IPR:

"The New Masters of Barranca"

Copies

of this report are available for $1.50 each, or 50 cents each for orders

of 20 or more, from the Center for International Policy. Request copies

by e-mail at cip@ciponline.org.

This

report is also available in Adobe Acrobat (.pdf)

format

(403 KB).

"The

New Masters of Barranca"

A Report

from CIP’s trip to Barrancabermeja, Colombia, March 6-8, 2001

By Adam

Isacson

Yolanda

Becerra, an easygoing, dignified woman of perhaps fifty years, is

cheerfully patient with gringos who come to her office asking naive

questions. She hardly resembles a "military target," whatever

that means. But the paramilitary thugs who took over her city a few

months ago remind her regularly that she is in their sights.

|

|

The

Cristo Petrolero, or Christ of the Oilfields, rises out of the

swamp next to Barrancabermeja’s refinery.

|

Ms. Becerra

heads the Popular Women’s Organization (OFP), a group that provides

food, health services, job training, and legal aid through "women’s

houses" (casas de la mujer) in the working class

neighborhoods of Barrancabermeja, the main city in the Magdalena Medio

region of central Colombia. She looks tired, like she has not had

a good night’s sleep in quite a while. I doubt she has, because

the OFP has faced the worst of the paramilitaries’ brutal campaign

to clear away the remnants of the city’s once-vibrant civil society.

Barrancabermeja

is hard to pronounce, and very little of last year’s billion-dollar

package of U.S. military aid for Colombia will end up anywhere near

this city. But as Washington edges closer to Colombia’s long,

bloody conflict, "Barranca" offers a preview of the nightmare

to come. For the first time here, the war is entering a scary new

phase of urban fighting that may soon appear in Colombia’s larger

cities. It is being spearheaded by the paramilitaries, whose growing

power the United States can no longer afford to ignore. The only force

left standing in their way is a beleaguered but outspoken group of

independent, non-violent human rights groups and community leaders

like Ms. Becerra.

An "outlaw

city"

Put together,

the Spanish words "barranca" and "bermeja" mean

"reddish-colored ravine." I did not see any such natural

highlights during CIP’s March 6-8 trip there. But what one can

see, from almost everywhere one stands, is a massive oil refinery,

its 200-foot flare stacks belching flame and thick smoke twenty-four

hours a day. Sulfurous smells and industrial-sounding noises can be

perceived from a mile away.

Today,

about three-quarters of Colombia’s fuel comes from Barrancabermeja,

making it a strategically crucial city. Add its central location along

the country’s main roads, its port with access to the Atlantic,

the nearby presence of gold and mineral wealth, and its position along

drug-transit routes, and it becomes clear why Barrancabermeja would

be a difficult place for a country to govern while at war with itself.

Barranca

was considered an "outlaw city" well before today’s

guerrilla and paramilitary groups came on the scene. In 1916, when

the first oil well was drilled, it was a small fishing port on the

Magdalena River, Colombia’s 965-mile-long equivalent of the Mississippi.

But oil made this stiflingly hot settlement a boomtown for decades,

attracting thousands of job-seekers. Until about the 1950s, male oil

workers made up most of Barranca’s population, and many of the

few women were prostitutes brought in from all over the world.

People

kept coming, lured by the promise of jobs and forced out of the countryside

by violence. The  town’s

population exploded from 15,400 in the 1938 census to about 300,000

today. More than 80 percent of the city was formed by "land invasions"

– squatters’ settlements, basically – which evolved

into working-class neighborhoods on the eastern side of town, away

from the riverfront. The names of many neighborhoods are simply dates

(20 de enero, 25 de agosto, etc.), indicating the anniversaries of

their original "invasions." town’s

population exploded from 15,400 in the 1938 census to about 300,000

today. More than 80 percent of the city was formed by "land invasions"

– squatters’ settlements, basically – which evolved

into working-class neighborhoods on the eastern side of town, away

from the riverfront. The names of many neighborhoods are simply dates

(20 de enero, 25 de agosto, etc.), indicating the anniversaries of

their original "invasions."

Like

fast-growing industrial cities anywhere, Barrancabermeja has long

been a hotbed of labor activism, radical populist politics, corruption

and violence. Oil workers formed what is still one of the country’s

largest and most powerful labor unions (the Unión Sindical Obrera,

or USO), which over the years has lost dozens of its leaders and militants

to violence, much of it state-sponsored. Newly invaded neighborhoods

organized to press the government for basic services, often inviting

a harsh response. Repression in turn fed the development of sophisticated

local human rights organizations.

Inevitably,

this mix of strategic importance, ungovernability and leftist political

leanings attracted  Colombia’s

guerrilla groups. By the early 1970s the city was a stronghold of

the National Liberation Army (ELN), the country’s second-largest

Marxist guerrilla organization, whose urban militias held sway in

the eastern slums. The larger Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces

(FARC) arrived in the early 1990s, and a tiny third group, the vestigial

Popular Liberation Army (EPL), has also exercised influence. A visitor

can read slogans for all three spray-painted on walls throughout the

city, a rare sight in central Bogotá or Medellín. Abandoned by the

Colombian government, most residents of Barranca’s guerrilla-controlled

neighborhoods developed a live-and-let live approach, allowing the

leftist groups to operate in the open, paying "taxes" on

demand, and providing assistance when asked or forced to do so. Colombia’s

guerrilla groups. By the early 1970s the city was a stronghold of

the National Liberation Army (ELN), the country’s second-largest

Marxist guerrilla organization, whose urban militias held sway in

the eastern slums. The larger Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces

(FARC) arrived in the early 1990s, and a tiny third group, the vestigial

Popular Liberation Army (EPL), has also exercised influence. A visitor

can read slogans for all three spray-painted on walls throughout the

city, a rare sight in central Bogotá or Medellín. Abandoned by the

Colombian government, most residents of Barranca’s guerrilla-controlled

neighborhoods developed a live-and-let live approach, allowing the

leftist groups to operate in the open, paying "taxes" on

demand, and providing assistance when asked or forced to do so.

But the

guerrillas are just one entry on the city’s list of violent groups.

Major Agustín Rodríguez, a 34-year-old officer who commands the Colombian

Navy’s 61st Advanced Riverine Post, had a very long list. Maj.

Rodríguez – whose unit, which must patrol 300 miles of the Magdalena

River, is to my knowledge the only security force in the area that

receives U.S. assistance – told us about the ever-present guerrillas

and paramilitaries; the criminal gangs who operate freely; the narcotraffickers

who smuggle drugs made elsewhere and grow coca plants across the river

in southern Bolívar department, mainly in paramilitary-controlled

zones; a copper cartel that controls the products of the region’s

mines; and a gasoline cartel that steals up to a quarter of the refinery’s

product by punching holes in the pipeline, filling everything from

cans to tank trucks. Some refer to the pipeline as "the flute"

because of all the holes punched in it. Much of the gas cartel’s

product goes to the southern Bolívar coca fields, where it is used

in the process that turns the leaves into coca paste, and later cocaine.

The

paramilitaries’ quick conquest of the Magdalena Medio

Doodling visual aids on a piece of paper as he talked (my favorites

were the stick figures representing guerrillas and paramilitaries),

Maj. Rodríguez candidly acknowledged that the paramilitaries are right

now the strongest and the fastest growing of all the armed groups in

Barranca and the Magdalena Medio region. The United Self-Defense Groups

of Colombia (AUC), a gathering of anti-guerrilla militias privately

financed by landowners and narcotraffickers, clearly has the momentum

in Barranca and its environs. Headed by a 35-year-old former drug-cartel

associate named Carlos Castaño, the AUC now controls nearly all town

centers and many rural areas in all twenty-seven municipalities (counties)

of the Magdalena Medio.

The AUC’s

takeover happened very quickly. While rightist groups have been active

in the region since a death squad called Muerte a Secuestradores (MAS,

or "Death to Kidnappers") formed in 1981, these squads of

hit men did the guerrillas little damage during the 1980s, choosing

instead to target local civilian leaders, particularly labor organizers.

This began to change in the early 1990s, when local death squads were

integrated into a Colombian Navy intelligence network that killed

over 130 union officials, journalists, teachers, human rights defenders

and activists. [See

Human Rights Watch’s 1996 report, "Colombia’s Killer

Networks," on the Internet at www.hrw.org/reports/1996/killertoc.htm.]

|

|

A

panorama of central Barrancabermeja. The Magdalena River is

in the background.

|

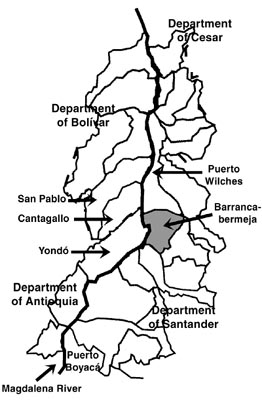

In 1993

the "paras" made the transition from hit-and-run death squads

to an occupying force, establishing their first permanent presence

in the Magdalena Medio region in the town of Puerto Boyacá. From there,

the newly formed AUC gained ground quickly through a strategy often

called "draining the sea to kill the fish" – a brutal

campaign of massacres, disappearances and forced displacement of the

civilian population. Paramilitary-controlled areas spread across the

map of the Magdalena Medio like a stain. Paramilitary terror in the

countryside sent a flood of refugees into Barrancabermeja,

swelling the city’s eastern zones and pushing the unemployment

rate to an estimated 50 percent by early 2001. By the end of the 1990s

the AUC had weakened the ELN so severely that paramilitaries controlled

even the guerrilla group’s mid-1960s birthplace in the San Lucas

Mountains of southern Bolívar department.

Colombian

and international human rights groups have thoroughly documented the

military support and toleration that eased the paramilitary takeover

of the Magdalena Medio. The relationship included the intelligence

networks of the early 1990s; sharing of information, weapons and ammunition;

failure to respond to paramilitary attacks and massacres; and willful

blindness to a very open AUC presence. The relationship continues

today; during our trip, CIP heard numerous complaints about activities

in the region around Barranca, including regular paramilitary checkpoints

100 meters from the 45th battalion’s headquarters across the

river in Yondó; paramilitary searches within 200 meters of the police

station in the port of Puerto Wilches, the next town downriver from

Barranca; and a regular 8 AM to 4 PM paramilitary river checkpoint

at a site called La Rompira, a few minutes north of Barranca, where

the paramilitaries kidnapped or disappeared eighteen people in 2000.

(The Navy told us that the paramilitaries do not maintain river checkpoints,

though on one recent occasion they found paramilitaries fleeing from

a site where one such roadblock had been reported.)

May

1998: The paramilitaries enter Barrancabermeja

By the

late 1990s, Barrancabermeja was the only population center in the

Magdalena Medio region without a permanent paramilitary presence.

In fact, the city was one of only a few breaks in a continuous band

of paramilitary control stretching across northern Colombia from Panama

in the west to Venezuela in the east.

|

|

Civil-military

operation: Colombia’s Army has set up a circus on the site

of the 1998 massacre

|

The first

major paramilitary incursion in the city took place on May 16, 1998.

In one night of terror, paramilitaries swept through several of the

city’s eastern ELN-controlled neighborhoods, killing eleven people

and taking away another twenty-five whom they killed later. The 1998

massacre signaled the paramilitaries’ transition from selective

killings to full-scale military actions within Barrancabermeja’s

city limits. Many residents consider the May 1998 massacre a watershed

moment for control of the city; one human rights activist said that

Barranca’s history could be divided between a pre-1998 period

and a post-1998 period. [See

Amnesty International’s 1999 report, "Barrancabermeja: a

City under Siege," on the Internet at http://www.amnesty.org/ailib/aipub/1999/AMR/22303699.htm.]

After

May 1998, the AUC presence in Barranca slowly increased, as massacres

and other larger-scale activities became frighteningly common. For

a time, though, the paramilitaries focused more strongly on other

parts of Colombia (such as southern Bolívar department and the Catatumbo

region near Venezuela, where massacres took place almost daily in

1999). Though their incursions were more frequent, the AUC still lacked

the regular presence in Barrancabermeja that would make them a true

occupying force.

The

final paramilitary push into Barrancabermeja

This

began to change in April 2000, when a twenty-something deputy of Carlos

Castaño’s named "Julián" made a radio announcement

declaring his presence in Barranca and the AUC’s determination

to take over the city. A terrifying upsurge in violence followed;

in 2000, the government’s regional Human Rights Ombudsman’s

office reported, 539 people were killed in Barrancabermeja –

about 25 times the murder rate of New York City. Eighty-seven percent

were victims of the paramilitaries.

|

|

Carlos

Castaño

|

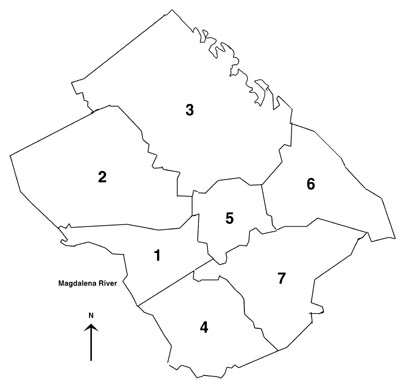

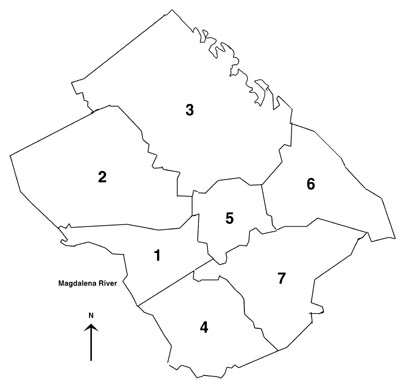

In late

December 2000, the paramilitary offensive began in earnest. Starting

in the east-central neighborhoods of Miraflores and Simón Bolívar,

more than 1,000 paramilitaries spread throughout the eastern half

of Barrancabermeja, and this time they stayed. Taking over neighborhood

after neighborhood, they gained control of most of the city in about

two months. When CIP staff came to visit in early March, only about

one and a half of the city’s seven "comunas," or wards

– essentially, just the downtown and the area around the oil

refinery – were outside of the AUC’s dominion. A frequently

repeated rumor was that Carlos Castaño himself had paid a brief visit

to Barranca’s formerly ELN-held northeast at the end of December,

fulfilling a boast that he would "have a cup of coffee"

there by New Year’s Day 2001.

|

|

Barranca

and its comunas (wards): By most accounts, as of early March

the paramilitaries had taken all but comuna 2 and part of comuna

1

|

The paramilitary

offensive began immediately after a series of Colombian government

meetings with ELN leaders in Cuba. At these talks, the government

showed itself willing to ease negotiations by pulling security forces

temporarily out of two municipalities (counties) across the river

from Barrancabermeja. The municipalities, San Pablo and Cantagallo

in Bolívar department, had passed from ELN to paramilitary control

during the previous two years. While the government’s decision

was no doubt unpopular – a similar demilitarized zone granted

to the FARC has been the site of numerous abuses, with little progress

after two years of talks – the paramilitaries encouraged protests

against the zone (at times by force), including mid-February demonstrations

during which 13,000 protestors closed key roads for days.

So

far, the rule of what one human rights leader called "the new

masters of Barranca" has been exceedingly cruel. According to

the Technical Investigations Unit of Colombia’s Attorney-General’s

office, the AUC killed 145 people in Barranca during the first forty-five

days of 2001. Of these, estimates Ms. Becerra’s Popular Women’s

Organization (OFP), 15 percent were women.

In addition

to mass killing, the paramilitaries maintain control by closely supervising

all activity in their newly conquered neighborhoods. Residents of

the Barrio Kennedy sector, which was being used as a center of AUC

operations during CIP’s early March visit, are required to keep

their doors open day and night so that paramilitaries can enter and

leave at will. Paramilitary fighters are forcing some families out

of their homes (in Barrio Kennedy in February, they gave the families

a half-hour of prior notice), then using the houses as barracks and

headquarters. The paramilitaries have cut phone lines into several

neighborhoods, and they stop everyone in the street to interrogate

them about their destination and their business. Many people have

not left their neighborhoods in months. Because of Barranca’s

daily high-90-degree heat, people are accustomed to sitting and walking

outside in the cool of the evening – but in the paramilitary-controlled

neighborhoods, the frightened residents stay inside.

Local

human rights leaders told us that the paramilitaries are actively

recruiting 17- to 19-year-old boys, many of them veterans of the ELN

militias, and offering them a salary, one month’s pay up front,

a bicycle and perhaps a cell phone. The new recruits’ job is

to "clean" their neighborhoods of guerrilla supporters.

"While these boys may have been in the militias before, even

their own families fear them now," one community leader told

us. When these boys are no longer useful, we were told, the paramilitaries

kill them because they know too much – a practice called "erasing

information."

In

response to numerous calls for a government response, the security

forces have militarized parts of the city. Heavily armed soldiers

watched us from street corners, and we saw police mini-tanks parked

at the entrances to some conflictive neighborhoods. In January, Bogotá

pledged to send 1,000 Colombian Army special forces to keep order,

though the mayor, the bishop, and non-governmental organizations protested

that the deployment would only add to the violence. To date, only

eighty have arrived. January 12 marked the arrival in the city of

the so-called "Robocops" – an elite police unit easily

recognizable by their black uniforms, wrap-around sunglasses, and

wide array of weapons. The Robocops and other measures have made little

difference, though: between January 12 and early March, the number

of dead in the current paramilitary offensive tripled and the AUC

took over three of the city’s seven wards.

The presence

of police, however infrequent, in the "hot" neighborhoods

has not in the least bit hindered the paramilitaries. CIP President

Robert White and I saw plenty of them operating openly in Barrancabermeja’s

eastern neighborhoods during a tour organized by the Popular Women’s

Organization. Though they quickly removed their AUC armbands as our

bus entered neighborhoods like Barrio Kennedy, even the most clueless

gringo could identify the men wearing polo shirts, slacks and two

cell phones on their belts, standing idly on the sides of streets

lined with houses made of scrap wood, cinder blocks and corrugated

metal. The young men following us on motor-scooters and bicycles –

especially the angry-looking individual staring us down as he rode

circles around our slow-moving bus – were unmistakable. It was

clear who "the new masters of Barranca" were.

Looking

for explanations

How,

we found ourselves asking everyone we met, did they do it so fast?

Why did it take the paramilitaries little more than two months to

take over a longtime guerrilla stronghold?

The answer

we heard most often was not surprising, given the recent history of

the Magdalena Medio: the paramilitaries took over Barrancabermeja

so quickly thanks to the complicity and cooperation of Colombia’s

security forces. The AUC invasion began on December 23, coinciding

with a military operation known as "Operation Merry Christmas."

With the stated goal of guaranteeing a peaceful Christmas holiday,

military and police units set up a temporary presence in the entire

city. At the same time, hundreds of paramilitary fighters fanned out

into key neighborhoods. When the security forces withdrew, the paramilitaries

stayed behind, and the killings began.

Though

fear has silenced most witnesses to military-paramilitary collaboration

during the current offensive, CIP heard numerous accounts of military

and paramilitary personnel operating separately but in full view of

each other, of police officers sharing cell phones with paramilitaries

and transporting them in their mini-tanks, and of paramilitaries being

warned well in advance of impending "raids" on their bases

of operations in the eastern neighborhoods. We heard an account of

police catching paramilitaries in the act of breaking into a house,

and instead of arresting them telling them to go away "because

it could cause trouble for us in Bogotá." We were told that while

a January 29 raid brought the arrests of fourteen paramilitaries,

eleven were inexplicably set free the following day. Though

fear has silenced most witnesses to military-paramilitary collaboration

during the current offensive, CIP heard numerous accounts of military

and paramilitary personnel operating separately but in full view of

each other, of police officers sharing cell phones with paramilitaries

and transporting them in their mini-tanks, and of paramilitaries being

warned well in advance of impending "raids" on their bases

of operations in the eastern neighborhoods. We heard an account of

police catching paramilitaries in the act of breaking into a house,

and instead of arresting them telling them to go away "because

it could cause trouble for us in Bogotá." We were told that while

a January 29 raid brought the arrests of fourteen paramilitaries,

eleven were inexplicably set free the following day.

While

the security forces’ cooperation made the paramilitaries’

rapid takeover possible, the guerrillas who controlled Barranca’s

working-class neighborhoods clearly played a role in their own defeat.

Pushed by threats or lured by the promise of higher pay, many members

of the ELN’s urban militias switched sides. These new AUC cadres

brought with them their lists of former guerrilla contacts, which

(along with the names of anyone else even rumored to be guerrilla

supporters) formed the hitlists for the paramilitaries’ killing

sprees.

The region’s

military commander, Fifth Brigade chief Gen. Martín Orlando Carreño,

places all the blame for the city’s takeover on the guerrillas.

"It’s all the guerrillas’ fault. They pushed the people

into the paramilitaries’ hands."

(Gen.

Carreño – whose predecessor at the Fifth Brigade was fired for

allowing paramilitary massacres in the Catatumbo region – is

a politically savvy officer and a likely future head of the military.

He is also a 1990 graduate of the School of the Americas’ year-long

Command and General Staff course.)

Certainly,

many of the city’s exhausted residents probably do welcome the

relative peace that comes with living in a zone under one group’s

undisputed control. César, my cab driver, was no exception. One evening

he accompanied me down to the riverbank near my hotel. Fishermen were

just loading up their long, narrow canoes for a night of casting nets,

and several people with trucks and wheelbarrows were shoveling river

sand through screens, hauling it away for construction material. Once

we were out of hearing, César stopped talking about fishing. "I

don’t support the paramilitaries and I don’t want to have

anything to do with them. But the ELN were abusing everyone in the

neighborhoods, and now that the paras are in charge things are better.

At least things are calm." This calm is only superficial, though;

Gen. Carreño noted that in many areas the paramilitaries are going

too far, mistreating the local population and winning only fear, not

support.

A

coming escalation?

The outlook

for the near future is even darker. By many accounts, the FARC and

ELN are teaming up for a counteroffensive, threatening a further escalation

in urban violence. Instead of responding  directly

to Plan Colombia in the southern department of Putumayo, many believe

that the FARC is shifting to other conflict zones like the Magdalena

Medio, a move that also gives the larger group an opportunity to fill

the vacuum left by the clearly declining ELN. During our visit we

heard reports of open firefights and house-to-house warfare on the

streets of Barranca’s eastern neighborhoods in the previous few

days, apparently between paramilitaries and the jointly operating

guerrillas. directly

to Plan Colombia in the southern department of Putumayo, many believe

that the FARC is shifting to other conflict zones like the Magdalena

Medio, a move that also gives the larger group an opportunity to fill

the vacuum left by the clearly declining ELN. During our visit we

heard reports of open firefights and house-to-house warfare on the

streets of Barranca’s eastern neighborhoods in the previous few

days, apparently between paramilitaries and the jointly operating

guerrillas.

Meanwhile,

across the river in southern Bolívar department, the Colombian army

was mounting a rare offensive. According to Gen. Carreño, the mission

of "Operation Bolívar" is to regain government control and

eliminate coca cultivation from the zone that may become the site

of the ELN peace negotiations. During the first four weeks of this

operation, ten U.S.-supplied Turbo Thrush spray aircraft fumigated

3,600 hectares (about 9,000 acres) of coca with the chemical glyphosate.

(These were the same spray planes used from December through February

for the first phase of the "Plan Colombia" offensive, far

to the south in Putumayo department.) Details about the operation’s

targets have been sketchy, though authorities claim that the paramilitaries

have been hardest hit by the military engagements and the fumigation.

Several times we heard mention of a January raid on a paramilitary

headquarters at San Blas, Bolívar department – though the paramilitaries,

obviously warned in advance, had abandoned the site well before the

raid. The ELN, which on March 9 broke off contacts with the Colombian

government to protest Operation Bolívar, apparently sees itself, and

not the paramilitaries, as the offensive’s main target.

Barranca’s

besieged community leaders

Amazingly,

despite its growing violence and bleak outlook, Barrancabermeja still

has a vibrant, outspoken civil society. After years of repression

and selective assassination, the remnant of Barranca’s labor

unions and popular movements remains mobilized and defiant.

Most

of the city’s neighborhood associations, women’s groups,

and human rights groups never had a friendly relationship with the

ELN. But at least, the Popular Women’s Organization (OFP) told

us, when they protested mistreatment the guerrillas generally left

them alone. "The ELN never liked us but they never blocked our

work," explained one of the group’s leaders.

|

|

CIP

President Robert White with the OFP’s Matilde Vargas (standing)

|

Things

are far worse now. At this point, Barranca’s civil-society groups

are just about the only people the AUC does not control in the eastern

neighborhoods. Declaring them "military targets," the paramilitaries

are carrying out a campaign of constant threats and intimidation against

the few organizations that remain vocally opposed to them.

The entire

board of directors of the Regional Human Rights Committee (CREDHOS,

which has lost many members to selective killings) has been threatened

within the past few months; three have left Barranca since last September

and two have survived assassination attempts. The Association of Relatives

of the Disappeared (ASFADDES), which includes many families of victims

and witnesses of the May 1998 massacre, was forced to close its Barrancabermeja

office on February 28, 2001. The USO oil workers’ union has scaled

back its political activities in the last few months.

Government

agencies and international organizations have also faced paramilitary

aggression. The Colombian government’s Social Solidarity Network,

which provides aid to internally displaced persons, and regional Human

Rights Ombudsman’s office admit that they are largely unable

to work in Barrancabermeja’s eastern neighborhoods. On March

1, paramilitaries detained for hours and stole all supplies from an

international humanitarian mission delivering aid to a displaced community

in southern Bolívar department. The mission, with representatives

of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the World Food Program,

the government Human Rights Ombudsman, the Social Solidarity Network,

and the non-governmental Magdalena Medio Peace and Development Program,

was stopped for eight hours at a site only fifteen minutes from the

Colombian Army’s 45th Battalion headquarters.

Of all

agencies, Ms. Becerra’s OFP has been the most aggressively and

specifically targeted since the paramilitary takeover began. On January

27, paramilitaries paid two visits to the OFP’s "women’s

house" in southeastern Barrancabermeja, demanding that the house’s

director hand over the keys to the facility. This demand illustrates

the paramilitaries’ strategy, Ms. Becerra explained. The AUC

has no desire to shut down OFP’s food, health and other services,

which many of the neighborhood’s residents use regularly. Instead,

they want the OFP directors out of the way so that they can provide

the same services themselves – which is why they want the keys

to the "women’s houses." The second paramilitary visitor

to the OFP on January 27 was so belligerent that the police had to

come and arrest him. He was let go the following day.

|

|

Paramilitaries

want the keys to the OFP “women’s house” (casa

de la mujer) in southeastern Barrancabermeja

|

Most

of Barrancabermeja’s human rights defenders go everywhere these

days in the company of foreign volunteers wearing T-shirts from Peace

Brigades International (PBI), a non-profit organization that provides

"accompaniment" to threatened activists in several countries.

PBI has a long and successful record of protecting dissident voices

in some very threatening situations. Several Barranca civil-society

leaders credit PBI’s European, Canadian and U.S. observers with

making their work possible during the current paramilitary onslaught.

"Without their accompaniment, I couldn’t visit the neighborhoods

where we work," said one. Another admitted that PBI volunteers

even accompany her to the bathroom when in the affected neighborhoods,

"because you never know when they might come for you."

Yet even

PBI is facing a serious challenge in Barrancabermeja. On February

8, two paramilitary thugs came back to the OFP’s southeastern

Barranca "women’s house" demanding the keys. They took

away the cell phone and passport of a Swedish Peace Brigades observer

accompanying the house’s staff, and declared both the house’s

director and the PBI worker "military targets."

Perhaps

cowed by the international outcry they triggered, the paramilitaries

appeared to shift their strategy in late February, directing their

threats at the OFP’s social base instead of its leadership. Seeking

to dry up the group’s support, the rightists are spreading word

that they will target all women who participate in OFP-sponsored events

and activities. The strategy seems to be working. Ms. Becerra told

me that on November 24, 2000, the OFP held a street march that attracted

10,000 participants. Now, because of the threats against the neighborhoods’

women, she doubts that she can convene a thousand.

|

Some

of Barrancabermeja’s best-known human rights defenders

The

Popular Women’s Organization (Organización Femenina

Popular, or OFP)

The

OFP, a support organization for Barrancabermeja’s working-class

women, was founded by the Catholic Church in 1972. It became

autonomous from the church in 1988 and in 1995 expanded its

work elsewhere in the Magdalena Medio region. The OFP offers

many services to the region’s women: economic aid (inexpensive

kitchens, cooperatives, training), education (scholarships,

publications and teaching materials), health services, youth

services (music and dance workshops), assistance to displaced

persons, and legal aid for victims of human rights violations.

The

Association of Relatives of the Disappeared (ASFADDES)

ASFADDES

is a support network for those whose family members have been

forcibly disappeared (over 4,600 people have been "disappeared"

in Colombia since 1982). ASFADDES offers legal assistance, documentation,

accompaniment, education and economic assistance. It fights

for verdicts against the perpetrators and reparations for the

victims’ families. The association has offices in the Colombian

cities of Bogotá, Bucaramanga, Popayán, Neiva, and Medellín.

Under relentless paramilitary harassment, ASFADDES closed its

Barrancabermeja office on February 28, 2001.

The

Regional Corporation for the Defense of Human Rights (CREDHOS)

Founded

in 1988, CREDHOS has a 25-member directorate and a membership

of 500 activists who work to defend the human rights of the

residents of Barrancabermeja and the Magdalena Medio region.

CREDHOS carries out human rights education projects throughout

the city, receives and investigates denunciations of human rights

abuses, and provides legal aid and technical assistance to victims

of violations.

Magdalena

Medio Peace and Development Program (PDPMM)

Founded

in 1995 by the Center for Research and Public Education (CINEP)

and the Diocese of Barrancabermeja, this highly regarded, large-scale

program carries out development and conflict-resolution projects

in some of the most troubled parts of the Magdalena Medio Region.

Peace

Brigades International (PBI)

Since

1994, PBI has maintained a program in Colombia to protect human

rights defenders and communities of displaced persons. Following

a strictly non-violent methodology, Peace Brigades workers physically

accompany threatened people and organizations, perform periodic

visits to conflict zones and meet regularly with local authorities

and non-governmental organizations. Currently, PBI volunteers

come from at least twelve countries in North America and Europe.

The organization operates in Bogotá, the Magdalena Medio region,

Medellín, and the Urabá region in northwestern Colombia. In

the Magdalena Medio, PBI volunteers accompany the OFP, CREDHOS,

and ASFADDES.

(Source:

Government of Colombia, Defensoría del Pueblo, Resolución Defensorial

No. 007 [Bogotá: March 6, 2001]).

|

During

our visit, it became obvious that the paramilitaries had not completely

given up their intimidation of OFP leaders. On March 7, AUC members

entered an eastern Barranca "women’s house" and destroyed

literature promoting an OFP event commemorating International Women’s

Day (March 8). Later that same day, while attending a gathering to

prepare for the March 8 event, Ms. Becerra got a call on her cell

phone from a stranger telling her to "get ready for what’s

coming."

Protecting

human rights defenders

What

can be done to protect Barranca’s battered human rights groups

in such awful circumstances? We asked the city’s new mayor, Julio

César Ardila, a former human rights ombudsman whose low-budget campaign

defeated the powerful Liberal Party machine largely by plastering

his campaign logo – a 1970s-style smiley-face – all over

town. Mayor Ardila argued that a permanent military presence throughout

the city would force out the paramilitaries and make conditions safe

for community leaders. "People don’t trust the security

forces here because they only come for a little while and then they

leave. They never stay." Gen. Carreño agreed with this criticism,

blaming it on scarce resources. He added that one of his main goals

is to increase permanent military deployments throughout the region.

When

I asked their opinion about this proposal, Barrancabermeja’s

human rights and community leaders disagreed emphatically. Some laughed

out loud. Given the history of military-paramilitary collaboration

that continues today, they argued, a further militarization of Barranca

would guarantee their extermination rather than protect them. They

do not see Colombia’s state as a potential protector.

The city’s

civil society groups believe that only international support can allow

them to do their work amid the current paramilitary offensive. Specifically,

they are asking for two types of help from non-Colombians.

First,

they contend that international pressure makes a huge difference.

Statements of concern, communiqués, responses to urgent-action requests,

and messages from the U.S. government (including members of Congress)

– any indications that the international community is watching

closely – have strong effects that are widely felt in Barrancabermeja.

Second,

the city’s human rights groups call for what they call "accompaniment"

– the physical presence of international allies alongside them,

at their events, in their offices, even on the street. While the PBI

presence is essential, we were told, the groups also need regular

visits from their allies in North America and Europe. Given the obvious

security risk, it would be irresponsible for the Center for International

Policy to recommend that individual U.S. citizens go to Barrancabermeja.

We nonetheless encourage our counterpart organizations in the United

States and Europe, who have the contacts and can take the precautions

necessary to minimize risk, to consider complying with the accompaniment

requests of the city’s human rights defenders, preferably coordinating

with their networks to guarantee maximum coverage. We also pass along

the Barrancabermeja human rights community’s expressions of gratitude

to Minnesota Sen. Paul Wellstone, who has visited the city twice,

in November 2000 and March 2001.

A

long-term approach, if political will exists

International

pressure and visits are not long-term solutions, though. Untying Barrancabermeja’s

tangle of violence and instability – preferably before its experience

is repeated in other, larger Colombian cities – will require

Colombians to take national-level action. The United States must also

be prepared to offer important assistance at key moments.

First

and foremost, Colombia’s government needs to do much more to

stop the paramilitaries. Colombians will not trust their state to

protect them until all can agree that the military-paramilitary relationship

has been decisively broken. This means arresting known paramilitary

leaders and responding quickly to attacks and threats. It also means

punishing security force personnel who aid and abet paramilitaries

or who knowingly allow abuses to occur. The United States, which has

entered into a very close partnership with Colombia’s security

forces, must apply heavy public and private pressure for a greater

anti-paramilitary effort. One under-utilized channel might be the

denial of U.S. visas to individuals credibly alleged to be financially

supporting the rightist groups.

Even

though it is frustrating and may take years, Colombia’s peace

process needs greater support because it offers a quicker way out

of the violence than an escalated war of attrition. From military

officers to human rights workers, everyone we met with expressed a

belief that the ELN guerrillas honestly desire peace. If the government

stands up to the paramilitaries and temporarily grants a demilitarized

zone across the river, it may pave the way for the smaller rebel group’s

graceful exit. It may also provide an instructive example for the

FARC about the viability of entering into serious negotiations.

Finally,

it is quite remarkable that everyone with whom we spoke – from

the brigade to the barrio – agreed that Colombia does not need

another massive package of military aid from Washington. Conflictive

zones like Barrancabermeja and the Magdalena Medio need social and

economic assistance. Development aid can alleviate the economic desperation

that feeds the conflict, and it can increase Colombian citizens’

confidence in their own government’s ability to deliver the goods.

This assistance must not be imposed from above – it must be designed

in coordination with the recipient communities, and it must avoid

inadvertently strengthening the paramilitaries, who are already promoting

their own plan for developing the Magdalena Medio region.

I asked

several people to respond to the U.S. government’s oft-repeated

argument that development projects cannot work by themselves until

military aid first provides security conditions. Major Rodríguez,

the naval officer, had the snappiest response. "We’ve been

trying to provide security conditions for thirty years and it hasn’t

worked. Development projects need to start now, even if we have to

start small. If the projects are successful, they will create support

among the population, who will then support the government. That’s

the best way to weaken the armed groups. More arms will not solve

the problem."

There

is nothing particularly new or innovative about these proposed solutions.

What has been lacking in Bogotá and Washington is the political will

to take the risks required for these old proposals to become reality.

We are still waiting for credible and far-reaching efforts to stop

the paramilitaries, unequivocal support for peace negotiations, and

economic assistance programs instead of dramatic military offensives.

While

we wait, the OFP and their colleagues keep trying to do their work.

On our tour of Barrancabermeja’s paramilitary-controlled eastern

neighborhoods, OFP leaders took us to one of the public kitchens where

they sell inexpensive meals to the locals. From this hilly zone the

flames of the refinery were easily visible, miles away next to the

river. A young man followed our group and stood outside the door,

sizing us up. Everyone stopped talking.

"Good

morning," an OFP leader addressed him, looking him in the eye.

"Good

morning," he replied.

A pause.

"Can I help you with something?"

"Are

you serving lunch yet?" (Nice try – it was just after 10

o’clock in the morning.)

"No.

Please come back later."

The paramilitary

watcher sidled off, further down the street. The OFP leader launched

into her lecture, as though nothing had happened.

The Center

for International Policy wishes to thank the CarEth and Compton Foundations

and the Stuart Mott Charitable Trust for the financial support that

made our visit possible. We also give our sincerest thanks to the United

Nations Development Program’s Barrancabermeja Office for offering

us so much advice and assistance.

|

|

CIP

Senior Associate Adam Isacson (left) with CIP President Robert

White (right) in Barrancabermeja

|

Center

for International Policy

1755 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Suite 312

Washington, DC 20036

(202) 232-3317

Fax: (202) 232-3440

cip@ciponline.org

www.ciponline.org

A Publication of the Center for International Policy

©

Copyright 2001 by the Center for International Policy. All rights reserved.

Any material herein may be quoted without permission, with credit to

the Center for International Policy. The Center is a nonprofit educational

and research organization promoting a U.S. foreign policy based on international

cooperation, demilitarization and respect for basic human rights.

ISSN 0738-6508

|

town’s

population exploded from 15,400 in the 1938 census to about 300,000

today. More than 80 percent of the city was formed by "land invasions"

– squatters’ settlements, basically – which evolved

into working-class neighborhoods on the eastern side of town, away

from the riverfront. The names of many neighborhoods are simply dates

(20 de enero, 25 de agosto, etc.), indicating the anniversaries of

their original "invasions."

town’s

population exploded from 15,400 in the 1938 census to about 300,000

today. More than 80 percent of the city was formed by "land invasions"

– squatters’ settlements, basically – which evolved

into working-class neighborhoods on the eastern side of town, away

from the riverfront. The names of many neighborhoods are simply dates

(20 de enero, 25 de agosto, etc.), indicating the anniversaries of

their original "invasions." Colombia’s

guerrilla groups. By the early 1970s the city was a stronghold of

the National Liberation Army (ELN), the country’s second-largest

Marxist guerrilla organization, whose urban militias held sway in

the eastern slums. The larger Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces

(FARC) arrived in the early 1990s, and a tiny third group, the vestigial

Popular Liberation Army (EPL), has also exercised influence. A visitor

can read slogans for all three spray-painted on walls throughout the

city, a rare sight in central Bogotá or Medellín. Abandoned by the

Colombian government, most residents of Barranca’s guerrilla-controlled

neighborhoods developed a live-and-let live approach, allowing the

leftist groups to operate in the open, paying "taxes" on

demand, and providing assistance when asked or forced to do so.

Colombia’s

guerrilla groups. By the early 1970s the city was a stronghold of

the National Liberation Army (ELN), the country’s second-largest

Marxist guerrilla organization, whose urban militias held sway in

the eastern slums. The larger Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces

(FARC) arrived in the early 1990s, and a tiny third group, the vestigial

Popular Liberation Army (EPL), has also exercised influence. A visitor

can read slogans for all three spray-painted on walls throughout the

city, a rare sight in central Bogotá or Medellín. Abandoned by the

Colombian government, most residents of Barranca’s guerrilla-controlled

neighborhoods developed a live-and-let live approach, allowing the

leftist groups to operate in the open, paying "taxes" on

demand, and providing assistance when asked or forced to do so.

Though

fear has silenced most witnesses to military-paramilitary collaboration

during the current offensive, CIP heard numerous accounts of military

and paramilitary personnel operating separately but in full view of

each other, of police officers sharing cell phones with paramilitaries

and transporting them in their mini-tanks, and of paramilitaries being

warned well in advance of impending "raids" on their bases

of operations in the eastern neighborhoods. We heard an account of

police catching paramilitaries in the act of breaking into a house,

and instead of arresting them telling them to go away "because

it could cause trouble for us in Bogotá." We were told that while

a January 29 raid brought the arrests of fourteen paramilitaries,

eleven were inexplicably set free the following day.

Though

fear has silenced most witnesses to military-paramilitary collaboration

during the current offensive, CIP heard numerous accounts of military

and paramilitary personnel operating separately but in full view of

each other, of police officers sharing cell phones with paramilitaries

and transporting them in their mini-tanks, and of paramilitaries being

warned well in advance of impending "raids" on their bases

of operations in the eastern neighborhoods. We heard an account of

police catching paramilitaries in the act of breaking into a house,

and instead of arresting them telling them to go away "because

it could cause trouble for us in Bogotá." We were told that while

a January 29 raid brought the arrests of fourteen paramilitaries,

eleven were inexplicably set free the following day. directly

to Plan Colombia in the southern department of Putumayo, many believe

that the FARC is shifting to other conflict zones like the Magdalena

Medio, a move that also gives the larger group an opportunity to fill

the vacuum left by the clearly declining ELN. During our visit we

heard reports of open firefights and house-to-house warfare on the

streets of Barranca’s eastern neighborhoods in the previous few

days, apparently between paramilitaries and the jointly operating

guerrillas.

directly

to Plan Colombia in the southern department of Putumayo, many believe

that the FARC is shifting to other conflict zones like the Magdalena

Medio, a move that also gives the larger group an opportunity to fill

the vacuum left by the clearly declining ELN. During our visit we

heard reports of open firefights and house-to-house warfare on the

streets of Barranca’s eastern neighborhoods in the previous few

days, apparently between paramilitaries and the jointly operating

guerrillas.