|

| Home | | |

Analyses | | |

Aid | | |

| |

| |

News | | |

| |

| |

| |

| Last

Updated:12/14/00 |

| "Steel

Magnolias:" adjusting to reality in Putumayo, by Abbey Steele and Adam

Isacson, December 14, 2000 "Steel

Magnolias:" adjusting to reality in Putumayo

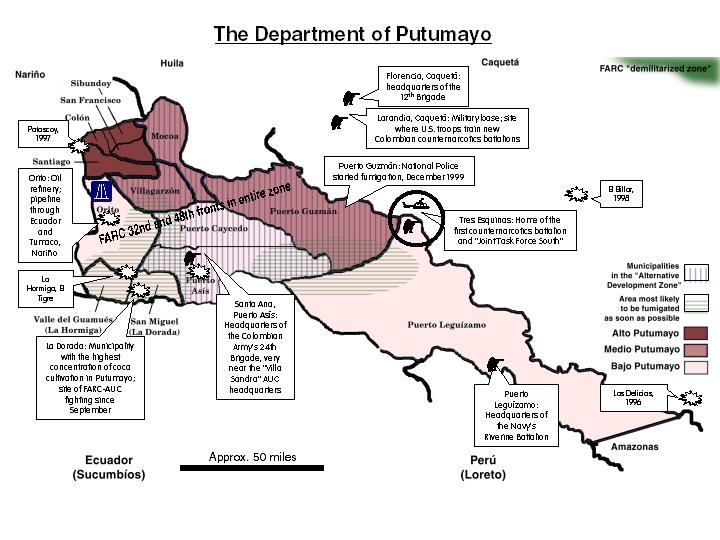

By Abbey Steele and Adam Isacson December 14, 2000 Two Saturdays ago María Inés Restrepo, the director of Colombia's alternative development agency (PLANTE), pulled out several coca plants and symbolically replaced them with a newly planted magnolia tree. The ceremony took place in Santa Ana, a village just north of Puerto Asís, the largest town in the Maryland-sized department of Putumayo. Overrun by guerrillas and paramilitaries, Putumayo - in southwest Colombia along the border with Ecuador - is home to well over 100,000 acres of coca, the plant used to make cocaine. The tree-planting commemorated the first of several planned "community pacts" designed to wean local peasants away from the coca trade. Six days later, at the Larandia military base less than 100 miles north of Santa Ana, U.S. Special Forces applauded and videotaped the graduation of the Colombian Army's second counternarcotics battalion. As the New York Times reported, "soldiers in camouflage face paint and black berets marched through a cloud of yellow, blue and red smoke - the colors of the Colombian flag - toward the generals at the reviewing stand." The new battalion will be based in Tres Esquinas, on the border between Colombia's departments of Caquetá and Putumayo, about 50 miles away from the site of the previous Saturday's tree-planting. Both the magnolias and the battalion were made possible by the United States, as part of its contribution to "Plan Colombia," Bogotá's $7.5 billion plan to attack the drug trade and strengthen state institutions. Washington insists that this two-pronged carrot-and-stick program will eradicate coca in Putumayo department and help pacify Colombia. Most of the U.S. aid - military and otherwise - is focused on Putumayo. But there are strong reasons to be concerned that the situation "on the ground" in Putumayo may undermine the ambitious U.S.-funded programs. The "push into southern Colombia" and the "community pacts" More than half of the U.S. contribution funds the recruiting and training of three new battalions like the one inaugurated last week, eventually to number about 2,800 troops. The units are being equipped with dozens of helicopters, both refurbished Vietnam-era Hueys and sophisticated new $15 million Blackhawks. The "Push into Southern Colombia" - the name given to the battalions' operation - seeks to "establish the security conditions" necessary to carry out anti-drug operations, such as aerial fumigation with glyphosate, the active chemical in the commercial weed-killer "Round-Up." Of course, the only threat to "security conditions" in this area is posed by Colombia's FARC guerrillas, which shoot back at fumigation planes. Making this connection, it becomes clear that the United States is funding operations against Colombian guerrillas for the first time.

U.S. and Colombian officials insist that - for now, at least - the "push" and the fumigations will take place only in remote areas of Putumayo with a high concentration of coca plantations in excess of 3 hectares (7.5 acres). They insist as well that these "industrial" coca areas are largely uninhabited (except, of course, for thousands of landless rural workers who survive by picking coca leaves for meager wages). It is still unclear what parts of Putumayo make up this zone of "industrial" coca-cultivation; "targeting decisions" for fumigation are still being made, the State Department's Rand Beers told a congressional committee in October. In areas where coca cultivations are generally less than 3 hectares, the U.S. and Colombian governments plan to employ the "carrot," at least for a limited time. These "family farmers" will be given the opportunity to enter into "community pacts" like the agreement commemorated at the December 2 tree-planting in Santa Ana. Under the pacts, peasants will be given financial and technical assistance to switch to legal crops, in exchange for manually eradicating their coca within twelve months. The community-pact program, first being implemented in Puerto Asís municipality, is to spread to the nearby municipalities of Mocoa, Villagarzón, Puerto Guzmán, and Puerto Caycedo in central Putumayo. The Colombian government official responsible for "social" assistance in Putumayo, Gonzalo de Francisco, explained, "We are interested in signing pacts … but if [the farmers] are just pulling our leg, the repressive options are always open." Small farmers who do not eradicate their coca in twelve months will face the "repressive option" of fumigation. Escalating violence This plan sounds neat and tidy on the surface - help the small farmers and spray the big ones. But an upsurge in violence over the past several months indicates that things may not be so easy. On November 16, Colombia and the United States announced that the fumigation of "industrial" coca in Putumayo - originally scheduled to begin in December - had been postponed until January. This is largely due to the department's rapidly deteriorating security situation. The Colombian government has never controlled Putumayo since non-indigenous people began settling there a few decades ago. The FARC moved its 32nd front into the area in the mid-1980s, increasing its presence with the mid-1990s arrival of its 48th front. The guerrillas routinely bomb oil pipelines, forcibly recruit young people, carry out extra-judicial executions, and profit from the drug trade by taxing coca-growing peasants. The right-wing paramilitaries (the AUC, or United Self-Defense Forces, led by Carlos Castaño) arrived in large numbers at the beginning of 1998, when fighters from its outposts in northwestern Colombia announced their presence with bloody massacres in Puerto Asís, Orito, La Hormiga and other towns. Generally, the paramilitaries control major town centers, but the FARC continues to dominate rural areas. By most estimates, the FARC currently maintains about 2,000 fighters in Putumayo, and is able to deploy thousands more from elsewhere, particularly the demilitarized zone in Meta and Caquetá departments to the north. Because they have been in the area longer, the FARC are more familiar with the terrain and the local residents, who are a key source of intelligence. According to many reports, the guerrillas are also arming many peasants and forcing them to take eight days of training in anticipation of the coming U.S.-funded offensive. For their part, the paramilitaries have been steadily increasing their presence in Putumayo, currently estimated at about 600 fighters. Colombia's military is also present in Putumayo; the 24th Brigade is based in Santa Ana, a Navy Riverine Brigade (created with U.S. funds in the late 1990s) is headquartered in Puerto Leguízamo, and the new counternarcotics battalions are at Tres Esquinas. The military-paramilitary connection The Colombian military rarely confronts the paramilitaries in Putumayo, and is widely accused of aiding and abetting them. Paramilitaries walk through most Putumayo towns openly and unmolested. Some even boast to reporters that they are former army soldiers. The paramilitary headquarters in Puerto Asís, an estate called "Villa Sandra," is located a short distance away from the 24th Brigade's headquarters. In August, the BBC's Jeremy McDermott discussed the ease with which he located the "paras" at Villa Sandra:

In October, a bold police officer denounced military-paramilitary cooperation in Puerto Asís to local civilian authorities. According to the Bogotá daily El Tiempo, the policeman reported that the paramilitaries blatantly identify themselves with insignia and move easily in clearly marked vehicles. The policeman said he did not understand "the abilities and skills that they use to make a mockery of the Army's roadblocks, and to station themselves right in front of them." He added that he has heard numerous charges that the local army command meets regularly with paramilitary leaders at Villa Sandra. A government official quoted in the Houston Chronicle on October 15 commented that "cooperation is very close," noting that the paramilitary headquarters is only two blocks from the town's military base. Puerto Asís Mayor Manuel Alzate asked the Chronicle, "How is it possible that we are under siege and the army doesn't do anything?" The FARC's armed strike The FARC and AUC have been vying, frequently by violent clashes, for control of narcotics industry profits, and violence has escalated enormously in the last few months. Civilians are literally caught in the crossfire. By early November, fighting in Putumayo had forced about 4,500 people to leave Putumayo for Ecuador, Cali, neighboring Nariño and Huila departments, and even to Bogotá, 300 miles to the north. At least 450 so far (a low estimate) are seeking refuge in Ecuador. The violence intensified on September 21, when about 200 paramilitaries attacked La Dorada, the main town of San Miguel municipality. The FARC retaliated, leaving La Dorada's 5,600 inhabitants surrounded. While skirmishes are frequent, the paramilitaries still occupy La Dorada. They are reportedly carrying out brutal "cleansing" tactics to rid the area of suspected guerrilla allies. Colombia's security forces have played little role in the La Dorada fighting. Three days after the attack on La Dorada, the FARC launched something they called an "armed strike." For months, FARC fighters banned all vehicle traffic throughout Putumayo. Guerrilla roadblocks confiscated and destroyed all cars, buses or trucks they encountered. The "strike" sharply reduced access to food, water and basic necessities, causing a severe humanitarian crisis in outlying areas. By early November, the government had airlifted about 300 tons (much less, insisted local officials) of rice, milk, beans, cooking oil, and other food items to the region. Nonetheless, Interior Ministry spokesman Raúl Gutiérrez admitted, "We have only gotten the food to the big towns." The FARC had said that the strike would only be lifted if the Colombian government called off the U.S.-supported military offensive foreseen under Plan Colombia. For reasons that remain unclear, the guerrillas relented on December 9, unilaterally lifting the siege after 79 days. "Showcase" operations? The "armed strike" and the paramilitaries' unchallenged presence vividly illustrate the Colombian security forces' inability to affect illegal armed groups' dominance of Putumayo. If the government cannot deliver humanitarian aid to rural areas or confront the AUC, it is fair to ask whether it can guarantee "community pacts" in Putumayo or "secure" coca-growing areas for its aerial fumigation program. It is also fair to ask whether inserting the counter-narcotics battalions - 2,800 soldiers with a few months of U.S. training and helicopters that have yet to arrive - will make a significant tactical difference. Rep. Benjamin Gilman (R-New York), the chairman of the House International Relations Committee, echoed these doubts in a November 14 letter to "Drug Czar" Barry McCaffrey:

The Clinton and Pastrana administrations do not appear to share these doubts. "Far from being a failure of Plan Colombia, this is exactly why you need it," Assistant Secretary of Defense Brian Sheridan told the St. Petersburg Times in November. "Putumayo is a poster child for why you need Plan Colombia. The FARC and the paramilitaries are running roughshod all over the Putumayo right now, killing each other, blockading roads, holding villages hostage … and the military and the police are nowhere to be found." Pastrana's point man for Plan Colombia, Jaime Ruiz, told the Washington Post, "It sounds like you'd have to secure the area before you begin the projects, but the truth is, you do both at the same time. We are trying to convince the population that we can do this without force, but they are afraid to trust the government and end up with nothing, so this first step is very interesting." These first steps are being delayed, however, by the security situation in Putumayo. Magnolia plantings aside, the "community pacts" are off to a shaky start: "the presence of the armed units of the guerrillas and the paramilitaries is going to make it more difficult to start more than a few pilot projects," Undersecretary of State Thomas Pickering told reporters in November. While two counter-narcotics battalions have already graduated, the launch of their "push into southern Colombia" has been postponed for one month. For now, at least, it appears that the situation in Putumayo is more complicated than planners in Washington and Bogotá had anticipated. Policymakers, particularly the incoming Bush administration, should take advantage of the resulting delay to carry out a fundamental re-thinking of the United States' approach to helping Colombia. |

||

|

|

| Asia | | |

Colombia | | |

| |

Financial Flows | | |

National Security | | |

| Center

for International Policy |