|

The

Andean ridge countries, especially Colombia, are the focal point

of current U.S. security assistance in the Western Hemisphere. In

1999 four countries – Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru – accounted

for about 90 percent of the cost of U.S. military and police aid

and 50 percent of U.S. trainees.

Assistance

to these countries, the source of much heroin and virtually all

cocaine entering the United States, continues to multiply in 2000

and 2001. Colombia and its neighbors are now receiving the largest

aid package ever granted to Latin America,

a $1.3 billion measure introduced by the Clinton Administration

in January and signed into law on July 13.

The

package was passed in the form of an “emergency supplemental appropriation”

– a special measure that allows the administration to spend money

beyond what was originally budgeted. The supplemental introduces

$729.3 million in military and police assistance to the region during

2000 and 2001, added to existing programs roughly estimated to total

more than $500 million over those two years.

[1]

|

Military

and police assistance

|

Economic

and social assistance

|

Total

|

|

Budget

increases for U.S. counter-drug agencies’ activities in the

region

|

|

|

$223.5

million

|

|

Classified

intelligence program

|

|

|

$55.3

million

|

|

Aid

to Colombia

|

$642.3

million

|

$218

million

|

$860.3

million

|

|

Aid

to Peru

|

$32

million

|

0

|

$32

million

|

|

Aid

to Bolivia

|

$25

million

|

$85

million

|

$110

million

|

|

Aid

to Ecuador

|

$12

million

|

$8

million

|

$20

million

|

|

Aid

to other countries

|

$18

million

|

0

|

$18

million

|

|

Total

|

$729.3

million

|

$311

million

|

$1,319.1

million

|

By

far the largest part of the package is an $860 million outlay for

Colombia, about three-quarters of it for the security forces. In

fact, the aid is often referred to simply as “Plan Colombia,” borrowing

the name of the Colombian government plan that the package intends

to support. The Colombian “plan,” developed with heavy U.S. input,

aims to spend $7.5 billion in foreign and domestic funds to address

Colombia’s interlinked problems of narcotrafficking, civil war,

state neglect, economic crisis, and a weak rule of law.

[2]

This

new aid adds on to about $330 million in ongoing, previously planned

programs (chiefly funds in the State Department and Defense Department

counternarcotics budgets) for Colombia in 2000 and 2001, nearly

all of it police and military aid.

[3]

According

to the annual Foreign Military Training Report,

the United States planned to train 5,086 Colombian military and

police personnel in 2000, more than double the 2,476 trainees the

report cites for 1999. [4]

Among non-NATO countries, only South Korea will have more of

its personnel trained by the United States.

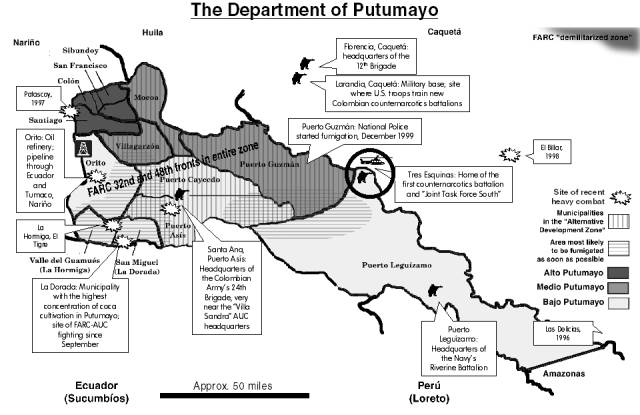

The

bulk of the military portion – $416.9 million – will fund the “push

into southern Colombia.” This Colombian Army operation will require

three newly created battalions to create secure conditions for police

anti-drug activities, including aerial fumigation, in the southern

departments of Putumayo and Caquetá, a coca-growing region dominated

by guerrillas and paramilitary groups. The “push” is scheduled to

begin in January 2001.

These

three battalions, each with about 900 members, are receiving helicopters,

logistical support, intelligence, training and other aid. They will

be headquartered at a base in Tres Esquinas, on the border between

Putumayo and Caquetá departments in southern Colombia. With previously

allocated U.S. funding, the first was assembled in April 1999, began

training a few months later, and has been based at Tres Esquinas

since December 1999. [5]

Once the aid package became law in July 2000, the second battalion

began receiving training from U.S. Special Forces at a Colombian

Army base in Larandia, Caquetá. The second battalion “graduated”

in December 2000, and the third is to be trained from January to

April 2001. [6]

Though

the counternarcotics-battalion strategy began in April 1999 – the

result of a December 1998 agreement between the Pentagon and Colombia’s

Defense Ministry– Congress did not have an opportunity to vote on

it until the 2000 aid package, when the strategy was well underway.

The first battalion’s training and non-lethal equipment were funded

through the Defense Department’s “section 1004”

counter-drug aid authority, which does not require reporting to

Congress. Later aid included a September 1999 drawdown of weapons

and parts, and a “no-cost lease” of U.S.-owned UH-1 helicopters

in November 1999. Neither transfer is subject to legislative approval

or debate, as the law merely requires that Congress be notified.

By the time Congress was asked to fund counternarcotics battalions,

the first unit was already fully trained and equipped.

The

aid package gives the battalions up to sixteen UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters

at a cost of $208 million. The units will also receive up to thirty

UH-1 Huey helicopters, a Vietnam-era aircraft upgraded to a more

powerful “Super Huey” configuration; the Colombian National Police

are to receive another twelve Super Hueys. The battalions will also

fly thirty-three older UH-1N Hueys; eighteen were granted in November

1999 and fifteen are to be delivered in January 2001.

[7]

The

aid package gives $115.6 million to the Colombian National Police

(CNP), previously the largest recipient of U.S. assistance. The

aid to the CNP supports a wide variety of items, from helicopter

upgrades and nine new spray aircraft to training and ammunition.

The largest single police-aid item is a grant of two new UH-60 Blackhawk

helicopters, valued at $26 million. Other police forces, such as

the Judicial Police and Customs Police, will get an additional $7.5

million. [8]

The

CNP, particularly its 2,300-man counternarcotics unit, will continue

to get at least $80 million each year in assistance through regular

channels like the State Department's International Narcotics Control

(INC) program.

[9] This aid funds the police unit's illicit crop eradication,

interdiction, investigations and other counter-drug activities.

U.S.-funded

planes and helicopters spray glyphosate on coca and opium poppy

fields in several areas of the country. A U.S.-supported CNP Air

Service, with over sixty helicopters and airplanes, focuses on poppy

eradication, while Dyncorp, a private U.S. contractor, concentrates

on coca fumigation.

A key

goal of the new aid package is improving the Colombian military’s

intelligence-gathering ability. A focal point is a police-military

Joint Intelligence Center (COJIC), founded with $4.9 million in

U.S. funding, at Tres Esquinas. The facility seeks to increase the

amount of information available to the military about drug and other

activity in southern Colombia, and to increase sharing of this information

between branches of the Colombian armed forces that do not have

a tradition of close cooperation.

[10]

Some

funding in the aid package will benefit U.S. intelligence agencies

working in Colombia. $30 million in Defense Department funds will

buy a new Airborne Reconnaissance Low (ARL) aircraft similar to

the signal-detecting plane that crashed in July 1999 near the border

of Nariño and Putumayo departments.

[11]

Another

$55.3 million funds a classified intelligence program, about which

this study can offer little information. U.S. Southern

Command Chief Gen. Charles Wilhelm (since retired) told a congressional

committee in March 2000, that the classified program is under the

Defense Department’s budget “really for management” reasons. “It

is focused on the activities of two of our agencies and intelligence

community.” [12]

$102.3

million in the 2000-2001 supplemental will fund the Colombian armed

forces' air, river, and ground drug-interdiction operations, military

human rights training, and military justice reforms. Air interdiction

assistance includes upgrades to Colombian Air Force OV-10 and A-37

aircraft, radar upgrades, and improvements to airfields at Tres

Esquinas, Marandúa, Larandia, and Apiay.

[13] Along with the Defense Department’s “section 1033” riverine

counter-drug program, the aid package is funding outboard motors,

ammunition and other assistance to new “riverine combat elements,”

small units within the Colombian Navy’s new Riverine Brigade, based

at Puerto Leguízamo, Putumayo.

[14]

The

aid package includes $13 million to build a new Ground-Based Radar

(GBR) facility at Tres Esquinas to monitor potential aerial drug

smuggling. Three ground-based radars (GBRs) already exist in the

southern Amazon basin area at Leticia, Amazonas department; Marandúa,

Vichada department; and San José del Guaviare, Guaviare department.

Two other radar sites, part of the U.S. Air Force’s Caribbean Basin

Radar Network, are located at Ríohacha in the northern department

of La Guajira, and on the island of San Andrés in the Caribbean

near Nicaragua. [15]

The

battalion strategy and the focus on Colombia’s army represent a

major change in the direction of U.S. aid to Colombia. Before 1999,

Colombia’s National Police received the vast majority of U.S. assistance.

Years of aerial herbicide fumigation of coca (the plant used to

produce cocaine), however, caused cultivation of the crop to move

to the south, in particular to the department of Putumayo along

Colombia’s border with Ecuador. U.S. and Colombian officials consider

Putumayo, a stronghold of the Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces

(FARC) guerrillas, to be too dangerous for the police-centered strategy

followed throughout the 1990s. The State Department’s March 2000

International Narcotics Control Strategy Report indicated

that spray aircraft did not venture more than twenty miles into

the department. [16]

“Our

programs have been designed to focus heavily and increase the capacities

of the Colombia National Police,” Undersecretary of State Thomas

Pickering explained in November 2000. “But given the military threat

that exists on the ground to their operations, also to find ways

to increase the capacities of the Colombian Armed Forces.”

[17]

The

objective of the new Colombian Army counternarcotics battalions,

explains an October 2000 White House report, is to “establish the

security conditions needed” to implement counter-drug programs such

as fumigation and alternative development in Putumayo.

[18] It is reasonable to expect that “establishing security

conditions” will involve the first major armed confrontations between

the new U.S.-aided military units and the FARC guerrillas.

Administration

officials have sought to ease concerns that the “push into southern

Colombia” will inadvertently involve the United States in Colombia’s

civil conflict. “As a matter of administration policy, we will not

support Colombian counterinsurgency efforts,” the October White

House report reads. [19]

In several congressional hearing statements during the spring

of 2000, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and

Low-Intensity Conflict Brian Sheridan asserted that the Pentagon

would not “cross the line” into an anti-guerrilla mission.

I

know that many are concerned that this aid package represents

a step “over the line,” an encroachment into the realm of counterinsurgency

in the name of counternarcotics. It is not. The Department has

not, and will not, cross that line. While I do not have the time

to elaborate on all of the restrictions, constraints, and reviews

that are involved in the approval of the deployment of US military

personnel on counter-drug missions, in Colombia and elsewhere,

it suffices to say that it is comprehensive.

[20]

Armed

groups’ resistance to the U.S.-funded strategy is nonetheless likely,

and Colombia’s FARC guerrillas have already declared U.S. trainers

to be “military targets.” In November 2000, U.S. and Colombian officials

decided to delay the launch of the “push into southern Colombia”

from December 2000 to January 2001, contributing to concerns that

security conditions in Putumayo were worse than planners had anticipated.

“The presence of the armed units of the guerrillas and the paramilitaries

is going to make it more difficult to start more than a few pilot

projects,” warned Undersecretary of State Pickering in November.

[21]

Critics

like House International Relations Committee Chairman Rep. Benjamin

Gilman (R-New York) warn that the U.S.-funded battalions may fail

in the face of guerrilla resistance.

As

recent events in the heavy coca-growing Putomayo (sic) area in

the south of Colombia show, it is evident that the Colombian army

is incapable of controlling any of this guerilla and coca-infested

territory now, or anytime soon. Certainly, three new U.S. trained

counter-narcotics battalions of the Colombian army alone, will

not change this major imbalance on the battlefield. … [O]ne can

easily predict that either the start of army-supported eradication

operations there will continue to be interminably delayed, or

that these operations will be reduced in scope to only small “show

case” interdiction or manual eradication operations (with no real

aerial eradication against the industrial-size coca plots).

[22]

Benchmarks,

planning, and clarity about goals

Several

members of Congress have questioned what they perceive as a lack

of clear, measurable objectives for the new assistance to Colombia

and its neighbors. Solid benchmarks for determining the program’s

success remain elusive. “Nothing in the materials I have seen describes

the Administration's goals with any specificity, what they expect

to achieve in what period of time, at what cost,” Sen. Patrick Leahy

(D-Vermont) said in February 2000.

[23] By October, the White House could still only report that

“specific, quantifiable objectives are currently being negotiated

with the Government of Colombia. The administration will keep the

Congress informed as to the outcome of these discussions.”

[24]

According

to the GAO, the Colombian government bears much blame for the lack

of clarity about goals.

In

early 2000, State [Department] officials began asking the Colombian

government for plans showing, step-by-step, how Colombian agencies

would combat illicit crop cultivation in southern Colombia, institute

alternative means of making a livelihood, and strengthen the Colombian

government’s presence in the area. However, according to State

officials, Colombia’s product, provided in June 2000, essentially

restated Plan Colombia’s broad goals without detailing how Colombia

would achieve them. In response, a U.S. interagency task force

went to Colombia in July 2000 to help the Colombians prepare the

required implementation plan. In September 2000, the Colombian

government provided their action plan, which addressed some of

the earlier concerns.

[25]

Human

rights conditions and Leahy Law implementation

The

supplemental conditioned military assistance on the Colombian armed

forces’ human rights performance, though the conditions were weakened

by an escape clause.

Once

the bill became law (July 13, 2000), and again at the beginning

of fiscal year 2001 (October 1, 2000), new aid could not be “obligated”

(released to be spent) until the Secretary of State certified to

Congress that the following conditions were met:

- The

President of Colombia has issued a written order requiring trials

in civilian courts for all Colombian Armed Forces personnel who

face credible allegations of gross human rights violations;

- The

Commander-General of Colombia's armed forces is promptly suspending

from duty all military personnel who face credible allegations

of gross human rights violations or of assisting paramilitary

groups;

- Colombia's

armed forces are cooperating fully with civilian authorities'

investigations and prosecutions of military personnel who face

credible allegations of gross human rights violations;

- The

Colombian government is vigorously prosecuting paramilitary leaders

and members, and any Colombian military personnel who aid or abet

paramilitary groups, in civilian courts;

- The

Colombian government has adopted a strategy to eliminate all coca

and poppy production by the year 2005. This strategy must include

alternative development programs, manual eradication, aerial spraying

of herbicides, “tested, environmentally safe” mycoherbicides (fungi

that attack drug crops), and the destruction of narcotics-production

laboratories; and

- Colombia's

armed forces are developing and deploying a Judge Advocate General

Corps in their field units to investigate misconduct among military

personnel.

The

supplemental allows these conditions to be skipped entirely if the

President determines that the “national security interest” demands

it. This waiver authority was exercised for all but the first condition

in an August 23, 2000 presidential determination, and a similar

decision appears likely as this publication goes to press in December

2000. [26] Human

Rights Watch, Amnesty International and the Washington Office on

Latin America have an analysis on the Colombian government’s progress

on meeting the human rights conditionality.

This

analysis is available on the Washington Office on Latin America

web site at: http://www.wola.org/colombia_adv_certification_jointstatement.html

These

human rights conditions are in addition to the “Leahy Law,” existing

legislation that suspends assistance to foreign military units whose

members have committed gross human rights violations with impunity.

The 1999 edition of Just the Facts reported that Colombia’s

National Police, Air Force, Navy and Marines were cleared to receive

assistance under the Leahy Law, as were five Army brigades and the

new counter-narcotics battalions. In September 2000, the State Department

confirmed reports that assistance to two of these Army brigades

– the 12th, based in Florencia, Caquetá Department, and the 24th,

based in Santa Ana, just outside Puerto Asís, Putumayo –had been

suspended in compliance with the Leahy Law.

[27]

The

U.S. military presence and the “troop cap”

Funds

in the supplemental may not be used to assign U.S. military personnel

or civilian contractors to Colombia if their assignment would cause

more than 500 troops or 300 contractors to be present in Colombia

at one time. This “troop cap” does not apply to other funds, such

as the Defense Department’s budget or regular anti-drug aid programs

in Colombia. The cap may be exceeded for ninety days if U.S. military

personnel are involved in hostilities, or if their imminent involvement

in hostilities “is clearly indicated by the circumstances.”

[28]

The

cap owes largely to concerns about “force protection” – guaranteeing

the safety of U.S. personnel in the rather hostile environment of

southern Colombia – as well as concerns about the policy implications

of U.S. proximity to Colombia’s conflict.

U.S.

military personnel are in Colombia and other Andean countries carrying

out training, intelligence-gathering, and technical assistance missions.

In 1999, the Southern Command’s Gen. Wilhelm told a congressional

committee, “On our average peak, monthly troop strength in Colombia

was only 209.” [29] This

number is probably higher in late 2000 and early 2001, due to the

ongoing effort to train counternarcotics battalions and to implement

other initiatives foreseen in the aid package.

U.S.

officials state that strict guidelines are in place to shield U.S.

military personnel from Colombia’s violence. “We have expressly

forbidden all of our trainers to engage in or to locate themselves

with Colombian military or other security force units conducting

field operations,” Gen. Wilhelm said in March 2000. Wilhelm added

that the base in Larandia, Caquetá, where most counter-narcotics

battalion training is taking place, “has never once been attacked

by the FARC or other insurgent groups.”

[30]

Contractors

In

fact, the U.S. military presence may not increase sharply along

with the aid package, as civilian contractors working for private

U.S. corporations are carrying out a good deal of the U.S.-funded

cooperation with Colombia’s security forces. In addition to the

Dyncorp spray-plane pilots and mechanics discussed above, contractors

are training Colombian personnel, helping to reform Colombia’s military,

and even flying the helicopters that will transport the counter-narcotics

battalions. The extent of this “outsourcing” – including names of

corporations involved and the range of roles they play – is not

clear, as the law does not require the State and Defense Departments

to make information public on this relatively new phenomenon.

The

Dyncorp contract pilots, one of the most visible examples of this

trend, fly approximately twenty-three State Department-owned helicopters

and airplanes. Including pilots, mechanics, and support staff, Dyncorp

maintains forty-four permanent and sixty-five rotating temporary

staff in Colombia. [31]

The General Accounting Office (GAO) of the U.S. Congress reports

that direct costs of supporting Dyncorp activities in Colombia rose

from about $6.6 million in 1996 to $36.8 million in 1999.

[32] The spray pilots fly over territory where FARC guerrillas

occasionally fire on the planes with small arms. Three contract

pilots have died in two aircraft accidents: a 1997 crash blamed

on pilot error and a 1998 accident in which the cause remains uncertain.

[33]

Another

often-cited example is a multi-year contract with Military Professional

Resources International (MPRI), a Virginia-based company staffed

mainly by retired U.S. military officers. The Defense Department

has hired MPRI to conduct a thorough review of the Colombian military,

offering comprehensive recommendations for making it a more effective

institution. Gen. Wilhelm explained the MPRI contract to the House

Armed Services Committee.

We

have engaged the services of Military Professional Resources,

Incorporated (MPRI). Hand-picked and highly experienced, MPRI

analysts will assess Colombia's security force requirements beyond

the counter-drug battalions and their supporting organizations.

The contract that [Assistant Defense Secretary Brian] Sheridan's

people have developed and negotiated with MPRI tasks them to develop

an operating concept for the armed forces, candidate force structures

to implement that concept and the doctrines required to train

and equip the forces.

[34]

“The

MPRI contract cost $3 million,” added the Pentagon’s Brian Sheridan

at the same hearing, explaining the decision to hire a contractor.

What

are we doing with MPRI that Southern Command or someone else can't

do? In theory, nothing. If Gen. Wilhelm had unlimited manpower,

he would be able to send 15 people permanently to work at the

Colombian Ministry of Defense to help them organize a new structure,

he'd be able to send 6-man teams down on a temporary basis to

help them focus on certain problem areas and he'd help them reform

the Colombian military. But when you look at the reality of the

staffing that U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) has, we don't have

the manpower to do this.

[35]

Critics

worry that, as they are not official representatives of the U.S.

government in Colombia, the contractors are less accountable than

uniformed military personnel. As a result, there is concern that

contract personnel may come to fill roles that go beyond the narrow

counter-drug mission, and that since contractor casualties would

be less controversial, they may perform tasks and operate in zones

that would be off-limits to regular government or military officials.

These concerns are necessarily based on speculation, however, because

of the lack of transparency surrounding the contractors’ activities.

Problems

with the delivery of assistance

Though

it has been active at Tres Esquinas since December 1999, the first

Colombian Army counternarcotics battalion has been limited for over

a year by a lack of trained pilots to fly the eighteen UH-1N Huey

helicopters it received in late 1999. In early 2000, a U.S. contractor

was training twenty-four civilian contract pilots and twenty-eight

Colombian Army co-pilots; the plan was to have the aircraft ready

for use by May 2000. [36]

The

GAO reports, however, that the State Department “had not included

the funds necessary to procure, refurbish, and support” the Hueys

in its budget, and was forced to await congressional approval of

the “Plan Colombia” aid package, which did not occur until July.

“Because of the lack of funds,” the GAO states, “17 of the 24 contractor

pilots trained to fly the 18 UH-1Ns were laid off beginning in May

2000. In August 2000, State reprogrammed $2.2 million from the U.S.

counternarcotics program for Mexico to rehire and retrain additional

personnel.” [37] As

of October 2000, the White House reported, “There are currently

47 Colombian Army officers in various stages of pilot training in

the United States and Colombia,” but the first battalion was still

restricted to operations on land for lack of pilots.

[38]

The

next battalions are also expected to “go on-line” well in advance

of their helicopters. While the second battalion finished training

in December 2000 and the third is to be ready in April 2001, the

units will be limited to the older Hueys until at least the middle

of 2001, when the first Blackhawks and “Super Hueys” are to begin

arriving. [39] In fact,

U.S. officials had originally predicted that the first Blackhawks

would not begin arriving until the end of 2002; faced with stiff

congressional criticism, however, they announced a revised delivery

schedule in October 2000.

[40]

Spillover

Colombia’s

neighbors and other observers are concerned that the “push into

southern Colombia” may send violence, refugees and drug cultivation

across Colombia’s porous borders into Brazil, Ecuador, Panama, Peru

and Venezuela. The U.S. aid package included $180 million for Colombia’s

neighbors, mainly Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru. Of this amount, just

over half – $93 million – will fund alternative-development programs

to wean coca-growers away from the drug trade. The rest is military

and police assistance.

[41]

Undersecretary

of State Pickering acknowledged the spillover risk in November,

indicating that post-2000 aid increases will focus more on the entire

region, not just Colombia.

It

is clear that as we increase our efforts in Colombia, there will

be a tendency to find new areas, either in Colombia or outside of

Colombia, in which to move the cultivation and production of cocaine

and heroin, wherever it is appropriate. And so we are now thinking

very clearly of a regional program … as a centerpiece of next year's

effort to support the Andean region.

[42]

The

supplemental roughly doubles existing programs for Ecuador by contributing

$20 million: $12 million for drug interdiction and $8 million for

alternative development programs. The $12 million for Ecuador’s

security forces will be spent as follows, according to a July 2000

State Department report.

The

Department plans to use $12 million to create and improve border

checkpoints along the Colombian border, and to improve communications,

mobility, interoperability and intelligence collection and information

sharing among the police and military units in the northern border

regions. Additionally, funding will improve port security and

inspection facilities along the coast.

[43]

According

to the annual Foreign Military Training Report, the United States

trained 681 Ecuadorian military and police personnel in 1999.

[44] U.S. Special Forces (SOF) units deployed

to Ecuador on training missions at least sixteen times in 1999,

almost always for counter-drug training.

[45] Another twelve SOF counter-drug training deployments were

foreseen for 2000. [46]

Ecuador

also hosts a counter-drug “Forward Operating Location” (FOL)

at Manta, on the Pacific coast about 200 miles south of the Colombian

border. Under this arrangement, U.S. aircraft on detection and monitoring

missions have access to airport facilities. Small numbers of military,

DEA, Coast Guard and Customs personnel are stationed at the FOL

to support the U.S. aircraft and to coordinate communications and

intelligence. The supplemental provides $61.3 million for the Manta

facility, which will be used largely for paving, hangars, and maintenance

facilities. [47]

The

supplemental roughly doubles existing programs for Bolivia as well,

contributing $110 million: $25 million for drug interdiction and

$85 million for alternative development programs. The $25 million

for Bolivia’s security forces will support President Hugo Banzer’s

ongoing military coca-eradication campaign in the Chapare, a jungle

region in eastern Bolivia, according to a July 2000 State Department

report.

The

Department plans to use $25 million to support interdiction and

eradication efforts in the Chapare and Yungas coca growing regions.

Funding will also support border control and inspection facilities

on the Paraguayan/Argentinean/Brazilian borders; improved checkpoints

in the Chapare; intelligence collection; training for helicopter

pilots and C-130 pilots and mechanics; spare parts for C-130 aircraft,

helicopters and riverine boats; vehicles; training for police

and controlled substance prosecutors; and justice sector reforms.

[48]

The

United States planned in 2000 to use funds in the Defense Department’s

“section 1004” counter-drug budget to build three base camps for

Bolivian Army coca-eradication forces in the Chapare. (Section 1004(b)(4)

of the 1991 National Defense Authorization Act allows the Pentagon

to use its counter-drug budget for “the establishment and operation

of bases of operations or training facilities.”) At a cost of $6.4

million, the Southern Command planned to build a brigade headquarters

and three 520-man facilities at Chimore, Fonadal and Ichoa. The

sites, according to a Southern Command document, would have allowed

the Bolivian Army to “maintain a presence and prevent narco-traffickers

from taking over once the strong government presence departs” following

the Chapare eradication campaign.

[49]

Bolivia

was convulsed in late September and early October by massive protests

of Chapare peasants affected by the eradication campaign. One of

the protestors’ main demands was that Bolivia abandon its plan to

establish the three new barracks. The Bolivian government agreed

to this demand, leaving the U.S. construction funds unspent. It

is currently unclear how these funds will be used; improvements

to existing facilities are a likely alternative.

According

to the annual Foreign Military Training Report, the United States

trained 2,152 Bolivian military and police personnel in 1999.

[50] This study was able to identify nineteen Special Forces

training deployments to Bolivia in 1999, between the JCET program

and counter-drug training.

[51]

The

supplemental provides $32 million to purchase up to five KMAX helicopters

for Peru’s National Police (PNP). The aircraft, the State Department

reports, will replace Peru’s “operationally expensive and unreliable

Russian MI-17 helicopters.” The aid will train pilots and mechanics

and provide four years’ spare parts and logistical and technical

support. [52]

The

Southern Command’s 2000 “Posture Statement” cites “steady progress”

in the United States’ riverine counter-drug aid program for Peru’s

Navy and Police, made possible by the Defense Department’s “section

1033” budget authorization.

With

U.S. Assistance, the Peruvians have established the Joint Peru

Riverine Training Center near Iquitos in the Amazon region. …

During the past year four of 12 planned Riverine Interdiction

Units (RIU) have been fielded and pressed into service. With currently

approved funding we will assist Peru to expand its riverine capabilities

by providing them twelve 25-foot patrol boats, six 40-foot patrol

craft, spare parts, night vision devices and essential items of

individual equipment.

[53]

According

to the annual Foreign Military Training Report, the United States

trained 983 Peruvian military and police personnel in 1999.

[54] Peru hosted one U.S. Special Forces Joint Combined Exchange

Training (JCET) deployment in 1999. According to the annual Foreign

Military Training Report, however, the Special Forces conducted

no counter-drug training in Peru in 1999. The report foresees two

Special Forces counter-drug deployments and one Marine Corps riverine

training deployment in 2000.

[55]

Concerns

over the now-departed Fujimori government’s anti-democratic behavior

were reflected in Section 530 of the 2001 Foreign Operations, Export

Financing and Related Programs Appropriations Act (H.R. 5526, Public

Law 106-429). This measure requires the Secretary of State to issue

a report every 90 days during 2001 determining “whether the Government

of Peru has made substantial progress in creating the conditions

for free and fair elections, and in respecting human rights, the

rule of law, the independence and constitutional role of the judiciary

and national congress, and freedom of expression and independent

media.” If the report finds that substantial progress has not been

made, section 530 prohibits further assistance to Peru’s central

government. [56]

The

supplemental for Colombia and its neighbors includes smaller amounts

for other countries in the region. Brazil will get $3.5 million

to upgrade intelligence collection in its Amazon basin, to support

construction of a Brazilian radar network (known as SIVAM), and

to provide small boats for riverine drug interdiction. Through a

transfer via the U.S. defense budget, Brazil is also receiving several

ships, including four frigates. Panama will receive $4 million to

create a 25-member Technical Judicial Police (PTJ) task force, to

support the National Maritime Service’s patrol boats, and to support

border control programs. $3.5 million will help Venezuela’s Technical

Judicial Police (PTJ) and National Guard carry out ground and port

interdiction, and will support judicial reform, drug policy coordination

and domestic drug demand-reduction programs.

[57]

Since

June 1999, the government of President Hugo Chávez has consistently

denied U.S. requests to allow counter-drug aircraft to enter Venezuelan

airspace for intelligence missions or pursuit of suspected drug

traffickers. “Since May 27, 1999,” the Southern Command’s Gen. Wilhelm

told a Senate caucus in February 2000, “the Government of Venezuela

has denied 34 of 37 U.S. requests for overflight in pursuit of suspect

aircraft.” [58]

The

supplemental approved in July 2000 provides enhanced funding only

for 2000 and 2001. In mid-2001, as Colombia’s counternarcotics battalions

receive their helicopters and carry out their “push to the south,”

Congress will consider an aid request from the new Bush administration

to support programs in the Andes during 2002. Since most initiatives

from the previous aid package will barely be underway, this request

will probably be aimed more at maintaining current efforts than

at beginning new ones – though aid to Colombia’s neighbors is likely

to rise significantly.

Plans

for the more distant future are less clear. According to the White

House’s October report on its objectives in Colombia, the plan “will

extend to cover the entire country over a six-year period.”

[59] Gen. Wilhelm, the Southern Command chief, discussed this

six-year plan for Colombia aid a bit more specifically at a House

committee hearing: “The first two years are to the south, the second

two years are to the east toward the Meta and Guaviare provinces,

and the years five and six move to the north to Santander and the

other provinces where the drugs are grown.”

[60]

In

the end, there are too many variables and uncertainties – not least

among them a change of power in the U.S. executive – to predict

where U.S. assistance to the Andean countries is headed over the

next few years. Engagement with the region’s militaries, however,

is virtually certain to remain very close. For the foreseeable future,

the Andes are likely to continue accounting for more than nine out

of every ten dollars of U.S. security assistance to the hemisphere.

Sources:

[1] For aid amounts, see:

Title III, Division B, Military Construction Appropriations bill,

2001, H.R. 4425, Public Law 106-246, Washington, DC, July 13, 2000

< http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c106:H.R.4425.ENR:>.

House-Senate Conference Committee report 106-710, Washington, DC,

June 29, 2000 <http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/cpquery/R?cp106:FLD010:@1(hr710)>.

United States, Department of State, “Report to Congress,” Washington,

DC, July 27, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/080102.htm>.

United States, The White House, “Proposal for U.S. Assistance to Plan

Colombia,” Washington, DC, February 3, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/aidprop4.htm>.

United States, The White House, “Report On U.S. Policy And Strategy

Regarding Counter-drug Assistance To Colombia And Neighboring Countries,”

Washington, DC, October 26, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/102601.htm>.

[2]

Government of Colombia, “Plan Colombia: Plan for Peace, Prosperity,

and the Strengthening of the State,” Bogotá, Colombia, October 1999

<http://www.presidencia.gov.co/webpresi/plancolo/index.htm>.

[3]

The White House, February 3, 2000.

[4]

United States, Department of State, Department of Defense, “Foreign

Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest In Fiscal

years 1999 and 2000, Volume I,” Washington, DC, March 1, 2000 <http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/fmtrain/toc.html>.

[5]

For descriptions of the battalion-based strategy, see:

The White House, October 26, 2000.

Statement Of Brian Sheridan, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special

Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict, Usnited States House Of Representatives,

Committee On Government Reform, Subcommittee On Criminal Justice,

Drug Policy, and Human Resources, Washington, DC, October 12, 2000

<http://usinfo.state.gov/admin/011/lef401.htm>.

Sen. Joseph Biden (D-Delaware), “Aid to ‘Plan Colombia:’ The Time

for U.S. Assistance is Now,” Report to the U.S. Senate Committee on

Foreign Relations, Washington, DC, May 3, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/050302.htm>.

United States Southern Command, “Posture Statement Of General Charles

E. Wilhelm, United States Marine Corps Commander In Chief, United

States Southern Command,” delivered before the House Armed Services

Committee, Washington, DC, March 23, 2000 <http://www.house.gov/hasc/testimony/106thcongress/00-03-23wilhelm.htm>.

General Barry R. McCaffrey, Director, Office of National Drug Control

Policy, “Emergency Supplemental Request for Assistance to Plan Colombia

and Related Counter-Narcotics Programs,” Statement before the House

Appropriations Foreign Operations Subcommittee, Washington, DC, February

29, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/022903.htm>.

General Barry R. McCaffrey, Director, Office of National Drug Control

Policy, “US Counter-drug Assistance for Colombia and the Andean Region,”

Statement before the Senate International Narcotics Control Caucus

and Finance Committee, Subcommittee on International Trade, Washington,

DC, February 22, 2000 <http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/news/testimony/022200/index.html>.

General Charles E. Wilhelm, United States Marine Corps, Commander-In-Chief,

United States Southern Command, Statement before the House Committee

on Government Reform, Subcommittee On Criminal Justice, Drug Policy

And Human Resources, Washington, DC, February 15, 2000 <http://usinfo.state.gov/regional/ar/colombia/aid15.htm>.

General Barry R. McCaffrey, Director, Office of National Drug Control

Policy, “Colombian and Andean Region Counter-drug Efforts: The Road

Ahead,” Statement before the House Committee on Government Reform,

Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy, and Human Resources,

Washington, DC, February 15, 2000 <http://usinfo.state.gov/regional/ar/colombia/mccaf15.htm>.

The White House, February 3, 2000.

United States, Department of Defense, “Colombia Supplemental,” Washington,

DC, January 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/aidprop3.htm>.

[6]

The White House, October 26, 2000.

Sheridan, October 12, 2000.

[7]

The White House, October 26, 2000.

Rand Beers, Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics

and Law Enforcement Affairs, Statement before the Criminal Justice,

Drug Policy, and Human Resources Subcommittee of the House Committee

on Government Reform, Washington, DC, October 12, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/101202.htm>.

[8]

Military Construction Appropriations bill.

House-Senate Conference Committee report 106-710.

Department of State, July 27, 2000.

The White House, February 3, 2000.

The White House, October 26, 2000.

[9]

The White House, October 26, 2000.

[10]

United States Southern Command, March 23, 2000.

Wilhelm, February 15, 2000.

General Charles E. Wilhelm, United States Marine Corps, Commander

in Chief, United States Southern Command, Statement before the Senate

Caucus on International Narcotics Control, September 21, 1999 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/00092104.htm>.

[11]

United States House of Representatives, Committee on Armed Services,

Transcript of Hearing, Washington, DC, March 23, 2000 <http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/security/has083000.000/has083000_0f.htm>.

United States Senate, Committee Report 106-290, Washington, DC, May

11, 2000 <http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/cpquery/R?cp106:FLD010:@1(sr290)>.

[12]

Committee on Armed Services, March 23, 2000.

[13]

Department of State, July 27, 2000.

[14]

United States Southern Command, March 23, 2000.

[15]

Walter B. Slocombe, undersecretary of defense for policy, United

States Department of Defense, letter in response to congressional

inquiry, April 1, 1999.

Military Construction Appropriations bill.

House-Senate Conference Committee report 106-710.

The White House, February 3, 2000.

[16]

United States, Department of State, International Narcotics

Control Strategy Report, Washington, DC, March 1, 2000 <http://www.state.gov/www/global/narcotics_law/1999_narc_report/samer99_part3.html>.

[17]

United States, Department of State, “On-The-Record Briefing: Under

Secretary Pickering on His Recent Trip to Colombia,” Washington, D.C.,

November 27, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/112701.htm>.

[18]

The White House, October 26, 2000.

[20]

Sheridan, October 12, 2000.

Brian E. Sheridan, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations

and Low Intensity Conflict, Statement before the United States House

of Representatives Committee on International Relations Subcommittee

on Western Hemisphere, Washington, DC, September 21, 2000 <http://www.house.gov/international_relations/wh/colombia/sheridan.htm>.

Brian E. Sheridan, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations

and Low Intensity Conflict, Statement before the United States Senate

Committee On Armed Services, Washington, DC, April 4, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/040402.htm>.

Brian E. Sheridan, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations

and Low Intensity Conflict, Statement before the House Armed Services

Committee, Washington, DC, March 23, 2000 <http://www.house.gov/hasc/testimony/106thcongress/00-03-23sheridan.htm>.

Brian E. Sheridan, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations

and Low Intensity Conflict, Statement before the House Committee on

Appropriations Subcommittee on Foreign Operations, Export Financing

And Related Agencies, Washington, DC, February 29, 2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/022904.htm>.

[21]

Department of State, November 27, 2000.

[22]

Rep. Benjamin Gilman, letter to Gen. Barry McCaffrey, director,

White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, November 14, 2000

<http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/111401.htm>.

[23]

Sen. Patrick Leahy, Statement before hearing of the Foreign Operations

Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee, February 24,

2000 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/022401.htm>.

[24]

The White House, October 26, 2000.

[25]

General Accounting Office, October 17, 2000.

[26]

The White House, “Memorandum Of Justification in Connection With

the Waivers Under Section 3201(A)(4) of the Emergency Supplemental

Act, as Enacted in the Military Construction Appropriations Act, 2001,”

Washington, DC, August 23, 2000 <http://www.pub.whitehouse.gov/uri-res/I2R?urn:pdi://oma.eop.gov.us/2000/8/23/7.text.1>.

[27]

William Brownfield, deputy assistant secretary of State for Western

Hemisphere Affairs, on-the-record briefing, Washington, DC, September

29, 2000.

[28]

Military Construction Appropriations bill, 2001.

[29]

United States House of Representatives, Committee on Armed Services,

March 23, 2000.

[31]

United States, State Department, Inspector-General, “Report of

Audit: Review Of INL-Administered Programs In Colombia,” Report number

00-CI-021, Washington, DC, July 2000 <http://oig.state.gov/pdf/00ci021.pdf>.

[32]

United States, General Accounting Office, “Drug Control: U.S.

Assistance to Colombia Will Take Years to Produce Results, Report

number NSIAD-01-26, Washington, DC, October 17, 2000 <http://www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?rptno=GAO-01-26>.

[33]

State Department, Inspector-General, July 2000.

[34]

United States House of Representatives, Committee on Armed Services,

March 23, 2000.

[36]

General Accounting Office, October 17, 2000

[38]

The White House, October 26, 2000.

[40]

Beers, October 12, 2000.

[41]

Military Construction Appropriations bill.

House-Senate Conference Committee report 106-710.

Department of State, July 27, 2000.

The White House, February 3, 2000.

The White House, October 26, 2000.

[42]

Department of State, November 27, 2000.

[43]

Department of State, July 27, 2000.

[44]

United States, Department of State, Department of Defense, “Foreign

Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest In Fiscal

years 1999 and 2000, Volume I,” Washington, DC, March 1, 2000 <http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/fmtrain/toc.html>.

[45]

United States, Department of State, Department of Defense, “Foreign

Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest In Fiscal

years 1999 and 2000, Volume I,” Washington, DC, March 1, 2000 <http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/fmtrain/toc.html>.

United

States, Defense Department, State Department, "Foreign Military

Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest In Fiscal Years

1998 and 1999: A Report To Congress," Washington, March 1999:

3-4.

[46]

United States, Department of State, Department of Defense, “Foreign

Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest In Fiscal

years 1999 and 2000, Volume I,” Washington, DC, March 1, 2000 <http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/fmtrain/toc.html>.

[47]

United States Southern Command, "Information on Forward Operating

Location Manta (Eloy Alfaro Int'l Airport)," Document obtained

November 2000.

The White House, October 26, 2000.

[48]

Department of State, July 27, 2000.

[49]

United States Southern Command, “Bolivian Army Base Camp Construction

Information Paper,” January 19, 2000, Document obtained November 2000.

[50]

United States, Department of State, Department of Defense, “Foreign

Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest In Fiscal

years 1999 and 2000, Volume I,” Washington, DC, March 1, 2000 <http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/fmtrain/toc.html>.

[51]

United States, Defense Department, "Report on Training of

Special Operations Forces for the Period Ending September 30, 1999,"

Washington, April 1, 2000.

United States, Department of Defense, Department of State, Foreign

Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest in Fiscal

Years 1999 and 2000: A Report to Congress (Washington: March 2000)

<http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/fmtrain/toc.html>.

United States, Defense Department, State Department, "Foreign

Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest In Fiscal

Years 1998 and 1999: A Report To Congress," Washington, DC, March

1999: 1, 11.

[52]

Department of State, July 27, 2000.

[53]

United States Southern Command, March 23, 2000.

[54]

United States, Department of Defense, Department of State, Foreign

Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest in Fiscal

Years 1999 and 2000: A Report to Congress (Washington: March 2000)

<http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/fmtrain/toc.html>.

[55]

United States, Defense Department, "Report on Training of

Special Operations Forces for the Period Ending September 30, 1999,"

Washington, April 1, 2000.

United

States, Department of Defense, Department of State, “Foreign Military

Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest in Fiscal Years

1999 and 2000: A Report to Congress” (Washington: March 2000) <http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/fmtrain/toc.html>.

[56]

Foreign Operations, Export Financing and Related Programs Appropriations

Act, 2001, H.R. 4811, Public Law 106-429, Washington, DC, November

6, 2000 <http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c106:H.R.4811.ENR:>.

[57]

Department of State, July 27, 2000.

[58]

General Charles E. Wilhelm, United States Marine Corps, Commander-In-Chief,

United States Southern Command, Statement before the Senate Caucus

on International Narcotics Control and the Senate Finance Committee,

Subcommittee on International Trade, Washington, DC, 22 February 2000

<http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/aid/022207.htm>.

[59]

The White House, October 26, 2000.

[60]

United States House of Representatives, Committee on Armed Services,

March 23, 2000.

Colombia (2001 narrative)

|