IPR:

Plan Colombia’s

"Ground Zero"

Copies

of this report are available for $1.50 each, or 50 cents each for orders

of 20 or more, from the Center for International Policy. Request copies

by e-mail at cip@ciponline.org.

This

report is also available in Adobe Acrobat (.pdf)

format

(565 KB).

Plan

Colombia’s "Ground Zero"

A Report

from CIP’s trip to Putumayo, Colombia, March 9-12, 2001

By Adam

Isacson and Ingrid Vaicius

Ask longtime

residents what Putumayo was like more than twenty years ago, before

coca entered the picture, and they describe a place that sounds too

good to be true. A place with endless tracts of jungle teeming with

monkeys and butterflies. Rivers full of fish and rare pink freshwater

dolphins. Parrots and macaws flying above the treetops in the mornings

and evenings, in flocks so large they resembled colorful clouds.

|

|

Two

months after U.S.-funded fumigations, nothing grows in a field

where farmers had planted coca amid their bananas.

|

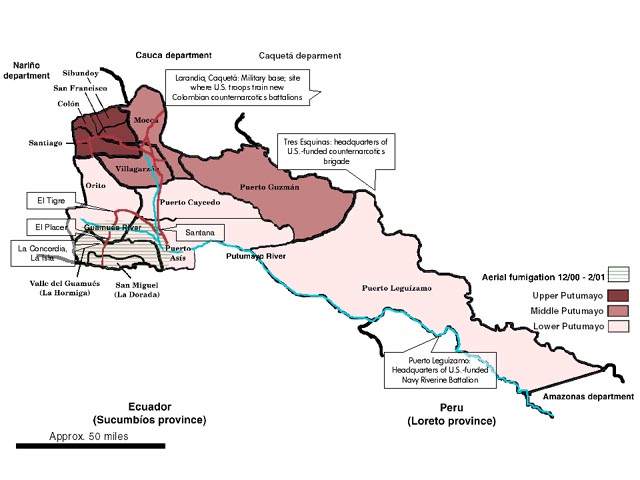

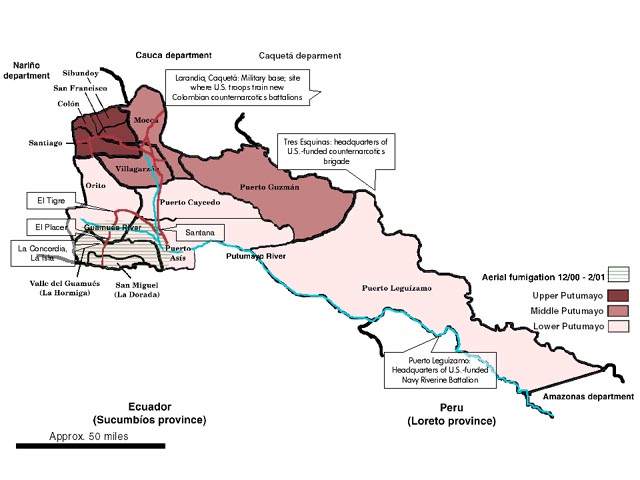

The department

(province) of Putumayo, in Colombia’s far south bordering Ecuador

and Peru, is a sliver of land about the size of the state of Maryland.

Its topography and climate vary from the cool Andean foothills in

the northwest (known as "upper Putumayo"), to a central

plateau of plains and savannah ("middle Putumayo"), to the

lush, steamy lowlands in the south and southeast ("lower Putumayo").

Following the course of the department’s many rivers from the

highlands to the lowlands, the locals use "up" and "down"

instead of compass points when giving directions. Though the muddy,

chocolate-brown Putumayo River begins only a couple of hundred miles

from the Pacific Ocean, a boat put in the water here can drift downstream

along the borders with Ecuador and Peru, into the Amazon river and,

eventually, into the Atlantic.

We saw

many remnants of the old Putumayo during CIP’s March 9-12 trip

there. It is still a beautiful place, overwhelming the eye with vivid

green. But we also saw forests knocked down to grow illegal crops,

armed groups operating freely, fields devastated by herbicides, and

widespread poverty and fear. We were strongly dismayed by the United

States’ role there, as Putumayo is the main destination of Washington’s

controversial plan to fumigate drug crops, supported by hundreds of

millions of dollars in mostly military aid.

We had

come to Putumayo to evaluate this program in the wake of its first

phase, an eight-week blitz of aerial herbicide spraying that had ended

one month earlier. The policy’s supporters call the U.S.-sponsored

effort a "balanced approach." But so far it has been purely

military, with not a dime spent yet on economic assistance programs

that might prevent farmers from moving and re-planting coca, the plant

used to make cocaine. We found that the zone where fumigations occurred

is dominated not by so-called "industrial" coca plantations,

but by families who are now running out of food. We found truth behind

claims that the spraying had negative health effects and destroyed

legal crops, including alternative development projects. We were disturbed

by evidence that the fumigations proceeded more smoothly because of

a paramilitary offensive in the zone to be sprayed. We found that

the people of Putumayo want to stop growing coca, and that they have

clear proposals for how U.S. assistance can help them make a living

legally.

Colombia’s

coca capital

Putumayo

began its downhill slide around 1979, when coca first appeared. Back

then the department had perhaps a third of the 300,000-plus people

it has today.

Though

a large indigenous population has deep roots, most Putumayo residents

are first or second-generation arrivals from somewhere else in Colombia.

Thousands have migrated over the past forty years from Colombia’s

historic population centers in the Andes and the coast, pushed out

by violence, attracted by the promise of land for the taking, or even

brought in by abortive government-run "directed colonization"

programs. Short-lived "bonanzas" based on a single product,

especially a rubber-tree boom in the 1960s and an oil boom in the

1970s, brought in floods of job-seekers until markets collapsed or

productive capacities were met. (Putumayo has significant oil reserves,

though production today is far from its late-1960s peak.)

|

Despite

Putumayo’s population explosion, the Bogotá government did little

to make its presence felt. Police, judges, hospitals, schools, banks,

and decent roads are very rare. Where they exist, electricity and

running water are very recent arrivals. Government neglect not only

brought a lawless "wild west" atmosphere, it also made it

virtually impossible to make a living legally once the "bonanzas"

faded away. With no credit, no roads, and no integration into national

markets, agricultural products cost too much to produce, and none

yielded any profit. That is still the case today. "The corn we

grow on a hectare (2.5 acres) costs 300,000 pesos (about US$150) to

produce and get to market," a peasant leader told us. "We

can’t sell it for that much."

A new

"bonanza" began when enterprising narcotraffickers, taking

advantage of the late-1970s U.S. appetite for cocaine, encouraged

some local farmers to grow coca. The illegal crop caught on quickly.

It grows like a weed in the otherwise poor soils of lower Putumayo,

allowing farmers to harvest its leaves four or five times per year.

Through a process involving gasoline, cement, and a few other chemicals,

producers create a white "paste" from the leaves in their

"laboratories" – really just sheds with a concrete

floor and a few 55-gallon drums. Leaves harvested from a hectare of

coca plants yield roughly two kilograms (4.4 pounds) of paste. This

compact load is easy to transport in an area whose few roads are difficult

enough for four-wheel-drive vehicles, much less cargo trucks, to negotiate.

"For any peasant, a backpack full of coca paste is better than

a truckload of potatoes," a local leader explained. Plus, a market

for the coca paste is guaranteed. Comisionistas, or middlemen,

pay a decent price in cash – about 2 million pesos (US$1,000)

per kilogram – an amount that rises after government eradication

efforts temporarily reduce supply.

While

no business or crop approaches coca’s profitability in Putumayo,

the farmer who grows it is the poorest link in a very long chain.

The kilogram of coca paste that nets farmers $1,000 will eventually

be turned into cocaine sold for over $100,000 on the streets of the

United States or Europe. But the farmer’s $1,000 is not even

pure profit. From that must be taken the cost of seeds, fertilizers

and pesticides, processing, and "taxes" charged by the FARC

guerrillas or right-wing paramilitaries (who often buy the coca paste

directly at artificially low prices). What is left for a farmer with

one or two hectares of coca is little more than Colombia’s legal

minimum wage of 286,000 pesos (about US$140) per month.

This

fits the living conditions of the coca-growing peasants we visited

in Putumayo. Families with one or two hectares generally lived in

one-room tin-roof wooden sheds – they could hardly be called

houses – without plumbing, electricity or nearby transportation.

Those with four or five hectares (an amount that, local authorities

told us, very few exceeded) appeared to be approaching middle class.

They had small houses made of painted cinder blocks, with a motor

scooter (one sees few cars on Putumayo’s roads), perhaps a TV

and VCR, and a refrigerator.

|

Putumayo: the latest

stop for South America’s wandering coca trade

Though

Putumayo has known coca since 1979, it was not a significant coca-growing

location until very recently. In fact, until the mid-1990s Colombia

itself was a distant third, behind Peru and Bolivia, among the

world’s main coca producers.

Colombia’s

Medellín and Cali drug cartels did not encourage much coca growing

on Colombian soil. Their networks bought coca grown in Peru and

Bolivia, then processed the coca base in Colombia and smuggled

out the finished product. This system had broken down by the mid-nineties,

though. The cartels had been smashed, the United States and Peru

were disrupting the aerial routes between growing areas and Colombian

processing sites, and some alternative development programs were

successfully weaning Peruvian and Bolivian peasants off of illegal

crops.

Colombia’s

narcotraffickers, now split among a multitude of smaller micro-cartels,

did not give up. They started buying Colombian-grown coca, spurring

a rapid expansion in Colombian coca cultivation that began around

1994-1995. But Putumayo, while a significant source, did not become

Colombia’s cocaine capital until a few years after that.

Colombia’s

mid-1990s center of coca production was in the departments of

Guaviare and Caquetá to the north of Putumayo, several hundred

miles closer to Bogotá (see map on facing page). In 1996, these

two departments combined for 60,400 of Colombia’s 69,200

hectares of coca, with only 7,000 planted in Putumayo.

Since

late 1995 the U.S. government and the Colombian National Police

have run a fumigation program in Guaviare and Caquetá, with aircraft

on regular spray missions raining the chemical glyphosate (the

active ingredient in the herbicide "Round-up") on the

coca fields. These fumigations went on for years without any U.S.

assistance for the affected peasants, such as efforts to ease

a transition to legal crops. The logical and foreseeable result

was that coca growers simply relocated out of the spray planes’

range – and new coca fields sprung up all over Putumayo in

the late 1990s.

By

2000, Colombia’s government estimated, over 55,000 hectares

in Putumayo were planted with coca – an eightfold growth

in four years. (In January 2001 the U.S. embassy said that this

figure "could be as high as 90,000 hectares.")

|

|

|

The mayor

of Puerto Asís, Putumayo’s largest city, Manuel Alzate is an

able politician whose skill with sound bites would take him far in

Washington. Mayor Alzate heaped scorn on the myth that Putumayo’s

peasants are getting wealthy from the coca trade. "If that were

true you would have seen at least some improvement after twenty years

of growing coca here. But the peasants’ houses look as miserable

as they did twenty years ago – son igualitas." Indeed,

Colombia’s planning ministry has found that 77 percent of Putumayo’s

households cannot meet their basic needs.

|

|

A

coca field in the Guamués valley. We took this photo

from the road.

|

Putumayo

is now overrun with coca, and nowhere more heavily than in the Guamués

River valley in the department’s southwest corner. On the road

from Puerto Asís to La Hormiga, the valley’s largest town, the

coca fields are hidden from view until southern Orito municipality

(county), when they become visible from the road. In what had been

dense jungle, neat rows of bright green bushes now grow amid the fallen

trunks of old-growth trees. Further south in the Guamués valley, the

coca bushes grow right up to the edge of the road.

About

90 percent of the farmers in this zone grow coca. Though the crop

is officially illegal, it is now part of the local culture. Coca has

given them, along with an army of young migrant leaf-pickers, or raspachines,

a guaranteed income in a country where official unemployment exceeds

20 percent. Middlemen and traffickers further up the production chain

have grown far wealthier. But many leaders complained to us that with

the easy money has come a "degenerate culture." Coca has

brought a weak work ethic, and none see education as necessary for

social mobility.

Violence

is at the core of this culture, and signs of it are everywhere in

Putumayo today. "Life in Putumayo is not worth 1,500 pesos (75

U.S. cents)," a peasant association leader told us. (Mayor Alzate

said the same thing, except 100 pesos.) In La Hormiga, we were told

that bodies by the roadside are a common early-morning sight. The

road into town is lined with bars where the region’s coca-pickers

come to drink, with curtains instead of doors and teenage prostitutes

called sardinitas loitering outside. Occasionally a patrol

from the nearby army battalion – three or four scared-looking

eighteen-year-olds carrying automatic weapons and rocket-propelled

grenades – walks down the main streets. A sign at the front desk

of our hotel read, "For your safety and ours, we pull down the

front gate at 11:00 PM. No exceptions." We spent a tense Saturday

night behind that gate, sleeping lightly amid the din of competing

vallenato tunes from La Hormiga’s many bars, the roar

of motorcycles, and occasional gunfire.

The

guerrillas

|

|

A

recently blown-up pipeline.

|

On the road

outside Villagarzón, we stopped at a roadblock that the local army battalion

had set up just outside its base (and only two or three miles beyond

the roadblock that the counternarcotics police had set up outside their

base). A friendly soldier looked through our bags, and asked where

we had come from. "La Hormiga," we told him; about a hundred

miles and five hours away. The soldier smiled and asked, "You didn’t

see any guerrillas, did you?"

We did

not see any of the FARC (Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces) guerrillas

on our trip, but while on the road we saw ample evidence of their

presence, and of the freedom of operation they obviously enjoy in

rural Putumayo. Our truck fishtailed through crude oil from guerrilla

bombings of the roadside pipeline leading out of Ecuador. Remnants

of pipeline bombings are a frequent roadside sight in Putumayo; we

passed through dozens of circular spots, usually about fifty feet

in diameter, in which everything – the road, the ground, plants

and trees – had been coated with a uniform black by the spilled

oil and flames. Puddles of crude formed by the roadside, or fouled

nearby ponds and streams. We drove through one spot that had been

bombed so recently that some of the oil on the ground was still smoking.

We saw

the burned remains of cars and buses that tried to defy the FARC’s

restrictions on road travel. We passed cargo trucks bearing slogans

(including "Plan Colombia = plan for war") that the guerrillas

spray-paint at roadblocks, warning the truck drivers against removing

them. Passing through a forested area, a fellow passenger asked our

driver, "this is the zone where they’ve been holding people

up, isn’t it?" "Yes, just about every day," he

replied. Nobody travels on Putumayo’s roads between 6 PM and

6 AM.

The FARC

established a permanent presence in Putumayo during the early 1980s.

It was not the first guerrilla group to operate in the area; the leftist

M-19 and Maoist EPL had been active in Putumayo during the late 1970s

and the beginning of the 1980s, but both had vacated the zone by the

time the FARC’s 32nd Front arrived. Another front, the 48th,

was created in Putumayo in the early 1990s, and several fronts from

neighboring departments also pass through frequently.

Until

very recently, the FARC were the undisputed masters of Putumayo, and

though they have lost town centers to the paramilitaries, the guerrillas

clearly continue to dominate rural areas. FARC fronts forcibly recruit

new members, including teenagers, in Putumayo’s villages. The

guerrillas force still others to undergo military training, then threaten

harm to their families if they leave the area.

|

|

Puerto

Asís.

|

The FARC

also has a close relationship to Putumayo’s coca trade. They

charge "taxes" on coca production, as they do with all economic

activity in the areas that they control. Local producers told us that

they have also begun to go further than mere taxation, buying the

coca paste themselves at fixed prices.

In 1996,

after the U.S.-supported fumigation program began in Guaviare and

Caquetá to the north, the FARC organized massive peasant protests

throughout southern Colombia, including Putumayo. Weeks of marches,

with some violence, ended when the Bogotá government agreed to carry

out infrastructure projects, crop substitution programs, and development

assistance. The government never came close to following through on

its commitments, though, and the 1996 marches are generally regarded

as a failure. The local peasants, who lost income because the protests

took them away from their land, directed their anger and mistrust

not just at Bogotá, but also at the FARC.

The marches,

the forced recruitments, and the increasing levies on the coca trade

have deeply eroded the FARC’s base of support. Some whom we interviewed

spoke in almost nostalgic terms about the guerrilla leaders who had

run Putumayo during the 1980s and early 1990s, describing them as

fair and understanding of the local peasants. But "coca changed

the FARC," they said. As the FARC’s Southern Bloc became

wealthier and militarily successful, its leaders in Putumayo –

including Joaquín Gómez, now a member of the top leadership –

occupied themselves less with their support base and more with the

coca trade’s contributions to their war chest.

The

paramilitaries

In many

of Putumayo’s towns one sees the very open presence of another

illegal armed group, the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC),

the country’s main right-wing paramilitary organization. In the

coca zones of lower Putumayo, entering a populated area – whether

a small city or a crossroads town – can feel almost like entering

another country. This is paramilitary territory, where dozens of the

men the locals call "power rangers" operate in plain sight,

usually dressed in civilian clothes.

La Dorada,

a town in the southern Guamués valley very close to the Ecuador border,

has a beautiful central park that the municipal government completed

in the middle of 2000, after much persuading of the FARC guerrillas

who then dominated the town. The park was almost completely empty

when we visited La Dorada – no children on the brightly painted

jungle gym, nobody walking on the manicured lawn, and nobody sitting

on the new benches. In fact, the whole town center was empty, except

for groups of young men, many of them obviously well armed.

|

|

Driving

down Putumayo’s bumpy main road.

|

The paramilitaries

forced the FARC out of La Dorada with a massive incursion that started

on September 21, 2000. It did not take them long to install themselves

permanently. As elsewhere, they did it not by defeating the FARC militarily

– though firefights in the middle of town were a near-daily occurrence

for months – but by killing and displacing civilians they considered

to be guerrilla collaborators. Paramilitary fighters also carried

out what they call "cleansing" of suspect civilians in the

rural villages surrounding La Dorada. While the full extent of their

rampage is unknown, by early October more than 800 displaced people

from the surrounding countryside had arrived in La Dorada. Many more

went elsewhere, including Ecuador.

After

speaking with local officials, including the government human rights

ombudsman (who has been unable to leave this small town since last

August), we hurried out of La Dorada before the guerrilla restrictions

on road travel began. By the roadside at the entrance to the town

were two armed paramilitary guards in civilian clothes, one talking

into a field radio. About half a mile further, perhaps fifteen minutes

from the La Hormiga army base, we came upon a column of about ten

men in camouflage fatigues with "AUC" stenciled in white

letters on the back, carrying Galil rifles and walking down the middle

of the main road. We proceeded slowly and they let us pass, staring

at us. While we didn’t stare back, we couldn’t help noticing

that most of them appeared well over thirty years old, quite different

from the young conscripts the army sends on patrol or the child soldiers

the guerrillas recruit. Perhaps they had prior experience in other

military organizations.

While

La Dorada is one of the AUC’s latest conquests, the paramilitaries

themselves are recent arrivals in Putumayo. The group, founded in

northern Colombia and funded by landowners and narcotraffickers, was

unheard of in Putumayo until after the 1996 anti-fumigation protests,

when their leader, Carlos Castaño, announced the formation of a bloc

of "southern self-defense groups." They swept into the region

in late 1997 and early 1998 with a series of horrific massacres and

selective killings. Since then they have moved quickly. By 1999 paramilitaries

had gained control of Puerto Asís, and by early 2000 they controlled

La Hormiga, Orito, and the roadside village of El Placer, where they

maintain a base of operations. They took La Dorada in September 2000

and in December, in an operation that local leaders say has since

killed 120 people, they established themselves in Puerto Caicedo.

A few

towns in the southwestern Putumayo coca zone still remain under FARC

control. One is El Tigre, along the main road in Orito municipality.

While the AUC does not control El Tigre, its residents remember when

they first appeared on January 9, 1999, a few days after the government

began peace talks with the FARC. A column of 150 paramilitaries swept

through, killing twenty-six people in the main square and disappearing

fourteen more. Locals told us that after the massacre, the first vehicles

allowed to proceed into town had to swerve to avoid hitting dead bodies

in the road. Others told of people being hacked to death with machetes

and thrown into the nearby river. The paramilitaries may be back again

soon. Driving through the town, we saw a chilling message in fresh

graffiti painted on a house: "AUC – we’re here to stay.

El Tigre will be erased from the map."

While

they mainly dominate town centers, the paramilitaries are active in

rural areas around the towns they control, killing hundreds and displacing

thousands. They maintain roadblocks and tightly control access to

and from the towns. Indigenous leaders told us that it is unsafe for

them to travel alone on the rivers because the AUC stops them and

questions them about their business. The paramilitaries also "tax"

coca production, and many analysts speculate that their offensive

in Putumayo has more to do with increasing their coca income than

with carrying out an anti-guerrilla crusade.

|

|

The

Putumayo River.

|

On condition

of anonymity, many whom we interviewed insisted that the paramilitaries’

success in Putumayo was made possible by the local military forces’

collaboration and toleration. Paramilitaries operate openly and unmolested

in Putumayo – as we saw for ourselves – and combat between

the Army and the AUC is exceedingly rare. Some sources told us of

joint actions, and of paramilitaries being present at military bases.

A reporter played us a tape of a recent interview with the head of

the 24th

Brigade (based in the capital, Mocoa) in which the colonel acknowledged

that the Brigade’s 59th

Battalion was replacing the 31st

Battalion at the La Hormiga base because the latter faced widespread

allegations of collaboration with the AUC.

In October

2000, a bold police officer denounced military-paramilitary cooperation

in Puerto Asís to local civilian authorities. According to the Bogotá

daily El Tiempo, the policeman reported that the paramilitaries

blatantly identify themselves with insignia and move easily in clearly

marked vehicles. The policeman said he did not understand "the

abilities and skills that they use to make a mockery of the Army’s

roadblocks, and to station themselves right in front of them."

He added that he had heard numerous charges that the local army command

meets regularly with paramilitary leaders at a well-known compound

called Villa Sandra. The site, in the town of Santana just north of

Puerto Asís, is only a few hundred yards from an Army base currently

occupied by a brand-new U.S.-funded counternarcotics battalion. (We

did not see any people on the grounds of Villa Sandra on the two occasions

that we passed the site.)

In its

mid-March 2001 report, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human

Rights cites a permanent paramilitary roadblock in El Placer, the

continued existence of the Villa Sandra paramilitary base, including

its use as a site for military-paramilitary meetings, and the prolonged

AUC takeover of La Dorada despite the proximity of an army base in

nearby La Hormiga.

|

Excerpt

from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ 2000 report

(Published

February 8, 2001 and released in March 2001)

At

the entrance to the village of El Placer, a notorious paramilitary

roadblock exists just fifteen minutes from La Hormiga, where

an army battalion belonging to the 24th Brigade is based. Eight

months after the [High Commissioner’s] Office reported

observing this directly, the roadblock was still in operation.

The military authorities denied in writing that this paramilitary

position exists. The Office also observed that at the hacienda

"Villa Sandra," between Puerto Asís and Santana, the

paramilitaries are still operating only a few minutes from the

24th Brigade’s installations. Afterward we were informed

of two searches of the site carried out by the security forces,

which apparently found nothing. However, the existence and maintenance

of this paramilitary position is a matter of full public knowledge,

so much that it was visited several times by international journalists,

who published their interviews with the paramilitary commander

there. Testimonies received by the Office have even included

accounts of meetings between members of the security forces

and paramilitaries at "Villa Sandra." At the end of

July [2000], the Office alerted the authorities to an imminent

paramilitary incursion in the town center of La Dorada, in San

Miguel municipality [county], which indeed happened on September

21. The paramilitaries remain there, even though the town is

only a few minutes from the army base at La Hormiga.

|

Another

factor in the paramilitaries’ takeover was the local population’s

growing disenchantment with the guerrillas. While this goes back to

the failed 1996 peasant marches, the FARC has made things worse for

itself with its heavy-handed response to the paramilitary offensive.

The guerrillas have consistently chosen to retaliate in ways that

inflict more harm on the civilian population than on the paramilitaries,

such as killing unfamiliar people and setting off car bombs in town

centers.

After

the paramilitary takeover of La Dorada, the FARC shed even more goodwill

by mounting an "armed stoppage" aimed at isolating the paramilitaries

in the towns. For over eighty days starting in late September 2000,

the guerrillas banned all travel on Putumayo’s roads, setting

fire to any vehicles they found. (The roadsides remain littered with

oxidized heaps of twisted metal that vaguely resemble car and bus

chassis.) Townspeople were prisoners in their towns, while much of

the countryside was brought to the brink of famine.

Residents

of La Dorada told us of the trauma of living through the bloody paramilitary

takeover followed by the armed stoppage. After the FARC lifted the

vehicle ban in mid-December there was about a seven-day pause when

"people even felt safe to use the park." Then, on December

19, the fumigations began.

Fumigation

and the U.S. aid package

Between

December 19 and early February, a U.S.-funded Colombian military and

police operation sprayed glyphosate on 25,000 to 29,000 hectares (62,500

to 72,500 acres), nearly all of it in the Guamués River valley. It

was the first U.S.-supported spray operation ever in Putumayo, and

the first visible result of a two-year, $1.3 billion aid package for

Colombia and its neighbors that President Clinton signed into law

in July 2000.

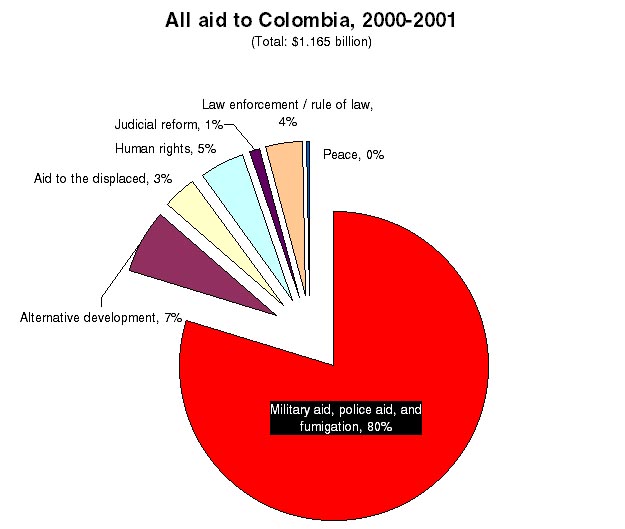

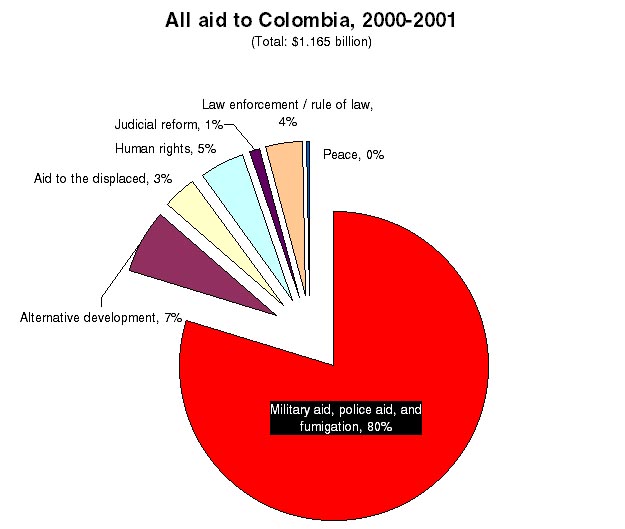

The aid

package was billed as a contribution to "Plan Colombia,"

a $7.5 billion Colombian government program aimed at fighting drugs

and strengthening Bogotá’s ability to govern. Colombian government

officials insist that their program is only 25 percent military and

police aid, with the other 75 percent going to social and economic

programs. With $860 million coming from last July’s aid package,

the United States is providing Colombia $1.165 billion during 2000

and 2001. Of this amount, $929 million – 80 percent – is

aid for Colombia’s military, police, and fumigation program,

most of it focused on Putumayo.

The centerpiece

of this program is "the push into southern Colombia" –

a military offensive designed to make fumigation possible in Putumayo.

U.S. policymakers decided against duplicating the fumigation model

used for years in Guaviare and Caquetá departments to the north, where

U.S. contractor pilots fly spray missions accompanied by police escort

helicopters. Because of the heavy presence of armed groups who shoot

back at the spray planes, fumigating Putumayo was considered too dangerous

without a large military effort. As a result, last year’s aid

package included funds to create three new battalions in the Colombian

Army, which are to receive dozens of Blackhawk and upgraded Huey helicopters.

The battalions’

mission is to make Putumayo safe for fumigation by fighting off any

armed groups in the zones to be sprayed. As former U.S. Southern Command

chief Gen. Charles Wilhelm told a Senate committee, with the 2,300

men in the three battalions "Colombia can achieve a ‘one-two

punch’ with the armed forces preceding the police into narcotics

cultivation and production areas and setting the security conditions

that are mandatory for safe and productive execution of eradication

and other counterdrug operations by the CNP [Colombian National Police]."

Critics worry that "setting the security conditions" may

require U.S.-aided units to engage in regular combat with insurgent

and paramilitary groups, bringing Washington closer than ever before

to Colombia’s civil war.

The military

money is being spent in a hurry. Two of the three battalions are ready

for action, and the third will complete training in May 2001. Though

the State Department originally scheduled to deliver the first helicopters

in October 2002, congressional hard-liners’ bitter complaints

moved the delivery date up to July 2001. In December 2000, with two

battalions ready and thirty "temporary" 1970s-vintage helicopters

delivered, the United States gave the green light to fumigation in

Putumayo.

With

the battalions and the police operating on the ground, a fleet of

Turbo Thrush spray aircraft accompanied by Colombian Police and Army

helicopters flew daily missions over the Guamués valley. They sprayed

"Round-Up Ultra," a combination of glyphosate and two additives

(known as Cosmo Flux-411f and Cosmo-iN-D) that help the poison stick

to the coca leaves and keep the spray nozzles from getting clogged.

U.S.

government officials are telling Congress and the media that this

first phase of spraying was a huge success. "Overall, operations

in southern Colombia have gone much better than expected with only

minimal local opposition, few logistical problems, and no major increase

in displaced persons," Assistant Secretary of State for International

Narcotics Affairs Rand Beers told a congressional subcommittee in

late February.

|

|

Fumigated

coca bushes outside La Hormiga.

|

The spray

planes and battalions encountered surprisingly little resistance.

In the first seven weeks of the eight-week effort, eight spray planes

and escort helicopters were hit by ground fire, with no injuries or

serious damage. This is far safer than Guaviare and Caquetá, where

in 2000 the planes were hit fifty-six times while spraying 47,000

hectares – four times as often per hectare sprayed. Colombian

forces "setting the security conditions" were involved in

only five minor combat incidents, three with the FARC, one with the

paramilitaries, and one with an unknown assailant who fired a rocket-propelled

grenade at a fuel plane (some speculated that it was a firework).

The spray operation took place in conditions so safe that eradication

could almost have been performed manually.

We asked

a wide range of people why the fumigation met so little resistance.

Some argued that the Colombian Army, including the new battalions,

did indeed manage to create the necessary security conditions. Gonzalo

de Francisco, the Colombian government official in charge of anti-drug

activities in Putumayo, said that the lack of resistance owed to good

coordination between the army and the police and the local population’s

confidence in upcoming crop-substitution programs.

This

rationale does not explain, however, how the fumigations proceeded

in a FARC stronghold with so few combat incidents. The answer to that

lies in the State Department’s explanation that "the original

spray area was an area dominated, for the most part, by the AUC paramilitary

institution."

This

is true, though the fumigation zones became "paramilitary dominated"

only very shortly before the spray planes arrived. Much of the area

where fumigation occurred between December 2000 and February 2001

– La Dorada, La Hormiga and surrounding San Miguel and Valle

del Guamués municipalities – was subject to a paramilitary campaign

of murders and forced displacement that greatly reduced the presence

of guerrillas in the months leading up to the spraying. With the FARC

cleared out, the paramilitaries who took over allowed the fumigation

program to operate unhindered. A paramilitary leader in Putumayo named

"Enrique" told the Miami Herald’s Juan Tamayo in January

that "his men are under orders not to shoot at the planes, saying

in an interview that while he ‘taxes’ area coca dealers

to finance AUC operations, ‘we are 100 percent in favor of eradication.’"

Some

people we spoke with in Putumayo wondered whether any connection exists

between the late 2000 paramilitary offensive and the December 2000

onset of fumigation. Though we found overwhelming evidence of military-paramilitary

collaboration in the area, we found no evidence of a conscious strategy

to employ paramilitaries specifically to ease the first phase of fumigations.

We are

nonetheless convinced that U.S.-aided Colombian units do not get all

the credit for the lack of resistance to the spray aircraft. The fumigations

between December 2000 and February 2001 were eased – security

conditions were established – by the paramilitaries’ often

brutal activities in the fumigation zone in the months preceding the

spraying.

The

"industrial" coca-growing zone

As we

drove into the Guamués valley, the lush green of Putumayo rather suddenly

gave way to yellow and brown. We had entered the zone the spray planes

had flown over several weeks earlier. The herbicides clearly did their

job; walking through the coca fields, it was even possible to tell

which way the wind was blowing when the planes came. But they killed

everything else, too. The barren landscape was punctuated with dead

underbrush and severely damaged old-growth trees. In a field of plantains

rotting on dried-out trees, we watched a troop of monkeys foraging

for food.

U.S.

officials had told Congress and the public since mid-2000 that the

Guamués valley would be the target area for the first fumigations.

They characterized the area as a zone of "industrial" coca-growing,

with large plantations run by distant drug lords. The vast majority

of the population, they said, was a "floating population"

of young male migrant workers and raspachines.

On March

12, 2001, while we were still in Putumayo, Deputy Assistant Secretary

of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Bill Brownfield explained

this position to reporters at a briefing in Washington. "For

the most part, most of those who were sprayed, most of the land that

was sprayed in the December/January/February time-frame in Putumayo

… were, by our estimation, what we call industrial-sized coca

plantations or coca-cultivated areas. Industrial size, meaning too

large to be managed by a single campesino [peasant] or campesino

family as part of a long-term, multi-generational presence on

a specific piece of land. These were fairly large in size."

Though

it is still bustling, locals told us that La Hormiga is a ghost town

compared to a few months ago, before the spraying started. It is certain

that, as the U.S. aid program foresaw, much of the zone’s "floating

population" did indeed float away. But they left behind thousands

of peasant families, small landholders whom the fumigations have left

with no way to support themselves.

|

|

Children

in the town of La Isla in the “industrial” coca-growing

zone.

|

In aerial

surveillance and satellite photos, many of the Guamués valley’s

coca fields may resemble "industrial" plantations. The reality

on the ground is quite different. We walked through coca fields that

seemed to stretch as far as the eye could see, but from the ground

it was obvious that these were small parcels of individually owned

land adjoining each other. Several people told us that individual

plots rarely exceed four hectares, with the largest few reaching seven

or eight. San Miguel municipality, in the heart of the zone, has 18,000

hectares of coca divided among a rural population of 20,000.

Because

of the belief that this is an "industrial" zone, the U.S.

government has allocated nothing for humanitarian aid or alternative

development assistance in the area sprayed in December, January and

February. The many families in the zone, who have lost both their

coca and their food crops, fall outside the focus of the meager economic

component of the U.S.-funded program in Putumayo. Though officials

in Bogotá say that some aid has been delivered with Colombian government

funds, we spoke with nobody who had received any.

We stopped

in the roadside town of La Concordia, north of La Hormiga, where the

planes sprayed everything – food crops, people’s houses,

the school, the soccer field, the road itself. A farmer named Rigoberto

showed us his destroyed fields. There was no doubt that he had planted

his food crops alongside his coca. The fumigation planes did not violate

procedure when they destroyed all of his crops, legal and illegal.

The result, however, is that he and his family are left with nothing

to eat.

|

|

Destroyed

alternative development projects in La Isla: a chicken coop

(above) and a fish pond (below).

|

|

We asked

Rigoberto what he and his neighbors are doing – were they planting

food, how were they feeding themselves. He said that many in La Concordia

were now "aguantando hambre" – suffering from

hunger. Since everybody expected the fumigation planes to come back

soon, they were not planting anything, legal or illegal. "We

spend the day here with our arms crossed, wondering what to do."

Even though La Concordia is on the main road – no need to hike

into the backcountry – no humanitarian aid had reached its residents.

The State

Department’s Brownfield explained that no aid will be forthcoming

for families like Rigoberto’s who planted both coca and food

crops on the same plot of land in the "industrial" zone.

"The campesino who is intentionally hiding, concealing

or trying to protect illicit cultivation of coca or opium poppy isn’t

going to get a tremendous amount of support or concern or commiseration

if he is sprayed," he told the March 12 briefing.

La Isla,

a village not far from La Concordia, was one of the first towns to

be fumigated. The locals said the planes came on December 22. The

planes passed over the town itself, misting Round-up Ultra through

their shacks’ glassless windows. The herbicides killed all of

the residents’ food crops, and destroyed two nearby development

projects designed to create legal economic alternatives. One was a

former coca-paste lab that had been turned into a chicken coop with

funding from PLANTE, the Colombian government alternative development

agency. The other was an aquaculture project. Both the chicken coop

and the man-made pond were empty; La Isla residents told us that the

chickens and the fish were dead within a few days of the spraying.

|

|

These

coca plants, cut back just after fumigation, are quickly growing

back.

|

Though

glyphosate is a water-soluble herbicide that is supposed to break

down within a few days, farmers in La Isla told us that they still

cannot get anything to grow. "The seeds germinate, grow for a

few days, then die," one resident said. In fact, the only crop

that seems to be doing well is the coca itself. Local growers have

found that when they cut the coca bush back to its main stem before

or shortly after the spraying, it grows back rapidly and yields more

leaves than before. We walked through several fields where bright-green

knee-high coca plants grew among dead banana trees and brown underbrush.

U.S.

officials have categorically denied that the fumigations could be

the cause of any health problems among the affected population. In

a meeting with the head of the U.S. embassy’s narcotics section,

Mayor Alzate was told that glyphosate is so safe that one could drink

a water glass full of it. (The official declined Alzate’s request

that he do so.)

|

|

This

baby’s mother said her skin condition appeared just after

the spray planes hit La Isla in December.

|

Yet we

both saw and heard evidence that the spraying had sharply increased

cases of skin outbreaks, gastrointestinal disorders like vomiting

and diarrhea, and respiratory ailments. A physician in La Hormiga

told us that young children were the most heavily affected, and that

the effects appeared to be stronger at the outset of the fumigations

in late December. He speculated that perhaps the additives in the

spray mix were to blame. Most people no longer showed symptoms when

we arrived many weeks later; most remaining skin disorders had faded

to a few patches. In La Isla, however, we saw a five-month-old baby

whose skin was covered with bumps, scabs and rashes. Her mother said

that the condition appeared immediately after the spray planes flew

over the town in late December, and that because she scratches herself,

the inflammation has only grown worse.

Putumayo’s

indigenous communities, especially the Cofán people of the Guamués

valley, have also been hit hard by the fumigations. Indigenous leaders

told us that while they plant little coca themselves, their reservations

have been invaded by illegal squatters (colonos) who grow significant

amounts, attracting the fumigation planes. The spraying destroyed

both indigenous communities’ food crops and their sacred ceremonial

crops, such as yagé.

|

|

Dead

banana trees indicate that the spray planes passed directly

over this shack.

|

Without

humanitarian and alternative development assistance, the families

we did not expect to find in the "industrial zone" may soon

be facing famine. Or they may choose to relocate elsewhere into Colombia’s

California-sized jungles, knock down a few more hectares of trees,

and plant more coca.

A January

28 U.S. Embassy document claims that "there has been minimal

displacement, with some 20-30 people displaced since spray operations

began in mid-December." Everyone in Putumayo to whom we read

this statistic reacted with disbelief. Since the fumigations began,

leaders in La Dorada told us, peasants have been leaving the area

by the truckload – about four or five loads per day.

Many

of those displaced are planting new coca elsewhere in Colombia. A

common destination is Nariño department to the west, where coca cultivation

is now increasing rapidly. Others are moving to Puerto Leguízamo municipality

in southeastern Putumayo, to Colombia’s large, empty department

of Amazonas, and across the border into Ecuador. By many accounts,

the fumigations of December through February brought a 25 percent

increase in the price of coca paste, making coca-growing that much

more attractive. "When they fumigate forty hectares, eighty more

appear," Puerto Asís Mayor Alzate told us.

The

social pacts

U.S.

and Colombian officials are quick to emphasize that their plans in

Putumayo go beyond military offensives and aerial fumigation. They

point out that they have made funding available for a series of "social

pacts" with local producers who are willing to give up coca voluntarily.

Peasants

who sign the pacts agree to eradicate their coca manually within twelve

months in exchange for funding, credit, and technical assistance for

the cultivation of legal crops. The agreements, signed with hundreds

of farmers in a single community, are managed by the Colombian government

alternative development agency (PLANTE) and carried out by a non-governmental

organization (NGO) working on a contract basis. Each contracted NGO

will manage five pacts. The farmers who sign the pacts will receive

in-kind assistance valued at 2 million pesos (about US$1,000), and

will have access to credit and technical assistance (one technician

will be assigned to each 100 farmers). Infrastructure projects, such

as road building, are also foreseen. Farmers who do not eradicate

their crops within twelve months of receiving funds will face fumigation. Peasants

who sign the pacts agree to eradicate their coca manually within twelve

months in exchange for funding, credit, and technical assistance for

the cultivation of legal crops. The agreements, signed with hundreds

of farmers in a single community, are managed by the Colombian government

alternative development agency (PLANTE) and carried out by a non-governmental

organization (NGO) working on a contract basis. Each contracted NGO

will manage five pacts. The farmers who sign the pacts will receive

in-kind assistance valued at 2 million pesos (about US$1,000), and

will have access to credit and technical assistance (one technician

will be assigned to each 100 farmers). Infrastructure projects, such

as road building, are also foreseen. Farmers who do not eradicate

their crops within twelve months of receiving funds will face fumigation.

So far,

the Colombian government has signed four pacts. The U.S. government’s

aid package has sponsored two of these: a December 2, 2000 pact in

Puerto Asís and a January 15 pact in Santana, a town in Puerto Asís

municipality. These two agreements incorporate 1,453 families. Two

others have been signed with Colombian funds: a February accord with

an indigenous community in San Miguel municipality, and a March 15

pact in Orito. The U.S.-supported pacts are outside the so-called

"industrial zone," which will get no U.S. economic aid at

all.

The region’s

coca-growing peasants, most of whom would welcome an opportunity to

abandon coca, are watching the pacts very closely. Their mistrust

of government alternative development programs dates back at least

to Bogotá’s noncompliance with the agreements that ended the

1996 anti-fumigation protests. It has been compounded by other colossal

failures, like a half-built wreck of a hearts-of-palm processing plant

that sits outside Puerto Asís, a monument to a PLANTE project that

never got off the ground.

The U.S.

embassy reported in late January, "The signing of even two elimination

agreements has had a positive effect, in that many more families are

interested in signing them now that they are perceived as a reality.

The signings appear to have lessened some local officials’ opposition

to aerial eradication as well."

When

we came to Putumayo in mid-March, we found that not a cent had arrived

for those who had signed the pacts months earlier. Instead of an active

alternative development project, all we found were angry and discouraged

peasants. Because of a lengthy negotiation process with Fundaempresa,

the Cali-based NGO chosen to administer the first pacts, no aid had

been disbursed and nobody had contacted the signatories in Puerto

Asís and Santana to let them know what was happening. When

we came to Putumayo in mid-March, we found that not a cent had arrived

for those who had signed the pacts months earlier. Instead of an active

alternative development project, all we found were angry and discouraged

peasants. Because of a lengthy negotiation process with Fundaempresa,

the Cali-based NGO chosen to administer the first pacts, no aid had

been disbursed and nobody had contacted the signatories in Puerto

Asís and Santana to let them know what was happening.

Doubts

and uncertainty grew after an incident that was brought to our attention

several times during our trip. According to local leaders and the

affected farmers, in early February a contingent of troops from the

new U.S.-created counternarcotics battalions paid visits to thirteen

families in the villages of La Esperanza, La Planada, Bretania, Yarinal

and Santa Elena, in the municipality of Puerto Asís. The thirteen

families had signed the first social pact in December, and were awaiting

funds.

Gustavo

(name changed for security reasons), one of the farmers whom the battalion

visited, is one of the better-off coca-growers we met. He welcomed

us into his three-room house, with glass windows, a fan, a television,

stereo, and a shelf full of books. He told us that the soldiers from

the battalion came one morning, chatted with him and his wife, then

asked him to sign a paper certifying that he had been treated well.

Once he signed, the troops marched into his coca fields, pulled up

plants and burned his coca-paste laboratory.

Gustavo

protested that, as a signer of a social pact, he had twelve months

to eradicate his coca. He told us that the soldiers replied, "How

stupid and foolish you peasants are. You believe the politicians who

say they are going to help you. We don’t know of any Señor de

Francisco [Gonzalo de Francisco is the Colombian government official

in charge of anti-drug efforts in Putumayo]. The United States pays

us directly."

Whether

true or not, news of this incident has spread throughout Putumayo,

weakening peasants’ will to enter into future pacts. (Gonzalo

de Francisco told us that if the incident did occur, which he doubted,

it was an error.) While de Francisco told us on March 13 that disbursements

of funds for the first pacts should begin in four weeks, in Putumayo

there is a growing sense that the peasants are being fooled yet again.

"It’s all pure bureaucracy, they’re going to waste

it all on per diems," a peasant leader told us. "It will

be like the hearts-of-palm plant all over again." On a few occasions,

we found ourselves in the odd position of defending the U.S. government

before angry farmers, assuring them that this time the aid had to

arrive because it was included in U.S. law. Whether

true or not, news of this incident has spread throughout Putumayo,

weakening peasants’ will to enter into future pacts. (Gonzalo

de Francisco told us that if the incident did occur, which he doubted,

it was an error.) While de Francisco told us on March 13 that disbursements

of funds for the first pacts should begin in four weeks, in Putumayo

there is a growing sense that the peasants are being fooled yet again.

"It’s all pure bureaucracy, they’re going to waste

it all on per diems," a peasant leader told us. "It will

be like the hearts-of-palm plant all over again." On a few occasions,

we found ourselves in the odd position of defending the U.S. government

before angry farmers, assuring them that this time the aid had to

arrive because it was included in U.S. law.

It is

crucial that the funds for the pacts reach their destination with

no further delay. All eyes in Putumayo are on these initial projects,

and if they prove to be successful they could have an enormous demonstration

effect. Trust in the Colombian government could be established for

the first time, laying the groundwork for future coca-eradication

projects that do not depend on fumigation.

So far,

however, the residents of Putumayo have seen a rush to deliver helicopters,

train battalions and spray farmers, and a halfhearted attempt to carry

out economic alternatives. As of this writing, the U.S. approach to

Putumayo – whose supporters sell it as a "balanced approach"

– has been 100 percent military.

A better

approach

Everyone

we talked to in Putumayo – from mayors and council members to

farmers by the roadside – was adamantly opposed to fumigation.

While we were in Putumayo, the department’s governor was in Washington

spreading the same message. "Fumigation is not the solution,"

Iván Gerardo Guerrero told a press conference on March 12. "It

has a great defect. It doesn’t really take into account the human

being. All it cares about are satellite pictures."

We heard

uniform opposition to increased military aid as well. Those who live

in Putumayo’s day-to-day reality see the region’s problem

as social, and view a military response as absurd. "Instead of

sixty helicopters, the United States should be sending us sixty road-graders

or tractors," Mayor Alzate told us. The mayor scoffed at the

notion, heard often in Washington, that drug eradication in Putumayo

could weaken the FARC guerrillas by taking away their income. "The

guerrillas will be just as strong without coca. They can increase

kidnapping and extortion to support themselves. They’re powerful

in many parts of the country that don’t have any coca."

Putumayo

residents generally agreed that an effective coca-eradication strategy

must be manual, gradual, and mutually agreed with the affected communities.

The social pact structure includes these elements to some extent,

but ultimately fails on all three.

While

the pacts include manual eradication, they carry the threat of aerial

fumigation if coca plants are not pulled out in the agreed period.

The pacts allow producers to taper off coca-growing gradually over

twelve months, but most insist that the transition should be longer.

While coca can yield a first harvest within a few months, most other

crops will take longer, often well over a year, to bring in any income.

Most crops that thrive in the generally poor soils of lower Putumayo,

such as rubber, bananas, or hearts-of-palm, grow on trees that will

still be saplings after a year. Since 1999 the Municipal Rural Development

Commission of Puerto Asís, a prominent peasant group, has been promoting

a crop-substitution plan with a three-year tapering-off period. The

social pacts may risk failure unless the government either allows

signers to taper off coca-growing more gradually, or pays them a basic

wage while they await their first legal harvests. While

the pacts include manual eradication, they carry the threat of aerial

fumigation if coca plants are not pulled out in the agreed period.

The pacts allow producers to taper off coca-growing gradually over

twelve months, but most insist that the transition should be longer.

While coca can yield a first harvest within a few months, most other

crops will take longer, often well over a year, to bring in any income.

Most crops that thrive in the generally poor soils of lower Putumayo,

such as rubber, bananas, or hearts-of-palm, grow on trees that will

still be saplings after a year. Since 1999 the Municipal Rural Development

Commission of Puerto Asís, a prominent peasant group, has been promoting

a crop-substitution plan with a three-year tapering-off period. The

social pacts may risk failure unless the government either allows

signers to taper off coca-growing more gradually, or pays them a basic

wage while they await their first legal harvests.

Though

they take the form of a mutual agreement, the terms of the pacts are

handed down by the government in a "take it or leave it"

fashion. Local producers complain that Bogotá government officials

are imposing the pacts without ever consulting with the affected communities.

An indigenous leader suggested that Gonzalo de Francisco "come

to Putumayo more often and hold public discussions and forums with

the affected population, instead of just meeting with the mayors and

town council members." Leaders of agricultural and indigenous

organizations wondered why the government felt it necessary to contract

with organizations from outside the region, such as Fundaempresa,

to administer the aid and to design alternative development projects.

Some expressed alarm that many of the pacts may encourage farmers

to cultivate African palm (a source of palm oil), a non-native plant

that produces little employment per hectare.

Alternative

development, many pointed out, is more than just crop substitution.

The department is in desperate need of basic infrastructure, from

potable water to farm-to-market roads. Agricultural producers demand

assistance with marketing their produce, access to credit, and –

at least in the short term – a guaranteed price for their legal

crops. Education is another deeply unmet need; as much as 85 percent

of Putumayo’s population has never been in school beyond the

fourth grade.

These

initiatives would have a greater chance of success if the United States

would do more to reduce demand for drugs at home, especially by expanding

treatment programs for the hard-core addicts who account for most

domestic drug use. (While treatment funding did rise 41 percent since

1994, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy notes,

funding for foreign anti-drug aid, most of it military, increased

by 175 percent.) Peasants in Colombia do not deserve a military approach.

Military and police efforts should be aimed higher up the drug-production

chain, against the drug kingpins, the importers of precursor chemicals,

and the financial entities that help the narcotraffickers launder

their money.

Washington

and Bogotá are likely to ignore the local population’s proposals

for a manual, gradual, and mutually agreed program and go ahead with

the spraying and battalions. This may indeed bring a sharp reduction

in the amount of coca grown in Putumayo. But the coca trade will continue

to flourish, powered by an endless army of unemployed and uneducated

migrants who will find a way to feed themselves elsewhere.

The U.S.

anti-drug strategy now underway in Putumayo – rapidly expanding

fumigation and seriously lagging development assistance – has

already been tried elsewhere in Colombia. So far, it has done little

more than inconvenience the coca trade, forcing it to relocate somewhere

else every few years while total acreage continues to increase. It

is this approach that caused Putumayo to be overrun with coca in the

late 1990s. The same response in Putumayo will succeed only in moving

coca growing to another patch of untouched jungle, either in Colombia

or across the border in Ecuador, Peru or Brazil.

The relocated

coca will bring environmental destruction, armed groups, random violence,

and further fumigation plans to places that still look the way Putumayo

did twenty years ago. "Look how we’ve destroyed our own

house," one longtime Putumayo resident said to us, lamenting

his region’s lost forests, beauty, and tranquility. If the United

States and Colombian governments change course in time, perhaps others’

houses can yet remain unspoiled.

The Center

for International Policy wishes to thank the CarEth Foundation, the

Compton Foundation, the General Service Foundation, the Stuart Mott

Charitable Trust, and the Academy for Educational Development for the

financial support that made our visit possible. We also send our deepest

expressions of gratitude to those who served as our guides and advisors

during our stay in Putumayo.

|

|

|

CIP

Senior Associate Adam Isacson (left) and Associate Ingrid Vaicius

(right) in Putumayo.

|

Center

for International Policy

1755 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Suite 312

Washington, DC 20036

(202) 232-3317

Fax: (202) 232-3440

cip@ciponline.org

www.ciponline.org

A Publication of the Center for International Policy

©

Copyright 2001 by the Center for International Policy. All rights reserved.

Any material herein may be quoted without permission, with credit to

the Center for International Policy. The Center is a nonprofit educational

and research organization promoting a U.S. foreign policy based on international

cooperation, demilitarization and respect for basic human rights.

ISSN 0738-6508

|

Peasants

who sign the pacts agree to eradicate their coca manually within twelve

months in exchange for funding, credit, and technical assistance for

the cultivation of legal crops. The agreements, signed with hundreds

of farmers in a single community, are managed by the Colombian government

alternative development agency (PLANTE) and carried out by a non-governmental

organization (NGO) working on a contract basis. Each contracted NGO

will manage five pacts. The farmers who sign the pacts will receive

in-kind assistance valued at 2 million pesos (about US$1,000), and

will have access to credit and technical assistance (one technician

will be assigned to each 100 farmers). Infrastructure projects, such

as road building, are also foreseen. Farmers who do not eradicate

their crops within twelve months of receiving funds will face fumigation.

Peasants

who sign the pacts agree to eradicate their coca manually within twelve

months in exchange for funding, credit, and technical assistance for

the cultivation of legal crops. The agreements, signed with hundreds

of farmers in a single community, are managed by the Colombian government

alternative development agency (PLANTE) and carried out by a non-governmental

organization (NGO) working on a contract basis. Each contracted NGO

will manage five pacts. The farmers who sign the pacts will receive

in-kind assistance valued at 2 million pesos (about US$1,000), and

will have access to credit and technical assistance (one technician

will be assigned to each 100 farmers). Infrastructure projects, such

as road building, are also foreseen. Farmers who do not eradicate

their crops within twelve months of receiving funds will face fumigation. When

we came to Putumayo in mid-March, we found that not a cent had arrived

for those who had signed the pacts months earlier. Instead of an active

alternative development project, all we found were angry and discouraged

peasants. Because of a lengthy negotiation process with Fundaempresa,

the Cali-based NGO chosen to administer the first pacts, no aid had

been disbursed and nobody had contacted the signatories in Puerto

Asís and Santana to let them know what was happening.

When

we came to Putumayo in mid-March, we found that not a cent had arrived

for those who had signed the pacts months earlier. Instead of an active

alternative development project, all we found were angry and discouraged

peasants. Because of a lengthy negotiation process with Fundaempresa,

the Cali-based NGO chosen to administer the first pacts, no aid had

been disbursed and nobody had contacted the signatories in Puerto

Asís and Santana to let them know what was happening. Whether

true or not, news of this incident has spread throughout Putumayo,

weakening peasants’ will to enter into future pacts. (Gonzalo

de Francisco told us that if the incident did occur, which he doubted,

it was an error.) While de Francisco told us on March 13 that disbursements

of funds for the first pacts should begin in four weeks, in Putumayo

there is a growing sense that the peasants are being fooled yet again.

"It’s all pure bureaucracy, they’re going to waste

it all on per diems," a peasant leader told us. "It will

be like the hearts-of-palm plant all over again." On a few occasions,

we found ourselves in the odd position of defending the U.S. government

before angry farmers, assuring them that this time the aid had to

arrive because it was included in U.S. law.

Whether

true or not, news of this incident has spread throughout Putumayo,

weakening peasants’ will to enter into future pacts. (Gonzalo

de Francisco told us that if the incident did occur, which he doubted,

it was an error.) While de Francisco told us on March 13 that disbursements

of funds for the first pacts should begin in four weeks, in Putumayo

there is a growing sense that the peasants are being fooled yet again.

"It’s all pure bureaucracy, they’re going to waste

it all on per diems," a peasant leader told us. "It will

be like the hearts-of-palm plant all over again." On a few occasions,

we found ourselves in the odd position of defending the U.S. government

before angry farmers, assuring them that this time the aid had to

arrive because it was included in U.S. law. While

the pacts include manual eradication, they carry the threat of aerial

fumigation if coca plants are not pulled out in the agreed period.

The pacts allow producers to taper off coca-growing gradually over

twelve months, but most insist that the transition should be longer.

While coca can yield a first harvest within a few months, most other

crops will take longer, often well over a year, to bring in any income.

Most crops that thrive in the generally poor soils of lower Putumayo,

such as rubber, bananas, or hearts-of-palm, grow on trees that will

still be saplings after a year. Since 1999 the Municipal Rural Development

Commission of Puerto Asís, a prominent peasant group, has been promoting

a crop-substitution plan with a three-year tapering-off period. The

social pacts may risk failure unless the government either allows

signers to taper off coca-growing more gradually, or pays them a basic

wage while they await their first legal harvests.

While

the pacts include manual eradication, they carry the threat of aerial

fumigation if coca plants are not pulled out in the agreed period.

The pacts allow producers to taper off coca-growing gradually over

twelve months, but most insist that the transition should be longer.

While coca can yield a first harvest within a few months, most other

crops will take longer, often well over a year, to bring in any income.

Most crops that thrive in the generally poor soils of lower Putumayo,

such as rubber, bananas, or hearts-of-palm, grow on trees that will

still be saplings after a year. Since 1999 the Municipal Rural Development

Commission of Puerto Asís, a prominent peasant group, has been promoting

a crop-substitution plan with a three-year tapering-off period. The

social pacts may risk failure unless the government either allows

signers to taper off coca-growing more gradually, or pays them a basic

wage while they await their first legal harvests.