldwide, including the Western Hemisphere.

Conclusion

Indeed,

the horrific attacks of September 11 have the potential to alter radically

the United States' relationship with Latin America and its militaries.

As this document goes to publication two weeks after the tragedy, it

is easy to imagine that the U.S. military's main regional concerns during

the 1990s -- the drug war, improving interoperability, developing new

missions and carrying out engagement for its own sake -- have been eclipsed

by a vastly more immediate threat to national security.

While U.S.

policymakers' attention may be diverted to the Middle East, it is unlikely

that military and police assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean

will decrease. In fact, what commentators are calling "America's

new war" might bring increased involvement with the hemisphere's

militaries, as the cold war did during the second half of the twentieth

century.

This new

emphasis may bring several dramatic changes. First, the drug war may

fall to secondary importance among U.S. military priorities in the region.

This would be a tremendous change in Colombia, which is not only a key

drug source country but is also home to groups on the State Department's

list of international terrorist organizations. While U.S. Ambassador

to Bogotá Anne Patterson recently told reporters "there

is no stomach in the United States for counterinsurgency," there

is some possibility that the purpose of aid could nonetheless shift

toward helping Colombia to subdue "terrorist" groups within

its borders.

Secretary

of State Colin Powell indicated that this shift may indeed be underway

in a September 23 television interview: "Quite a few [terrorist

groups] will go after our interests in the regions that they are located

in and right here at home. And so we have to treat all of them as potentially

having the capacity to affect us in a global way. Or to affect our friends

and interests in other parts of the world. For example, we have designated

three groups in Colombia alone as being terrorist organizations, and

we are working with the Colombian Government to protect their democracy

against the threat provided or presented by these terrorist organizations."

In a context

like Colombia's this mission would require a wholesale counterinsurgency

strategy. Yet this strategy would carry the same risks of entanglement

and human rights concerns as before. Should these risks and the policy's

failure become reality, though, U.S. leaders may not be aware of the

need to act, as their attention may remain fixed on the Middle East.

A second

change in U.S. policy toward the region could be a major rollback of

controls and conditions on military assistance that have been put in

place over the past twenty-five years. In a rush to build coalitions

and to guard against this new threat, policymakers may come to view

human rights, nonproliferation, and other protections -- as well as

transparency mechanisms -- as obstacles. The Leahy law, limits on aid

to countries developing nuclear weapons, prohibitions on aid to governments

resulting from military coups, limits on CIA recruitment of known human

rights abusers, and the ban on assassinations of leaders could all be

challenged in coming months.

Yet these

protections are more badly needed now than ever. Assistance to known

abusers and criminals may appear to offer security in the short term,

but history has shown repeatedly that offering aid or a tacit "seal

of approval" to those opposed to our core values -- human rights,

liberty, democracy -- frequently contributes to making volatile regions

even less secure in the long term. Countries and individuals must be

held to an extremely high standard of relevance to U.S. security before

existing protections are waived, and the idea of "blanket waivers"

promises nothing but disastrous results. We must be cautious about reversing

decades of building human rights protections into U.S. foreign policy.

A third

change in U.S. policy toward the region could be an acceleration in

an existing trend of increased military involvement in foreign policymaking.

Already, the many programs documented in this publication have given

the U.S. military a high degree of influence in the Western Hemipshere.

About 50,000 U.S. military personnel pass through the region in a typical

year, many of them carrying out activities that count "engagement"

as a chief mission. As a result, it is already an open question in many

countries which part of the U.S. government -- the diplomats or the

officers -- has the closest relationships with key leaders.

A fourth

potential change is a reduction in oversight of U.S. military programs.

In the few weeks after the September 11 attacks, a Congress normally

fraught with partisanship addressed all national security issues with

near consensus. Once-controversial U.S. military programs like Colombia

and Vieques dropped from sight.

This current

desire for unity is understandable. Nonetheless, oversight of U.S. military

programs -- which is based on the "trust, but verify" concept

-- unavoidably involves controversy at times.

During

the past five years, Congress had made good progress toward better oversight

of U.S. training and counternarcotics programs with Latin America. Congress

has required that the executive provide better information on foreign

military training and Defense Department counter-drug expenditures,

established a requirement for tracking the careers of certain foreign

military personnel trained by the United States, and implemented the

Leahy Law, prohibiting training and assistance to foreign units that

commit human rights abuses. These are all significant improvements in

oversight.

But oversight

is only possible when there is both access to information and a desire

to analyze it. While information may still be produced, the desire to

focus on it may diminish. In the months ahead, policymakers must recall

that U.S. military programs in Latin America continue and that relinquishing

oversight will not make us safer. Those actively pursing oversight and

accountability need and deserve support.

As the

President and Congress move to take strong action against terrorist

threats, they must recall some of the lessons of the past forty years'

U.S. military involvement in Latin America. Probably the most important

is to be careful in choosing our friends -- both those who we train

and with whom we develop long-term alliances. We must choose allies

who do not violate our sense of justice, human rights or democracy.