|

| Home | | |

Analyses | | |

Aid | | |

| |

| |

News | | |

| |

| |

| |

|

Last

Updated:6/23/05

|

|

CIP

International Policy Report: Peace - or "Paramilitarization?"

July 2005

Copies of this report are available for $2.50 each, or $1.00 each for orders of 20 or more, from the Center for International Policy. Request copies by e-mail at cip@ciponline.org. This report is also available in printer-friendly, easier-to-read Adobe Acrobat (.pdf) format. July 2005 Peace - or "Paramilitarization?" Why a weak peace agreement with Colombian paramilitary groups may be worse than no agreement at all By Adam Isacson At first glance, a negotiation between Colombia’s government and right-wing paramilitary groups looks easy and uncomplicated. The South American country’s paramilitary blocs (or “self-defense forces”) have always claimed to support the government. In particular, they claim to be ardent supporters of Colombia’s right-of-center president, Álvaro Uribe, who served as governor of a state where they are strong, and who owns land in zones under their total control.1

Even though their declared mission of defeating the FARC and ELN guerrillas is far from accomplished, in 2002 the AUC decided to consider going out of business. Its leaders were quick to accept President Uribe’s offer to negotiate their demobilization in exchange for a unilateral cease-fire. Uribe took office in August 2002; most paramilitary groups declared a cease-fire in December of that year. Though that cease-fire has been routinely violated – the Colombian government acknowledges 492 paramilitary killings, and non-governmental human rights groups claim thousands more – the talks have continued for over thirty months.2 Nonetheless, what many critics call a “negotiation between friends” has turned out to be far from easy. While both sides at the negotiating table may share an interest in a quick process that forgives most crimes and names few names, the same cannot be said of other stakeholders like victims’ groups, powerful members of Colombia’s Congress, and most international donor governments. Though they have no seats at the table, these sectors reject any deal that amnesties paramilitary leaders responsible for countless massacres and extrajudicial killings over the past twenty years. Many worry that the negotiations may help some of the country’s most notorious drug traffickers avoid punishment and keep most of their ill-gotten gains, including millions of acres of prime land taken by force. While failure to punish abuses or to right past wrongs risks prolonging Colombia’s generations-old cycle of violence, critics also point out that a weak agreement will leave paramilitary command and support networks in place, allowing the groups to continue to exist in some other form. The “framework law” for the talks: a bitter debate It was expected that the critics’ main leverage over these questions would be the law to manage the combatants’ demobilization, which Colombia’s Congress had to pass in order to allow an agrement to proceed. This “framework law” would determine whether paramilitary leaders had to serve time in prison for crimes against humanity. It would determine whether government prosecutors and investigators would have the time and the tools necessary to locate stolen assets, to settle victims’ claims for reparations, and to ensure that paramilitary networks are definitively stamped out. The AUC-government negotiations went on for two and a half years without such a law in place. Donor nations forced the issue, however, by requiring that an acceptable “framework law” be approved before they start writing checks to fund a demobilization and reintegration process that could cost upwards of a quarter of a billion dollars.3

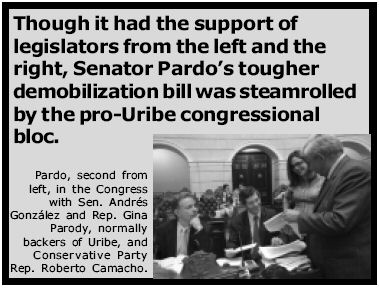

Other observers have speculated that key sectors of Colombia’s political and business elite, especially in paramilitary-dominated areas, would be threatened by a process that reveals too much about the rightist groups’ support and linkages, thus casting a light on their own role in backing the AUC’s anti-guerrilla dirty war. Since these sectors are an important base of President Uribe’s domestic support, this argument sustains, his negotiators have a strong incentive to pursue a peace agreement with as much “forgiving and forgetting” as possible. By late 2004 and early 2005, critics of this weak approach – ranging from human-rights groups to some prominent members of Colombia’s traditional political class – had lined up behind a much tougher alternative proposal, promoted by a coalition of legislators led by Senator Rafael Pardo, a former defense minister. By June 2005, however, President Uribe, his chief peace negotiator, Luis Carlos Restrepo, and their most ardent congressional supporters had thoroughly steamrolled the Pardo coalition’s proposals, pushing through a bill giving the paramilitary leadership much of what it wanted. The Colombian Congress passed the weaker bill on June 21. Instead of the five to ten years in prison called for by the Pardo bill, those found guilty of crimes against humanity would serve five to eight – likely in some form of “house arrest” at rural haciendas – minus credits for good behavior and time spent negotiating. Prosecutors would have only thirty days to gather evidence of responsibility for serious human-rights crimes, a period so short that the majority of massacres, disappearances, killings and forced displacements would likely go unpunished. “In 30 days one cannot do what couldn’t be done in ten years,” Senator Pardo objected in April.4 (The final version of the bill extended this period to a still-insufficient sixty days.) The Pardo bill would have required all demobilizing paramilitaries – from leadership to rank-and-file – to undergo a thorough interview requiring them to reveal not just their involvement in past crimes, but the assets they illegally obtained, where in the country they served, who commanded them, and who supported them, financially or otherwise. While this “exit interview” is far from a perfect tool for eliminating paramilitary networks, it was seen as a necessary step for effective prosecutions, location of stolen land and property, and eradication of paramilitary support networks. “To demand less would be to subordinate democracy to armed groups, whether new ones or old ones,” Senator Pardo wrote in February. “It would be to leave society with the message that crime does pay.”5 Yet even this requirement was stripped from the Uribe government’s bill, which merely calls on demobilizing paramilitaries to provide their names, towns of origin and similar contact information. Meanwhile, the government bill declares membership in a paramilitary group to be a “political crime.” Colombia’s constitution does not allow extradition to other countries for political crimes. Several top paramilitary leaders face indictments in U.S. courts for their role in sending drugs to the United States. If paramilitarism is considered a “political crime,” and the AUC leaders’ lawyers can successfully argue that their involvement in the drug trade was necessary to fund their cause, then they will never be tried in U.S. courts for shipping tons of cocaine to U.S. shores. Of all of these issues, jail terms have received the lion’s share of attention. On February 23rd, the AUC issued a communiqué letting it be known that they will quit the talks – “stay in the jungle and face war or death” – if the “framework law” includes jail time.6 If the law requires them to turn in their weapons only to report to prison, top AUC leader Iván Roberto Duque repeated in April, the paramilitaries will leave the talks. “If we have to decide to head back to the mountains, the first ones to feel sorry about this decision will be us, the AUC.”7 Dismantlement Despite these bombastic threats, the jail issue is a distraction from other, more serious issues. Jail time was not a key point of disagreement between the Uribe government and backers of the defeated Pardo bill, as both sides’ proposed prison terms differed by only a few years. Receiving less attention is a far broader and more vital difference between the Colombian government and its critics: call it the dismantlement question. In most peace processes, it is safely assumed that the armed group in question will disappear – or at least cease all illegal political activity – after negotiations conclude. This is not the case with the AUC talks. Though paramilitary leaders may end up with a clean slate and most past crimes forgiven, their power, and their ability to terrorize, may be largely unaffected. If they fail to do a thorough job of dismantling paramilitary command and support networks, then, negotiations with a weak “framework law” may in fact do more harm than good. Dismantlement is such an important issue that, if Colombia fails to include provisions to guarantee it, the Center for International Policy will be forced to recommend that the United States deny financial support to Colombia’s paramilitary demobilization process. To illustrate how important dismantlement is, consider two questions that, perhaps surprisingly, few are asking. First, what would happen if the talks fall apart? And second, would that outcome be worse than the result of a “successful” negotiation with a weak framework law? Return of the chainsaws? If the government-AUC talks break down, a common expectation is that, as more than one Colombian analyst has put it in conversations with CIP researchers, “volverán las motosierras” – “the chainsaws will return” – a reference to the tool paramilitary fighters have employed in some of their most grisly massacres. According to this scenario the paramilitaries will seek to make the talks’ breakdown as painful as possible, directing greatly stepped-up violence against the civilian population and demonstrating their ability to keep the state from governing territory.

Much of this positive result owes to two low-cost measures the Uribe government pursued upon taking office: a greater deployment of existing troops and police along roads and in population centers, and the paramilitaries’ declared cease-fire. While the AUC has not come close to respecting the cease-fire, even their partial observance has contributed strongly to the drop in violence levels.8 Should the cease-fire abruptly end, violence measures could begin to rise again, eroding or erasing one of President Uribe’s most-cited gains. The “chainsaw” scenario is an entirely possible one. It is unlikely to last for long, however. A wave of violence aimed at extracting concessions from the government can be expected to flame out. The AUC, a barely held-together collection of local warlords, has no paramount leadership at the moment. Divisions would deepen after the talks’ failure as many blocs, unwilling to see their lucrative illegal activities disrupted, will not adhere for long to a strategy aimed at posing a direct challenge to Colombia’s government. Due to its inherent nihilism, plus a strong likelihood that it would inspire a more determined opposition from the state security forces, a “chainsaw” response cannot sustain itself for long, if it happens at all. A new “mafia” Whether it follows a “chainsaw” phase or bypasses it entirely, the more likely scenario is the paramilitary blocs’ disintegration into mafia-like groups. After a failed negotiation, the AUC can be expected to devolve into regional structures of violence and criminality, especially drug-related crime. This has already begun, and it has accelerated since the negotiations began. The paramilitaries have had ties to the drug trade since their founding in the 1980s; they always counted drug lords among their principal donors, and increasingly raised money by participating in cocaine production and transshipment. Since about 2000-2001, however, their “narcotization” has reached greater depths. The top AUC leadership now includes several drug lords with no anti-guerrilla credentials, who have recently donned fatigues, christened themselves “comandante” and bought themselves paramilitary “franchises” – nominal command of small blocs – and seats at the negotiating table. Among them – there are several – is the AUC’s “inspector general,” Diego Fernando Murillo (nicknamed “Don Berna” or “Adolfo Paz”), an old Medellín cartel figure who later led the city’s feared network of hitmen-for-hire and street criminals; Víctor Manuel Mejía Múnera (nicknamed “the twin”), who has long been on FBI most-wanted lists as a high-ranking figure in the Northern Valle drug cartel; and Guillermo Pérez Alzate, or “Pablo Sevillano,” who is wanted by U.S. authorities for a shipment of 11 tons of cocaine. These drug-lord-turned-paramilitaries view Colombia’s guerrillas less as ideological enemies than as a rival crime syndicate. In fact, as examples of guerrilla-paramilitary combat grow ever scarcer, they are increasingly doing narco business with the guerrillas. “Every day we see that the border that existed between guerrillas and paramilitary groups has dissipated because of the drug-trafficking interests, the need to survive,” Col. Oscar Naranjo, director of the Colombian National Police investigative unit (DIJIN), told the Miami Herald last December.9 In February 2004, when Colombian troops captured “Sonia,” the “financial chief” of the FARC’s Southern Bloc, they found e-mails on her laptop asking the local AUC to lend a helicopter “to transport arms and drugs through the jungle.”10 In May 2005, Colombian authorities busted their biggest-ever shipment of drugs – fifteen tons of cocaine belonging to local FARC fronts, the AUC’s Liberators of the South bloc, and several narcotraffickers. Had he been trafficking drugs and killing enemies today, perhaps Pablo Escobar could have avoided ending up dead on a Medellín rooftop, surrounded by smiling, photo-snapping policemen. Today, he could have put on camouflage fatigues, dubbed himself “comandante” something-or-other, and bought himself a seat at the table in the Santa Fe de Ralito demilitarized zone, where negotiations are proceeding between the Colombian government and the AUC . There, Escobar would have stood a decent chance of winning amnesty, or at least a vastly reduced penalty, for his past crimes. His new status would also have stymied any U.S. attempt to extradite him.

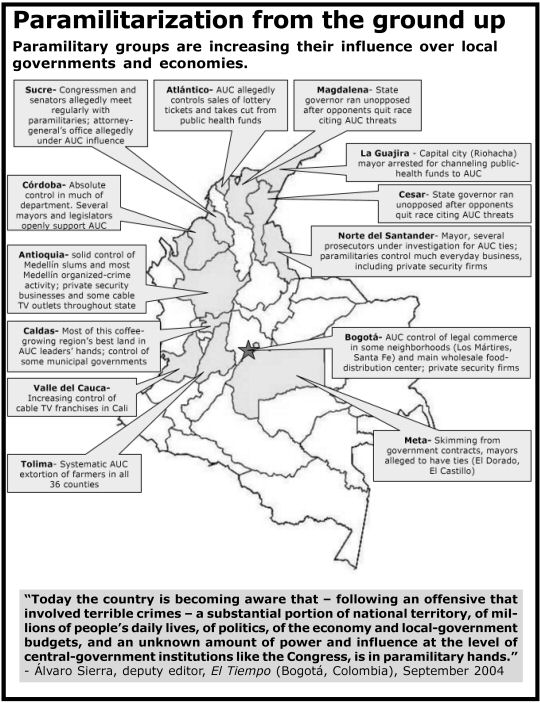

Takeover of the state Last September 26, Colombia’s main Sunday papers and newsweeklies all ran similar stories about the paramilitary-mafias’ creeping influence. “Alarms Sound About Advanced Symptoms of Paramilitarism in Colombia,” read the lead headline in El Tiempo, Colombia’s most-circulated daily.11 “According to a map drawn up by the Presidency of Colombia,” El Tiempo noted, “49 paramilitary blocs are present in 26 of the country’s 32 departments [provinces] and 382 of its 1,098 municipalities [counties]. This adds up to 13,500 men distributed across 35 percent of the national territory.”12 (Estimates of paramilitary strength range as high as 20,000.) What is remarkable about this presence today is how little it resembles the paramilitary model of five or six years ago, with thousands of members wearing uniforms, armbands and insignia, carrying heavy weapons, living with military discipline on remote encampments, and carrying out bloody offensives to expand into new territory. While there still are plenty of these truly “paramilitary” paramilitaries – especially in strategically (or narcotically) important rural zones – they are becoming obsolete, a throwback to the era of Carlos Castaño, the onetime paramount paramilitary leader who was forced out, and eventually killed, by members of the new wave of narco-paramilitary leaders. Instead, in the many regions of the country where their military control is uncontested (by the guerrillas or the military), the AUC’s blocs are increasingly coming to resemble Italian-style mafias. “In Colombia we may be entering an ‘a la italiana’ phase,” writes analyst Álvaro Camacho, “in which control and protection of illegal activity extends itself and accelerates, threatens free enterprise, overflows into politics and becomes a new form of organized crime that must be added to the already long list of threats to Colombian democracy.”13 Like Italy’s mafias, the paramilitaries are getting involved in politics in order to drain money from public coffers. Particularly in the northern part of the country, the paramilitaries have managed to get “their” candidates elected to governorships, mayor’s offices, town councils, university presidencies, and even Colombia’s Congress and Senate. This allows them to siphon off a lucrative cut of all government contracts and otherwise tap into municipal and departmental treasuries. While this is something that guerrillas have also done to fund themselves (such as the ELN’s access to oil royalties in Arauca department), the paramili-taries are taking over politics not in remote, neglected zones, but in some of Colombia’s principal population centers. Unlike Italian mafiosi, though, the paramilitaries also seem to be getting involved in politics for its own sake. Many blocs have developed a social discourse (if not an ideology) that – while it stresses order, tradition and property – includes so much populist advocacy for the poor, including calls for land reform, that it sounds a bit like the guerrillas’ rhetoric. Paramilitary “foundations,” meanwhile, are paying for road-building, health services and development projects in much of northern Colombia.

Arias and Pineda belong to a new political party, “Colombia Viva,” many of whose members express open support for the paramilitaries. The party includes thirteen members of the Congress, 27 mayors and 388 town councilmembers. Many other paramilitary-backed (or paramilitary-controlled) politicians belong to Colombia’s traditional parties. The mere fact that paramilitary supporters are participating in the democratic process is not necessarily bad news – a measure of success working “within the system” could be an incentive for all armed groups to choose the ballot box over the rifle. The trouble is, just as guerrilla groups did in the past with disastrous results, the paramilitaries are choosing both. “The paramilitaries are forging ties with the Colombian political class even here, in this Congress, while they kill people along the length and breadth of the country,” warned Rep. Gustavo Petro, a former member of the disbanded M-19 guerrillas, in an October 2004 congressional debate. “What is being built in Colombian territory are ‘death clubs’ that kill opponents.”14 The paramilitaries’ “combination of all forms of struggle” goes well beyond electoral power and violence against political opponents. Like any proper mafia, the AUC’s blocs have increased their control over much of Colombia’s illegal economy. Not just the drug trade (of which, according to U.S. Ambassador William Wood, they control about 40 percent), but a big share of contraband smuggling, counterfeiting, prostitution, and gang activity.15 Extortion is a major illegal income source. A “high-level security-force source” told El Tiempo about this phenomenon in the Caribbean port city of Santa Marta, which extends “from the 1,000 pesos (40 cents) they charge each street vendor in Santa Marta to the 250,000 to 500,000 ($100 to $200) that every truck that enters the port must pay … and we’re talking about ships that need 70 trucks to unload them.”16 Recently, the paramilitaries have begun to expand their income from Colombia’s legal economy. They are increasing their share of local-government contracts, especially funds from the Subsidized Regimen Administration (ARS), a program of block grants from the central government to provide health care for the poorest. Colombian authorities are investigating as many as 63 cases of ARS funds being diverted to the paramilitaries.17

This model of encroachment on the state and legal economy, combined with continued violent territorial control in league with longtime supporters, may point the way to the future of right-wing violence in Colombia. As mafias in league with landowners, ranchers, drug lords and other monied interests, ex-paramilitaries may no longer need to maintain costly “self-defense groups.” Instead, the near future may see the AUC’s component blocs evolve into dangerous hybrids of organized-crime syndicate and death squad, something similar to the so-called “hidden powers” that have come to dominate much of post-conflict Guatemala.18 Loose networks of wealthy individuals, sectors of the military, criminals and former armed-group members will benefit from corruption, threaten and kill would-be reformers such as human rights activists and union leaders, dominate local media, carry out “social cleansing” campaigns against street criminals, drug addicts, prostitutes and other “undesirables,” and even provide social services through their own non-governmental organizations. Much of rural Colombia is already represented by corrupt political bosses who govern through patronage and backroom, machine politics. If the AUC’s new version of “combination of all forms of struggle” serves them well, this old guard may soon be replaced by a new class of corrupt political bosses. The new congressmen, senators, governors and mayors they elect would be quite different from the political-machine hacks of old. They would be part of a national political project: one that is vaguely right-wing, intimately tied to the drug trade and other criminal networks, represents the interests of a Paleolithic large-landholding class, and freely uses violence when the political process gets in the way of their agenda. If their “armed campaigning” allows them to increase their share of control over government institutions – if the “para-state” is allowed to grow within the state – Colombia will finally become the “narco-democracy” that U.S. drug warriors have worried about for so long. Is a breakdown better than a bad peace agreement? Though the mafia scenario suggested here describes what might happen after a breakdown of negotiations, it may be the exact outcome that the paramilitary leadership hopes to gain from a peace agreement, too. It strains the imagination to think that AUC leaders with long histories in Colombia’s criminal underworld – figures like Don Berna, “Jorge 40” or “Macaco” – truly plan to retire and pursue new lives as gentleman farmers or local politicians. If that were their true goal, it would not be greatly hindered by a negotiated settlement that first puts them in jail for several years, takes away their ill-gotten assets, and requires their rank-and-file to reveal details about their organization. Nonetheless, the paramilitary leadership vociferously opposes such measures; its communiqués have nothing but angry words for Senator Pardo and others who have pushed for tougher measures. If the paramilitary leadership gets most of the impunity it wants, with no questions asked, from the negotiations, its transition to a mafia or “hidden powers” model will face few obstacles. The same hard-right landowning and narcotrafficking interests that helped establish today’s paramilitaries would continue to seek a way to keep guerrillas at bay and the political left weak and intimidated. The warlords who comprise today’s AUC leadership – including the recently arrived narcotraffickers who would most benefit from a non-extradition guarantee – would continue to profit from illegal activity (drugs, counterfeiting, smuggling, kidnapping and extortion) and to make inroads into the state and the legal economy.

In other words, a lenient negotiated agreement – one based on a weak “framework law” that gives the paramilitaries much of what they want – would have virtually the same result as a premature rupture in the talks. The main difference would be in the short term, as a rupture carries a risk of a short-term burst of violence (the “chainsaw” scenario) in its immediate aftermath. Otherwise, a weak peace agreement that fails to stop Colombia’s paramilitarization would yield the same outcome as no peace agreement at all. The importance of a clear U.S. (and international donor) position The implication of all this is clear: if the paramilitary leadership shows no flexibility on issues like punishment, accountability, reparations and dismantlement, it would not be tragic to let the talks collapse. It makes sense for the Colombian government to take a far tougher negotiating position than it has to date.

Taking a tougher line on paramilitary dismantlement, and risking a breakdown in talks, of course carries a political cost. The penalty for failure at the negotiating table grows ever higher as May 2006 elections approach and President Uribe seeks a second term (if Colombia’s Supreme Court upholds a constitutional change allowing him to stand for re-election). This cost can be reduced – and the Uribe government’s resolve can be strengthened – if the United States and other international donors send a clear message that they will not support a process that legalizes a new mafia-plus-death-squad power structure in Colombia. By doing so, they can offer badly needed leverage to Colombians doing the difficult work of trying to prevent a negotiation process that ends up legitimizing paramilitariz-ation. While the prospect of disarming and reintegrating thousands of paramilitary fighters – most of them poor young men with few opportunities – is a promising one, donor nations must make clear that it must not go hand-in-hand with a deal that fails to dismantle paramilitarism. Peace will not result if murderers and drug-dealers are able to legalize their de facto power. As of mid-2005, the Bush administration has not said this clearly. Some officials have insisted, as now-retired Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs Marc Grossman did in February, that the Colombian framework law “should guarantee the dismantlement of the AUC, stop its financing and confiscate its properties.” But the administration is clearly anxious to avoid disagreements with Álvaro Uribe – its closest ally in Latin America – and its tone softened as it became evident that the “framework law” coming out of Colombia’s Congress would be a weak one. According to the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ summary of U.S. Ambassador William Wood’s remarks at a June 14 event, the ambassador “described the Uribe government’s goal in the AUC peace process as reducing violence against the innocent. He argued that the human rights debate in Colombia had shifted away from the protection of the innocent to the punishment of the guilty. ‘Bad guys’ were going to get more out of the peace process than they deserved, he maintained, but innocent people were also likely to get from the peace process what they so desperately needed. To what degree were people willing to put peace at risk, he asked, for stricter standards of justice?”

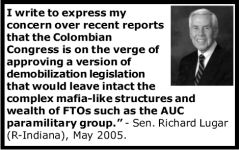

The U.S. line on paramilitarization must become significantly tougher, even if it means open disagreement with President Uribe. In fact, the Bush administration would do well to heed the advice of the U.S. Congress, including prominent Republicans in both houses. “We believe it is crucial that paramilitaries seeking benefits from demobilization be required to first disclose fully their knowledge of the operative structure of these FTOs [Foreign Terrorist Organizations] and the role of individual members in illegal activities, and to forfeit their illegally acquired assets,” read a bipartisan February 2005 letter to President Uribe signed by the Republican chairmen of both the House International Relations Committee (Henry Hyde of Illinois) and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (Richard Lugar of Indiana). Senator Lugar followed up in May with a letter to Uribe expressing concern “that the Colombian Congress is on the verge of approving a version of demobilization legislation that would leave intact the complex mafia-like structures and wealth of FTOs such as the AUC paramilitary group.” This is the sort of clear, unequivocal message about paramilitary dismantlement that should be coming from the executive branch. If the Bush administration ultimately lacks the political will to send this message, it will be up to the U.S. Congress to make sure that no taxpayer dollars go to support a demobilization process that whitewashes paramilitary power and sets back the rule of law in Colombia. ___________________________

Endnotes 1

President Uribe reportedly maintains 1,000 head of cattle and

sixty purebred horses at his ranch, “El Ubérrimo,” located in

the municipality of Montería, the paramilitary-dominated capital

of the paramilitary-dominated department (province) of Córdoba.

Reporter Gonzalo Guillén of Miami’s El Nuevo Herald notes

that several paramilitary leaders, “among them Salvatore Mancuso,

own large extensions of land in Córdoba department, and some

are neighbors of ‘El Ubérrimo’ hacienda.” 2 “Van 492 homicidios durante tregua de Auc,” Efe, El Colombiano

(Medellín, Colombia: June 18, 2005) <http://www.elcolombiano.terra.com.co/BancoConocimiento/V/van_492_homicidios_durante_tregua_de_auc/van_492_homicidios_durante_tregua_de_auc.asp?CodSeccion=7>. 3 See, for instance, Presidency of Colombia, “Texto de las conclusiones del Consejo de la Unión Europea sobre Colombia“ (Bogotá: December 13, 2004) <http://www.presidencia.gov.co/sne/2004/diciembre/13/06132004.htm>. 4 “Proyecto de justicia y paz llevará a un modelo político basado en el crimen organizado: Rafael Pardo,” El Tiempo (Bogotá: April 9, 2005) <http://200.41.9.39/coar/NEGOCIACION/negociacion/ARTICULO-WEB-_NOTA_INTERIOR-2032331.html>. 5 Rafael Pardo, “La esencia del paramilitarismo no se está desmontando,” El Tiempo (Colombia: February 2, 2005) <http://eltiempo.terra.com.co/opinion/colopi_new/columnas_del_dia/ARTICULO-WEB-_NOTA_INTERIOR-1959450.html>. 6 United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, “Nuestra verdad ante el país y el mundo” (Colombia: February 23, 2005) <http://www.colombialibre.org/detalle_col.php?banner=editorial&id=10577>. 7 Javier Baena, “Proposed law endangers talks in Colombia,“ Associated Press, The Miami Herald (Miami: April 11, 2005) <http://www.miami.com/mld/miamiherald/news/world/americas/11361806.htm>. 8 “Denuncian 342 violaciones al cese al fuego por ‘paras’,” Colprensa

news service, El País (Cali, Colombia: October 3, 2004)

<http://elpais-cali.terra.com.co/paisonline/notas/Octubre032004/paras.html>. 9Steven Dudley, “Paramilitaries ally with rebels for drug trade,” The Miami Herald (Miami: November 25, 2004) <http://www.miami.com/mld/miamiherald/news/front/10268889.htm>. 10 “Computador decomisado a las Farc contiene indicios de red internacional de narcotráfico,” El Tiempo (Bogotá: March 10, 2004) <http://www.eltiempo.com/coar/NARCOTRAFICO/narcotrafico/ARTICULO-PRINTER_FRIENDLY-_PRINTER_FRIENDLY-1548443.html>. 11 “Se prenden las alarmas por síntomas avanzados de paramilitarización de Colombia,” El Tiempo (Bogotá: September 26, 2004) <http://eltiempo.terra.com.co/coar/ANALISIS/analisis/ARTICULO-WEB-_NOTA_INTERIOR-1804722.html>. 12 “Se prenden las alarmas,” El Tiempo, op.cit. 13 Álvaro Camacho Guizado, “Paramilitarismo y mafia,” El Espectador (Bogotá: October 3, 2004) <http://www.elespectador.com/2004/20041003/opinion/nota16.htm>. 14 Constanza Vieira, “Paramilitaries Extend Their Tentacles,” Inter-Press Service (Bogotá: October 16, 2004) <http://www.ipsnews.net/interna.asp?idnews=25838>. 15 Amb. William B. Wood cited in International Crisis Group, Demobilising the Paramilitaries in Colombia: An Achievable Goal? (Brussels: ICG, August 5, 2004) <http://www.crisisgroup.org/home/index.cfm?id=2901&l=1>. 16 “Se prenden las alarmas,” El Tiempo, op. cit. 17 “Raponazo de los paras al erario público,” El Espectador (Bogotá: September 26, 2004) <http://www.elespectador.com/2004/20040926/periodismo_inv/2004/septiembre/nota4.htm>. 18 See Susan Peacock and Adriana Beltrán, Hidden Powers in Post-Conflict Guatemala (Washington: Washington Office on Latin America, December 2003) <http://www.wola.org/publications/guatemala_hidden_powers_full_report.pdf>. 19 Government of Colombia, High Commissioner for Peace, “Entrevista del alto comisionado para la paz, Luis Carlos Restrepo en ‘Pregunta Yamid’” (Bogotá: February 4, 2005) <http://www.altocomisionadoparalapaz.gov.co/noticias/2005/febrero/feb_09_05b.htm>. A publication of the Center for International Policy © Copyright 2005 by the Center for International Policy. All rights reserved. Any material herein may be quoted without permission, with credit to the Center for International Policy. |

|

|

| Asia | | |

Colombia | | |

| |

Financial Flows | | |

National Security | | |

| Center

for International Policy |

The

Colombian military itself helped to found the groups over twenty

years ago, as part of a brutal strategy to undermine, through

systematic attacks on civilian populations, the leftist guerrillas

that have dominated much of rural Colombia since the mid-1960s.

Though declared illegal in 1989, the paramilitaries – loosely

confederated in a 20,000-strong national organization, the United

Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) – continue to benefit

all too frequently from military logistical support, advice,

or toleration.

The

Colombian military itself helped to found the groups over twenty

years ago, as part of a brutal strategy to undermine, through

systematic attacks on civilian populations, the leftist guerrillas

that have dominated much of rural Colombia since the mid-1960s.

Though declared illegal in 1989, the paramilitaries – loosely

confederated in a 20,000-strong national organization, the United

Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) – continue to benefit

all too frequently from military logistical support, advice,

or toleration. The

Uribe government had already introduced two earlier bills (in

August 2003 and April 2004) that were widely criticized for

being too lenient, allowing near-total amnesty for paramilitary

leaders, and doing almost nothing to require the groups to dismantle

their command and support structures. Uribe administration officials

argued that a law that asks too much of paramilitary leaders

would make it impossible to move ahead in negotiations.

The

Uribe government had already introduced two earlier bills (in

August 2003 and April 2004) that were widely criticized for

being too lenient, allowing near-total amnesty for paramilitary

leaders, and doing almost nothing to require the groups to dismantle

their command and support structures. Uribe administration officials

argued that a law that asks too much of paramilitary leaders

would make it impossible to move ahead in negotiations.  A

renewed wave of massacres, homicides and disappearances would

be a horrifying tragedy. It would also deal a severe blow to

the Uribe government’s signature “Democratic Security” program,

which is credited with bringing reductions in many statistical

measures of violence in Colombia. Since Uribe took office in

August 2002, official data show reductions in murders, kidnappings,

acts of sabotage and attacks on populations. Though the apparent

progress has slowed in 2005, with guerrilla attacks registering

a sharp increase, Colombia is considered somewhat less dangerous

than it was four years ago.

A

renewed wave of massacres, homicides and disappearances would

be a horrifying tragedy. It would also deal a severe blow to

the Uribe government’s signature “Democratic Security” program,

which is credited with bringing reductions in many statistical

measures of violence in Colombia. Since Uribe took office in

August 2002, official data show reductions in murders, kidnappings,

acts of sabotage and attacks on populations. Though the apparent

progress has slowed in 2005, with guerrilla attacks registering

a sharp increase, Colombia is considered somewhat less dangerous

than it was four years ago.

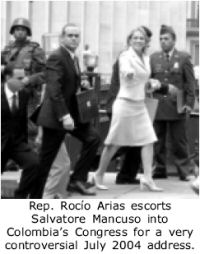

After

the 2002 legislative elections, paramilitary leader Salvatore

Mancuso boasted that the AUC controlled at least 30 percent

of the Colombian Congress. While not all of these legislators

are willingly doing the paramilitaries’ bidding, a few are enthusiastic

backers. The most visible are Rocío Arias and Eleonora Pineda,

who represent paramilitary strongholds in northern Antioquia

and southern Córdoba departments. Arias and Pineda were the

driving force behind a controversial July 2004 address to the

Congress by paramilitary leaders Mancuso, Duque and Ramón Isaza.

After

the 2002 legislative elections, paramilitary leader Salvatore

Mancuso boasted that the AUC controlled at least 30 percent

of the Colombian Congress. While not all of these legislators

are willingly doing the paramilitaries’ bidding, a few are enthusiastic

backers. The most visible are Rocío Arias and Eleonora Pineda,

who represent paramilitary strongholds in northern Antioquia

and southern Córdoba departments. Arias and Pineda were the

driving force behind a controversial July 2004 address to the

Congress by paramilitary leaders Mancuso, Duque and Ramón Isaza. Like

drug cartels before them, paramilitary groups are setting up

their own companies to provide services like private security

and cable television in urban areas. Competitors are being run

out of business – and not by the paramilitary companies’ superior

service or low prices.

Like

drug cartels before them, paramilitary groups are setting up

their own companies to provide services like private security

and cable television in urban areas. Competitors are being run

out of business – and not by the paramilitary companies’ superior

service or low prices. The

Colombian government’s top peace negotiator, Luis Carlos Restrepo,

has said that to do so – for instance, to adopt the Pardo bill’s

provisions – would have made it impossible for him to negotiate

with the AUC leadership: “Simply through mere persuasion, I

cannot convince people to come to a concentration zone and demobilize

if all of them, without exception, are to be judged.”19

Though he threatened to resign in February rather than be forced

to negotiate under a tougher law – a gambit that apparently

helped win him a weaker law – Restrepo’s complaint was off the

mark. If a weak agreement is likely to bring roughly the same

result as a collapse, Restrepo need not bend so far to keep

the talks alight.

The

Colombian government’s top peace negotiator, Luis Carlos Restrepo,

has said that to do so – for instance, to adopt the Pardo bill’s

provisions – would have made it impossible for him to negotiate

with the AUC leadership: “Simply through mere persuasion, I

cannot convince people to come to a concentration zone and demobilize

if all of them, without exception, are to be judged.”19

Though he threatened to resign in February rather than be forced

to negotiate under a tougher law – a gambit that apparently

helped win him a weaker law – Restrepo’s complaint was off the

mark. If a weak agreement is likely to bring roughly the same

result as a collapse, Restrepo need not bend so far to keep

the talks alight. This

line of argument, which focuses more on punishment than dismantlement,

misses the point entirely. By failing to dismantle paramilitarism,

the negotiation process in its current form will do far more

“to put peace at risk.” Greater hope for peace lies in an agreement

creating strong mechanisms for dissolving the shady nexus of

paramilitaries, drug lords, large landholders, crooked politicians

and military hardliners for whom a weak peace agreement will

be a key step toward greater power. Not to mention avoidance

of extradition to the United States.

This

line of argument, which focuses more on punishment than dismantlement,

misses the point entirely. By failing to dismantle paramilitarism,

the negotiation process in its current form will do far more

“to put peace at risk.” Greater hope for peace lies in an agreement

creating strong mechanisms for dissolving the shady nexus of

paramilitaries, drug lords, large landholders, crooked politicians

and military hardliners for whom a weak peace agreement will

be a key step toward greater power. Not to mention avoidance

of extradition to the United States.