|

| Home | | |

Analyses | | |

Aid | | |

| |

| |

News | | |

| |

| |

| |

| Last

Updated:4/12/02 |

| Testimony

of Adam Isacson, senior associate, Center for International Policy, April

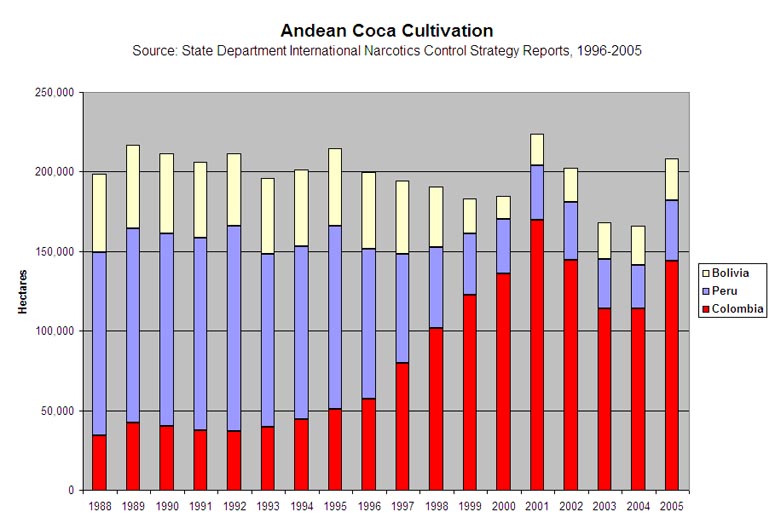

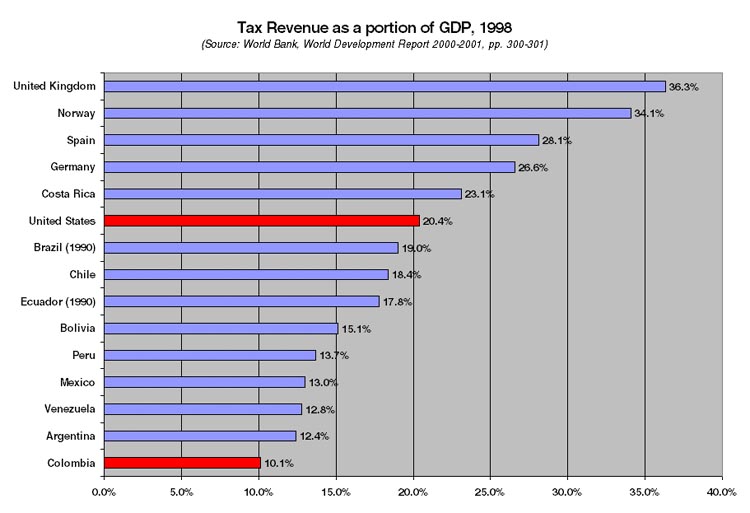

11, 2002 Testimony Adam Isacson Senior Associate, Center for International Policy April 11, 2002 Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere, House International Relations Committee Chairman Ballenger, Ranking Member Menendez, I thank you for the opportunity to testify before your subcommittee today on U.S. policy toward Colombia. This is a crucial moment in Colombia. A month and a half ago, three years of peace talks with the Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces (FARC) guerrillas broke down. A month and a half from now, Colombia will hold a very important presidential election. This is also a crucial moment for the United States’ policy toward Colombia. This year, the administration’s 2003 Foreign Operations request asks Congress for significant amounts of non-drug military assistance for the first time since the Cold War, most of it equipment and training to help defend an oil pipeline. The emergency supplemental legislation also before Congress would go still further, allowing all previous narcotics-related military assistance – including the contents of the 2000 “Plan Colombia” aid package – to be used in a “unified campaign against narcotics trafficking, terrorist activities, and other threats to its national security.”[1] Broadening our military assistance mission in Colombia beyond counter-narcotics is a major departure. This may be the last time we get to debate such a qualitative change; future debates will center not on whether we should be involved in Colombia’s conflict, but how deeply we should be involved. It is important that Congress thoroughly consider the consequences of what it decides this year. My study of Colombia over the past few years has convinced me that these consequences could be very serious for both of our countries. Why the focus on counter-narcotics? The Center for International Policy has always opposed the United States’ overwhelming focus on the drug issue in Colombia. It is obvious to all that Colombia’s problems go well beyond narcotics, and we have argued for years that our emphasis on military responses and fumigation would do little more than push drug cultivation around the map of South America. (See figure 1 at the end of this document.) But I understand why past administrations chose to limit our military-assistance mission to the drug war – and it was more than just political expedience. On some level, our security planners were aware of the challenge Colombia’s conflict presents and the commitment that taking on its armed groups would require. Colombia is a big country, its illegal armed groups are large and well-funded from a variety of sources (including drugs), and the conflict’s roots are old and complex. The military’s small size and chronic human rights problems are symptoms of years of institutional neglect and lack of professionalization. The guerrillas’ strength is also a symptom of the government’s historical neglect of rural Colombia. The amount that what needs to be done is daunting, and anyone who promises a short-term solution is, quite simply, a fool. As a result, until now U.S. policymakers had concentrated their aid resources where they thought they could make a difference – fighting drugs, which not only poison our citizens but fuel Colombia’s conflict. CIP disagreed with the choice of concentrating resources on the military, which failed to address the reasons people grow drugs to begin with, and threatened to bring us closer to entanglement in the conflict. But as our resources have been limited to roughly half a billion dollars over each of the past few years, the broader idea of focusing on one aspect of Colombia’s crisis made some strategic sense – even though we’ve seen virtually no impact on the drug trade so far. Stretching U.S.-provided military assets – creating demand for more military aid Since 2000, the United States has provided Colombia’s about $1.35 billion in military and police aid. (See table 1 at the end of this document.) Most of the aid to Colombia’s army adds up to a 2,300-man counter-narcotics brigade and about 75 helicopters. This is perhaps enough, if not to eliminate the presence of armed groups, at least to alter the military balance in an area like Colombia’s drug-infested Putumayo department, which is about the size of the state of Maryland. But Colombia is the size of Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma combined. If we broaden the mission of our aid beyond drugs, we will dramatically increase the number of targets that these units and helicopters can be employed against. We may find very soon that these assets are spread way too thinly, and thus unable to respond to the majority of requests for their use. Armed groups will continue to attack military and civilian targets and infrastructure, and we will soon find that our assistance has made little difference in the overall direction of the conflict. This will generate enormous pressure in out-years (perhaps as soon as 2003) for substantial military aid increases: more helicopters, more training, more weapons, more units. Perhaps more U.S. personnel acting as instructors and advisors. How will Congress respond to that pressure? How far are we willing to go in Colombia? Responsibility demands that we answer these questions now rather than later. It is disingenuous to call a broader mission in Colombia “counter-terrorism.” That makes it sound like a relatively small effort. But Colombia is not the Philippines, Georgia, or Yemen. Certainly, the FARC, the smaller National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrillas, and the rightist paramilitaries of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) are all on the State Department’s list of terrorist organizations, and all commit acts of terrorism. But these groups have been fighting for decades – some can even trace their origins as far back as 1948. Together, they have roughly 40,000 members. (See table 2 at the end of this document.) Unlike most terrorist groups, they control territory and even govern it, however crudely and brutally. They are organized as military forces, well-armed and equipped with extensive intelligence capabilities. They earn hundreds of millions of dollars per year in ill-gotten profits, much from the drug trade. The FARC has even proven able to carry out military-style attacks on army bases. By comparison, the Abu Sayyaf organization in the Philippines has only a few hundred members and is confined to parts of a small island. Confronting Colombia’s groups militarily would mean supporting a long and costly counter-insurgency campaign, many times larger than all military aid we have given Colombia so far. Calling it “counter-terrorism” and changing the purpose of past aid would be nothing more than a tiny first step. The small size of Colombia’s armed forces increases the potential for U.S. overcommitment. Currently, the Colombian Army has about 150,000 members, but only about 40,000 of them can be deployed into battle.[2] The rest are at desk jobs or tied down to guarding static infrastructure like pipelines and power lines. This force would need to triple or quadruple in size to take on the insurgents effectively. In fact, a 1999 paper on Colombia from the U.S. Army War College argues, “Conventional wisdom holds that a successful counter-insurgency requires a ratio of 10 soldiers to 1 guerrilla. … Even if the army were to achieve the 10 to 1 force ratio, it might still not be enough to ‘saturate’ the country.”[3] Colombia’s defense needs are simply too great for U.S. aid alone to make a difference, and any attempt to fill the gap unilaterally could be disastrous. Colombia’s contribution Worse, it is far from clear whether Colombia’s leadership – the ten percent that earn 42 times in a year what the bottom ten percent earn, or the three percent of landholders who control 70 percent of farmland – would be committed to joining the United States in sharing the burden of a serious war effort.[4] Current Colombian law excludes conscripts with high school degrees – meaning all but the poor – from service in combat units.[5] The World Bank's figures show that Colombians pay only 10.1 percent of GDP in taxes – half the U.S. figure and lower than most of Latin America; in the United States during World War II, taxes and war bonds ate up nearly 40 percent of GDP.[6] (See figure 2 at the end of this document.) Colombia's National Association of Financial Institutions (ANIF) reports that Colombia spends only 1.97 percent of GDP on defense, despite having been at war for decades.[7] Worse, much of what is raised ends up lost to corruption. The “corruption perceptions index” maintained by Berlin-based Transparency International ranks Colombia 50th on a list of 91 countries.[8] In a 2001 report, the Army War College report reminds us, “The history of counterinsurgency support teaches that for the ally in the field to win, the United States should not make the sacrifices for it. The sacrifices in this case must be borne by the people of Colombia.”[9] At present, however, Colombia's will to sacrifice is in doubt. The El Salvador analogy At first glance, the question of elite commitment and slowly escalating U.S. military aid may remind some of Vietnam during the Kennedy administration. The Vietnam analogy is inappropriate, however – it is difficult to imagine U.S. ground troops in Colombian jungles. But a costly and difficult military commitment is certainly a plausible outcome of the current strategy. A more apt comparison, at least on a very basic level, may be the U.S. experience in El Salvador. In fact, many U.S. advocates of greater counter-terror / counter-insurgency aid to Colombia – such as the Rand Corporation, in a June 2001 report – hold up U.S. support for El Salvador in the 1980s as a possible model for Colombia.[10] However, these analysts’ reading of El Salvador invariably neglects to recall that it took twelve years and nearly two billion dollars of military aid to achieve only a stalemate in El Salvador, after fighting killed 70,000 people and exiled over a million. Since Colombia has fifty-three times the area and eight times the population of El Salvador, the cost of a “successful” counter-insurgency campaign could be nightmarishly high, whether measured in dollars or lives. Links between the military and paramilitaries Even if Colombia’s military could somehow be brought to the strength needed to secure all of the country’s territory, U.S. aid would still have disastrous consequences if lingering ties between the armed forces and rightist paramilitaries continue to go unaddressed. It alarms and sickens many to think that our assistance could indirectly benefit a group that is responsible for the vast majority of Colombia’s killings, disappearances and forced displacement of civilians. Due to the Colombian military’s well-documented ties to the paramilitaries, as well as the impunity enjoyed by officers credibly alleged to have been involved in abuses, the U.S. government was unable to certify that its aid recipients met a series of human rights conditions that Congress included in the 2000-2001 aid package law. (President Clinton chose to waive the conditions, as the law allowed, citing “the national security interest.”) While a delayed and highly contested certification is likely soon, the State Department’s March 4 human rights report reminds us that “members of the security forces sometimes illegally collaborated with paramilitary forces” throughout 2001.[11] Collusion between the Colombian military and the terrorists of the right is continuing. The following examples are taken from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’ just-released report on Colombia, which notes that “the Office continued receiving disturbing information about ties between the armed forces and paramilitary groups” throughout 2001.[12]

In addition, during visits to Colombia in February and April, the Center for International Policy heard numerous testimonies from elected officials, ombudsmen, community leaders, and human rights defenders about continuing – and even increasing – military-paramilitary collusion, particularly blatant military and police tolerance of paramilitary activity, in Nariño, Cauca, and Norte de Santander departments. The paramilitaries, who many tax-paying Colombians may view as a cheaper, quicker option than multiplying the size of their military, are getting stronger. They are the fastest-growing of Colombia’s armed groups, increasing from about 4,000 in 1998 to about 14,000 today, and their leaders say they aim to double in size again by next year. They have made significant territorial gains, moving from traditional strongholds like northwestern Colombia and the Middle Magdalena region to town centers in many longtime guerrilla strongholds in southern Colombia and elsewhere. The paramilitaries also fund themselves through the drug trade, and not just because Colombia’s drug lords are among their longtime benefactors. Like the guerrillas, the paramilitaries tax coca and heroin-poppy in areas where they are strong. The so-called “political director” of the AUC, the media-savvy Carlos Castaño, has admitted in interviews that his group gets about 70 percent of its funding from the drug trade.[13] Many are turning a blind eye to these drug links, though, as the guerrillas’ behavior has increased the death squads’ political acceptance. The candidate leading polls for the May presidential elections, hard-liner Alvaro Uribe, is promising to arm a million more civilians.[14] On a February visit, I heard several reports of paramilitaries gathering townspeople and instructing them to vote for Uribe. While this does not mean that Uribe will foster the paramilitaries, the rightist groups’ support must indicate a belief that he will go easy on them. Human rights conditions Broadening the mission of U.S. assistance beyond counter-narcotics may mean allowing U.S. aid to be used all over the country, possibly including many areas where the military is frequently alleged to be colluding with paramilitaries. Under the “Leahy Law” human rights protections, U.S. personnel are checking the names of recipient-unit members against a database of known violators. The administration’s supplemental appropriations request, as currently written, would keep the Leahy protections but would do away with the Colombia-specific language in the 2002 Foreign Operations Appropriations law, which were designed as a crucial additional safeguard against indirect U.S. support for paramilitaries. It is our belief that while the Leahy Law is an important tool, the additional conditions are well-tailored to the Colombian context and must be retained. Oil pipeline The supplemental appropriations request also would provide Colombia with $6 million in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) assistance to begin training military units to protect the Caño Limón-Coveñas pipeline in northeastern Colombia. FARC and ELN guerrillas attacked the pipeline – whose oil belongs to a joint venture involving U.S.-based Occidental Petroleum – 170 times in 2001. The administration's 2003 Foreign Operations Appropriations request includes another $98 million in FMF for pipeline protection. This aid includes helicopters, training and equipment for Colombia's 18th Brigade, based in Arauca department on the Venezuelan border, and a new 5th Mobile Brigade. The $6 million in the supplemental merely seeks to "jump-start" this larger aid program. The proposal raises questions about whether the additional assistance, which will include $60 million for helicopters, will be able to bring an end to guerrilla attacks on the 400-mile-long pipeline. The guerrillas may adapt and begin to concentrate their attacks beyond the 18th Brigade’s jurisdiction (about the first 75 miles of the pipeline). If this happens, it is likely that Congress will be asked to provide still more FMF to protect the pipeline. Even in this one area there is plenty of room for escalation. But the pipeline is just one strategic element, in one corner of Colombia. U.S. Ambassador Anne Patterson told Colombia’s El Tiempo newspaper in February, “There are more than 300 infrastructure sites that are strategic for the United States in Colombia.”[15] Under the banner of infrastructure protection, then, there is plenty of room for escalated involvement. It is not clear why the administration has chosen to favor the Caño Limón pipeline over all others, though subsidizing the security costs of a U.S. corporation could be a motive. The “Critical Infrastructure Brigade,” as the Bush administration aid proposals call it, would be protecting a pipeline that, when operational, pumps about 35 million barrels per year. This adds up to $3 per barrel in costs to U.S. taxpayers to protect a pipeline for which Occidental currently pays security costs of about 50 cents per barrel, according to the Wall Street Journal.[16] Meanwhile, since December 2001, the AUC’s “Eastern Plains Bloc” has moved north from Casanare department and begun systematically killing people in two towns it has taken control of about 100 miles to the southeast of the pipeline. (See figure 3, the map at the end of this document.) It is worth keeping an eye on the 18th Brigade’s response, if any, to the paramilitary offensive in the towns of Tame and Cravo Norte, Arauca. If there is no effort to respond, we may be seeing a preview of a very ugly situation to come as the paramilitaries move further north to the pipeline zone. DOD vs. State As noted in the April 7 Washington Post, some provisions in the supplemental appropriations request would allow the Defense Department to provide $130 million in defense articles, services and training “in furtherance of the global war on terrorism, on such terms and conditions as the Secretary of Defense may determine.” At least since passage of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195, beginning with 22 USC 2151), Congress has determined that military aid be managed by the State Department and funded through the Foreign Operations appropriation. (The main exception has been Section 1004 of the 1991 National Defense Authorization Act [P.L. 101-510], which allows the Pentagon to provide military aid for counter-narcotics.) Allowing the Defense Department to provide “defense articles, services and training” to other countries through its own budget would call into question this long-standing arrangement. Why does the terrorist threat require that aid be given outside the framework of the Foreign Assistance Act? Indeed, why do we have a Foreign Assistance Act if so much aid is being delivered under another authority? Programs like Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and International Military Education and Training (IMET) already exist to grant defense articles, services and training to other countries. These programs are directed by the State Department and overseen by both houses’ Foreign Operations Appropriations subcommittees. It is not clear why the administration’s request excludes the State Department and the subcommittees. Is minimizing oversight a motive? Conclusion While we welcome the implicit recognition that Colombia’s problems go beyond narcotics, we are concerned about intensifying our overwhelmingly military approach. Instead of embarking on what may be a long and painful counter-insurgency commitment, we must realize that Colombia’s guerrillas, however barbaric their actions, are ultimately just a symptom of their country’s deeper historic social and economic problems. Defeating the FARC without attacking these problems will do nothing to stop a future resurgence of equally brutal violence. It is unlikely that a predominantly military approach can bring the security, governability and reform needed for a stable democracy to flourish in Colombia. Since the country is simply too large for the armed forces ever to maintain a permanent presence in all of its territory, military aid must be seen as a small piece of a much bigger puzzle. Not until Colombians are made to feel like stakeholders in a system managed by an accountable, responsive state will insurgency and criminality stop looking like attractive options. A true “counter-terror” approach to Colombia would be only partly military. Among other things, the bulk of our aid must support the civilian part of Colombia’s state, provide humanitarian aid to the displaced, help alleviate the economic desperation of Colombia’s countryside, and protect human rights and anti-corruption reformers both inside and outside of government. At the same time, the full weight of our diplomacy must support all efforts to get peace talks restarted with the FARC and to facilitate a cease-fire agreement with the ELN. While there is a role for Colombia’s military, the international community must focus more strongly on professionalizing and strengthening Colombia’s civilian state institutions. This could be made possible by increasing international support for peace negotiators, judges and prosecutors, human rights and anti-corruption activists, honest legislators, reformist police and military officers, muckraking journalists, and others who want to build a real, functioning democracy. Alternative development, infrastructure programs, and other state investment can create the conditions for a functioning legal economy in neglected rural areas. Drug-consuming countries must spend more money at home on efforts to reduce demand, which most studies indicate is most effectively achieved by offering treatment to addicts. Our aid must seek to alleviate – not worsen – the insecurity, poverty and injustice that feed Colombia’s violence. An overly militarized “sledgehammer” approach may only make the situation worse. Thank you very much. Figure 1. Andean Coca Cultivation

Table 1. All aid to Colombia since 19971a. Economic and Social Programs

1b. Military and Police Aid Programs

(Millions of dollars. Estimates, derived by averaging two previous years, are in italics. For links to source materials, see http://ciponline.org/facts/co.htm) Table 2. Colombia’s illegal armed groups

Figure 2. Tax collection in selected countries

Figure 3. Map of Arauca, Colombia

[1] White House Office of Management and Budget, Emergency Supplemental Appropriations request to Congress, March 20, 2002 <http://w3.access.gpo.gov/usbudget/fy2003/pdf/5usattack.pdf>. [2] Gabriel Marcella (U.S. Army War College), “The U.S. Engagement with Colombia: Legitimate State Authority and Human Rights,” North-South Center (University of Miami), March 2002 <http://www.miami.edu/nsc/pages/pub-ap-pdf/55AP.pdf>. [3] Gabriel Marcella, “Colombia’s Three Wars: U.S. Strategy at the Crossroads,” U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, March 5, 1999 <http://carlisle-www.army.mil/usassi/ssipubs/pubs99/3wars/3wars.pdf>. [4] World Bank, World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Poverty, (Washington: World Bank Group, October 2000): 282 <http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/wdrpoverty/report/tab5.pdf>. Norwegian Refugee

Council Global IDP Project, “The issue of land plays an intimate role

with the phenomenon of displacement,” (Oslo: IDP Project, 1999) <http://www.db.idpproject.org/Sites/IdpProjectDb/ [5] Marcella, “The U.S. Engagement with Colombia: Legitimate State Authority and Human Rights,” op. cit. [6] The World Bank, “Table 14. Central Government Finances,” World Development Report 2000/2001 (Washington: World Bank Group, 2000): 300 <http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/wdrpoverty/report/tab14.pdf>. Paul Krugman, “Ban the Bonds,” The New York Times, October 24, 2001 (Reproduced online at http://www.pkarchive.org/column/102401.html). [7] Government of Colombia, Ministry of Defense, "Es

necesario aumentar el gasto en defensa y seguridad nacional, sostiene

Ministro de Defensa," (Bogotá: SIDEN, March 11, 2002) <http://www.mindefensa.gov.co/politica/intervenciones/pdinterv20020311minbell_radio.html> [8] Transparency International, “New index highlights worldwide corruption crisis,” June 27, 2001 <http://www.transparency.org/cpi/2001/cpi2001.html>. [9] Gabriel Marcella, Charles E. Wilhelm, Alvaro Valencia Tovar, Ricardo Arias Calderon, and Chris Marquis, "Plan Colombia: Some Differing Perspectives," (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College), June 2001 <http://carlisle-www.army.mil/usassi/ssipubs/pubs2001/pcdiffer/pcdiffer.htm>. [10] Angel Rabasa and Peter Chalk, “Colombian Labyrinth: The Synergy of Drugs and Insurgency and Its Implications for Regional Stability,” Rand Corporation, June 2001 <http://www.rand.org/publications/MR/MR1339/>. [11] U.S. Department of State, “Colombia,” Country Reports on Human Rights Practices (Washington: Department of State, March 2002): <http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2001/wha/8326.htm>. [12] United Nations, High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Advance Edited Version: Informe de la Alta Comisionada de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos sobre la situación de los derechos humanos en Colombia” (Geneva: March 13, 2002): <http://www.unhchr.ch/pdf/17AV.pdf>. [13] “Colombian death squad leader reveals his face,” CNN International, March 2, 2000 <http://www.cnn.com/2000/WORLD/americas/03/02/colombia.fugitive/>. [14] Campaign of Alvaro Uribe Vélez, “Propuesta Programática: Un millón de colombianos colaborando de manera transparente con la Fuerza Pública, capacitados para actuar en solución pacífica de conflictos y como promotores de DDHH” (Bogotá: document obtained April 2002). [15] Clara Inés Rueda G., Interview with Ambassador Anne Patterson, El Tiempo (Bogotá, Colombia: February 10, 2002): <http://eltiempo.terra.com.co/10-02-2002/prip169177.html>. [16] Alexei Barrionuevo and Thaddeus Herrick, “Threat of Terror Abroad Isn't New For Oil Companies Like Occidental,” The Wall Street Journal (New York: February 6, 2002). |

|

|

| Asia | | |

Colombia | | |

| |

Financial Flows | | |

National Security | | |

| Center

for International Policy |