|

| Home | | |

Analyses | | |

Aid | | |

| |

| |

News | | |

| |

| |

| |

| Last

Updated:12/13/02 |

| Testimony

of Adam Isacson, Center for International Policy, House Committee on Government

Reform, December 12, 2002 Testimony of Adam

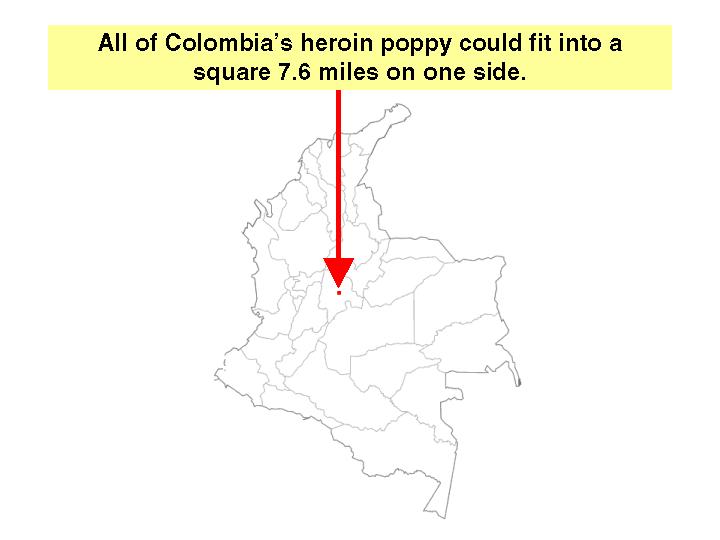

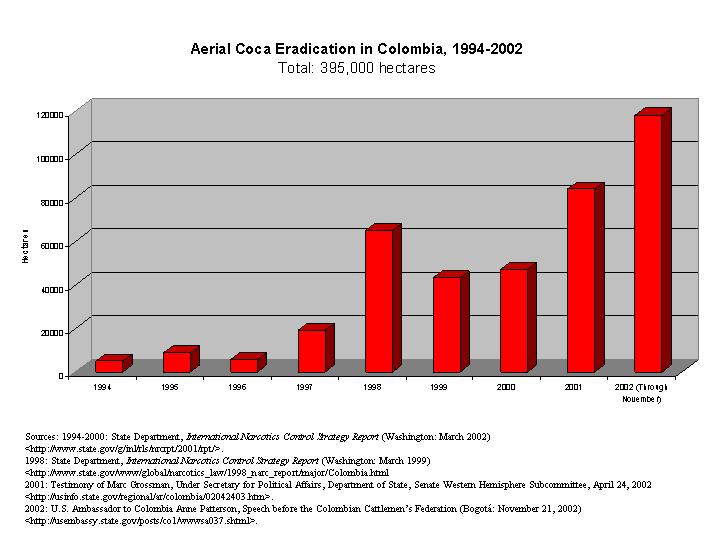

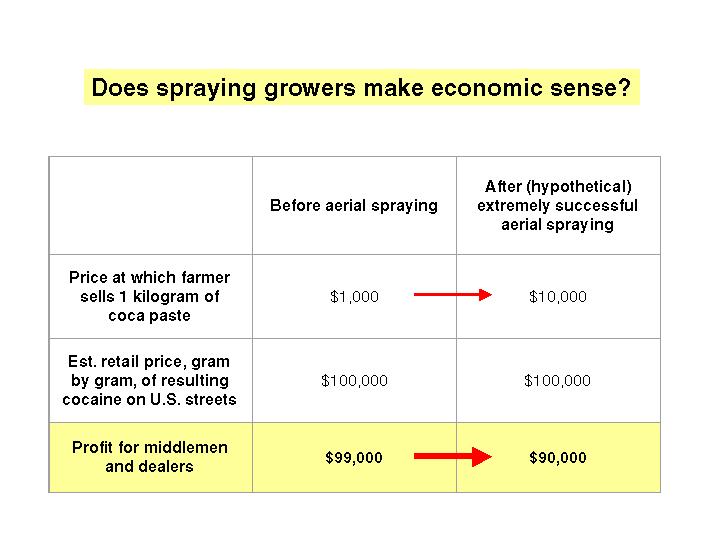

Isacson Let me begin by congratulating the committee for holding a hearing about the crisis of Colombian heroin. To my knowledge, this problem has never been given such a high profile here in Washington. We’ve already seen today that Colombia’s heroin crisis is severe, and getting worse. But it has also been made clear today that we’re still grasping for solutions to this problem. The question remains: what are we going to do about Colombian heroin? Not very long ago, the U.S. government thought it had the answer: a bit of alternative development combined with massive aerial spraying. The head of the State Department’s Narcotics Control Bureau, Rand Beers, told a Senate committee that “The alternative development program is being integrated with the aggressive opium poppy eradication program; and combined, the programs aim to eliminate the majority of Colombia's opium poppy crop within three years.” [1] That statement was made more than three years ago, in September of 1999. The poppy crop was not eliminated. In fact, the problem has grown more serious. Elusive poppy cultivation I want to caution the committee that simply increasing aerial spraying is not likely to reduce the poppy crop significantly. There are several reasons for this. First, opium poppy is an annual plant. It yields one harvest and dies whether it’s sprayed or not. Newly planted poppies will yield opium latex within 120 days. A spray program would have to be enormously nimble to catch up with that kind of growth cycle. Poppy cultivation is also hard to find. The crop is grown in isolated, high-altitude zones along the spine of the Andes, in rugged terrain with lots of cloud cover, in plots of usually not much more than an acre. Poppy is so elusive that since 1999, the State Department hasn’t even had a decent estimate of how much is being grown in Colombia. [2] There is no available estimate of acreage. Klaus Nyholm, who heads the UN Drug Control Program’s Bogotá office, said in July 2001, “we don’t have good images or even a good impression of how much poppy there is in Colombia … We believe there has been a rather strong increase … Estimates so far have ranged from between six to ten to twelve thousand hectares. I believe that it could easily be twelve or fifteen thousand, or even more, but we don’t know.” [3] To make things more complicated, a recent report from the Colombian government drug czar’s office alleges that poppy cultivation actually decreased by nearly a third between 1999 and 2001, from 6,500 to 4,200 hectares. [4] The upshot is, if we can’t even tell how much there is, how are we going to be able to eradicate it? But it gets worse. Let’s take Mr. Nyholm’s estimate of 15,000 hectares. That sounds like a lot of land. But in fact, if you were to put all those poppy crops together, they would fit into a square only 7.6 miles on a side. That’s smaller than the District of Columbia, but it’s scattered all around a country the size of Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma put together. (See Appendix A.) A country where two-thirds of the people earn less than two dollars per day and there is little law and order, so there are strong incentives for people to grow the stuff. I am not convinced that spray planes and helicopters alone can keep up with this. Lessons from coca spraying The United States’ experience trying to spray coca in Colombia is also instructive. Over the past seven years our coca spray program can only be described as massive. Since 1996, the U.S. and Colombian governments have sprayed herbicides over nearly a million acres of Colombian soil (just to kill coca; the poppy spraying has been in addition to this). (See Appendix B.) Yet we have seen coca cultivation in Colombia triple, from 57,000 hectares in 1996 to 169,000 hectares in 2001, while the total amount grown in South America has stayed about the same. (See Appendix C.) Colombia has thirty-two departments, or provinces. When large-scale coca spraying began in 1996, four of these departments – perhaps five – had more than a thousand hectares of coca. Spraying was able to reduce coca cultivation for a short amount of time in some specific zones. But at the end of last year, a survey carried out by the UN and the Colombian Police Anti-Narcotics Division found at least a thousand hectares in thirteen departments. [5] (See Appendix D.) Despite all of our spraying, coca is spreading like a stain on the map of Colombia. One reason that spraying has not worked against coca is simple economics. Spraying targets the part of the drug-production process where the drugs are easiest to find – the plants sitting in the ground. But this is not the part of the drug-production process where the money is. A Colombian peasant usually gets about $1,000 for a kilogram of coca paste. Narcotraffickers then turn the paste into cocaine and sell it on U.S. streets for $100 per gram or more. The cocaine coming from that kilo of paste has a retail value of at least $100,000, meaning that there is a $99,000 profit going to middlemen and dealers. Now suppose a very successful spraying program makes coca paste so hard to come by that the price jumps from $1,000 per kilo to $10,000. (This has never happened before.) The effect will be to reduce the profit for middlemen from $99,000 to $90,000. (See Appendix E.) The dynamic with heroin trafficking is the same. Spraying is simply not likely to hurt the drug trade. Policy alternatives What, then, do we do to start reducing drug production in Colombia? I wish there were a simple answer, but there is not. Instead, there is a very unsatisfying, complicated answer: we have to do many things at once, and we have to spend a lot of money, and only a fraction of this money should go to forcible eradication. In particular, we have to devote more attention and resources to three areas that aren’t getting enough of either: those are alternative development, ending impunity, and treating addicts. In much of rural Colombia, there is simply no way to make a legal living. Security, roads, credit, and access to markets are all missing. The most that many rural Colombians see from their government is the occasional military patrol or spray plane. When the spray planes come, they take away farmers’ illegal way of making a living, but they do not replace it with anything. That leaves the farmers with some bad choices. They can move to the cities and try to find a job, though official unemployment is already 20 percent. They can switch to legal crops on their own and risk paying more for inputs than they can get from the sale price. They can move deeper into the countryside and plant drug crops again. Or they can join the guerrillas or the paramilitaries, who will at least keep them fed. Spraying without providing development assistance not only doesn’t work, it probably strengthens the guerrillas. Remember that the classic U.S. doctrine of counterinsurgency insists that large amounts of development aid have to be transferred in order to help the government win the people’s “hearts and minds.” But when thousands of families get sprayed and then are not reached by development aid, their opposition to the government hardens. This is counterinsurgency in reverse, and it’s good news for the guerrillas. As of early this year, U.S. alternative development programs had reached about 1,740 poppy-growing families, covering about 1,070 hectares. [6] The programs have grown since then, but it still appears that the majority of families facing eradication are not being reached by development efforts. In Putumayo department, where the U.S. and Colombian governments sprayed 50,000 hectares of coca this fall, the idea of alternative development is being nearly abandoned; the State Department reported in March that “alternative development efforts … might be better concentrated in neighboring departments where viable economic activities already exist.” [7] It seems that the peasants of Putumayo are simply out of luck and must fend for themselves. Their desperation plays right into the hands of the FARC guerrillas, who have a strong presence in Putumayo. A major increase in alternative development has to be at the center of any strategy to reduce heroin production in Colombia. Alternative development should be easier to carry out in poppy-growing zones than in coca zones, for two reasons. First, the guerrillas and paramilitaries do not pose as much of a threat, because they are not as involved in the poppy trade. DEA Administrator Asa Hutchinson told the Senate International Narcotics Control Caucus in September, “Our indication is that the terrorist organizations are principally engaged in the cocaine trafficking. There are other criminal organizations in Colombia that are heavily engaged in heroin… [but] thus far, we're not seeing significant terrorist involvement in the heroin side.” [8] Most poppy-growing areas have more government presence and more infrastructure than coca-growing areas. The other reason it should be easier is that there is an obvious alternative crop: coffee, which grows best at the same altitudes as heroin poppy. The U.S. Congress has shown a desire to help our Latin American neighbors emerge from the crisis caused by the recent plunge in worldwide coffee prices. Last month, the House of Representatives passed a bipartisan resolution calling on the United States to “adopt a global strategy to respond to the coffee crisis with coordinated activities in Latin America, Africa, and Asia to address … short-term humanitarian needs and long-term rural development needs.” Alternative development in poppy-growing areas must be part of that strategy. In addition to alternative development, we must never forget that Colombia’s status quo, its crisis of drugs and violence, benefits some very powerful people who are getting away with their illegal activities. Only some of these people are guerrillas and paramilitaries. We need to go beyond spraying peasants and jailing addicts, the weakest links of the drug-trafficking chain. We have to devote more resources to stopping the traffickers who maintain international networks, the corrupt government officials who don’t enforce the laws, and the bankers who launder the money. Too many of them are getting away with it. Finally, we have to continue the past few years’ increases in funding for treatment of addicts here at home. Remember the 1994 Rand Corporation study that asked, “How much would the government have to spend to decrease cocaine consumption in the U.S. by 1%?” RAND found that a dollar spent on treatment is as effective as ten dollars spent on interdiction and twenty-three dollars spent on crop eradication. [9] We are all in agreement that the crisis of Colombian heroin has reached frightening proportions. The way out of the crisis, though, is going to be complicated, expensive and frustrating, just like the conflict in Colombia that helps to prolong the problem. I ask the committee not to place all of its eggs in the basket of spraying and aid to Colombia’s security forces. We are going to need a much fuller mix of strategies if we are going to solve this. Thank you very much. I look forward to your questions. [1] Statement of Rand Beers, Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, before the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, September 21, 1999 <http://www.ciponline.org/colombia/00092102.htm>. [2] United States, Department of State, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (Washington: March 2002) <http://www.state.gov/g/inl/rls/nrcrpt/2001/rpt/>. [3] United Nations, Office of Drug Control and Crime Prevention, Press Conference with Klaus Nyholm, representative for Colombia and Ecuador, Bogotá, July 24, 2001 <http://ciponline.org/colombia/072402.htm>. [4] Government of Colombia, Dirección Nacional de Estupefacientes, “Cultivos Ilícitos y el Programa de Erradicación,” (Bogotá: 2002) <http://www.dnecolombia.gov.co/contenido.php?sid=18>. [5] United Nations Drug Control Program, Colombian government National Narcotics Directorate, Colombian National Police Anti-Narcotics Division, “Localización de Areas con Cultivos de Coca, Proyecto SIMCI, Censo Noviembre 01 de 2001,” (Bogotá: SIMCI project, 2001) <http://ciponline.org/colombia/2002map.jpg>. [6] Department of State, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. [7] Ibid. [8] Transcript, Hearing of the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control on "U.S. Policy in the Andean Region," September 17, 2002 <http://drugcaucus.senate.gov/hearings_events.htm>. [9] C. Peter Rydell and Susan S. Everingham, “Controlling Cocaine: Supply Versus Demand Programs,” (Santa Monica: RAND, 1994). |

|

|

| Asia | | |

Colombia | | |

| |

Financial Flows | | |

National Security | | |

| Center

for International Policy |