Military Spending: A Poor Job Creator

Fact Sheet by William D. Hartung

Arms & Security Project

September 2011

Plans for cutting the federal deficit have raised an important question: what impact would military spending reductions have on jobs?

Contrary to the assertions of the arms industry, maintaining military spending at the expense of other forms of federal expenditures would actually result in a net loss of jobs. This is because military spending is less effective at creating jobs than virtually any other form of government activity.

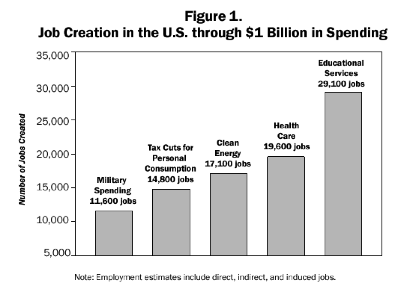

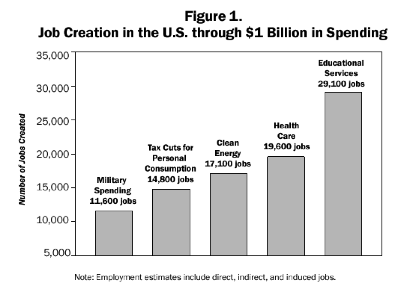

Source for chart: Robert Pollin and Heidi Garrett-Peltier, “The U.S. Employment Effects of Military and Domestic Spending Priorities,” Department of Economics and Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts, October 2009.

The question is not whether military spending creates jobs – it is whether more jobs could be created by the same amount of money invested in other ways. The evidence on this point is clear.

- A billion dollars devoted to a tax cut creates 25% more jobs than a billion dollars of military spending;

- Spending on clean energy production produces one and one-half times more jobs ;

- and spending on education creates two and one-half times more jobs.

And though average overall compensation is higher for military jobs than the others, these other forms of expenditure create more decent-paying jobs (those paying $64,000 per year or more) than military spending does. 1

Part of the reason that military spending creates fewer jobs than other forms of expenditure is that a large share of that money is either spent overseas or spent on imported goods. By contrast, most of the money generated by spending in areas like education is spent in the United States.

In addition, more of the military dollar goes to capital, as opposed to labor, than do the expenditures in the other job categories. For example, only 1.5% of the price of each F-35 Joint Strike Fighter pays for the labor costs involved in “manufacturing, fabrication, and assembly” work at the plane’s main production facility in Fort Worth, Texas. 2 A full 85% of the F-35s costs go for overhead, not for jobs actually fabricating and assembling the aircraft. 3

In a climate in which deficit reduction is the central focus of budget policy in Washington, a dollar spent in one area is likely to come from cuts in other areas. The more money we spend on unneeded weapons programs, the more layoffs there will be of police officers, firefighters, teachers and other workers whose jobs are funded directly or indirectly by federal spending.

---------------

2. U.S. Committee on Armed Services, “Hearing to Receive Testimony on the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Program in Review of the Defense Authorization Request for Fiscal Year 2012 and Future Years Defense Program,” May 19, 2011, p. 14.

3. Andrea Shalal-Esa, “Lockheed, Pentagon Vow to Attack F-35 Costs,” Reuters.com, May 12, 2011

|