|

| Home | | |

Analyses | | |

Aid | | |

| |

| |

News | | |

| |

| |

| |

| Last

Updated:5/19/00 |

| Sen.

Joseph Biden (D-Delaware), Report to the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign

Relations, May 3, 2000

May 3, 2000. The Honorable JESSE HELMS Chairman, Committee on Foreign Relations DEAR MR. CHAIRMAN: On April 19 and 20, I traveled to Colombia to examine counternarcotics programs there. In particular, my objective was to discuss the "Plan Colombia" proposed by the Colombian Government, and the U.S. proposal to assist the plan. While there, I met extensively with President Pastrana, Minister of Defense Ramirez, the President's Chief of Staff, Jaime Ruiz, U.S. Ambassador Curt Kamman, and senior Embassy officials. I also met with representatives of Colombian non-governmental organizations working on human rights, and representatives of the Colombian offices of two U.N. agencies. I owe a great debt of gratitude to the Colombian Government, particularly President Pastrana, for facilitating my visit. President Pastrana graciously hosted me at his government guest house in Cartagena. I also owe much to U.S. Ambassador Curt Kamman, Political Counselor Leslie Bassett (who served as the delegation control officer), and other staff of the Embassy who traveled with us to Cartagena. I was accompanied and assisted on the trip by Minority Counsel Brian McKeon, and Professional Staff Member Marcia Lee. They also traveled to Colombia in March for four days, during which they conducted numerous meetings and visited forward operating locations in southern Colombia. Some portions of this report are based on their work in March. The delegation was ably assisted throughout the trip by Lt. Cdr. Valerie Ulatowski, USN, to whom I am extremely grateful. I came away from my visit convinced that the U.S. Congress should act quickly to approve President Clinton's request for supplemental funding for Colombia. Unless the Congress acts quickly to approve funding for this plan, a critical opportunity in the fight against narcotics trafficking in Colombia may be lost. I understand the Committee on Appropriations will soon markup the Fiscal Year 2001 foreign operations appropriations bill, as well as the Colombia supplemental for Fiscal 2000. I hope this report will be useful to the Senate during consideration of this important issue. Sincerely, JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Ranking Minority Member. (III)

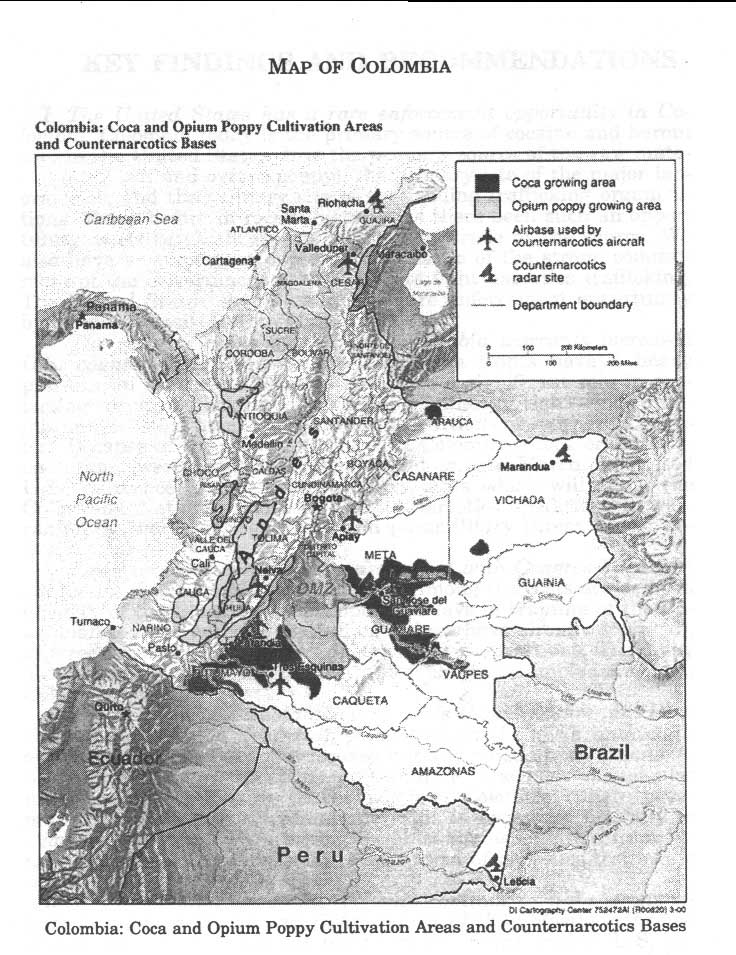

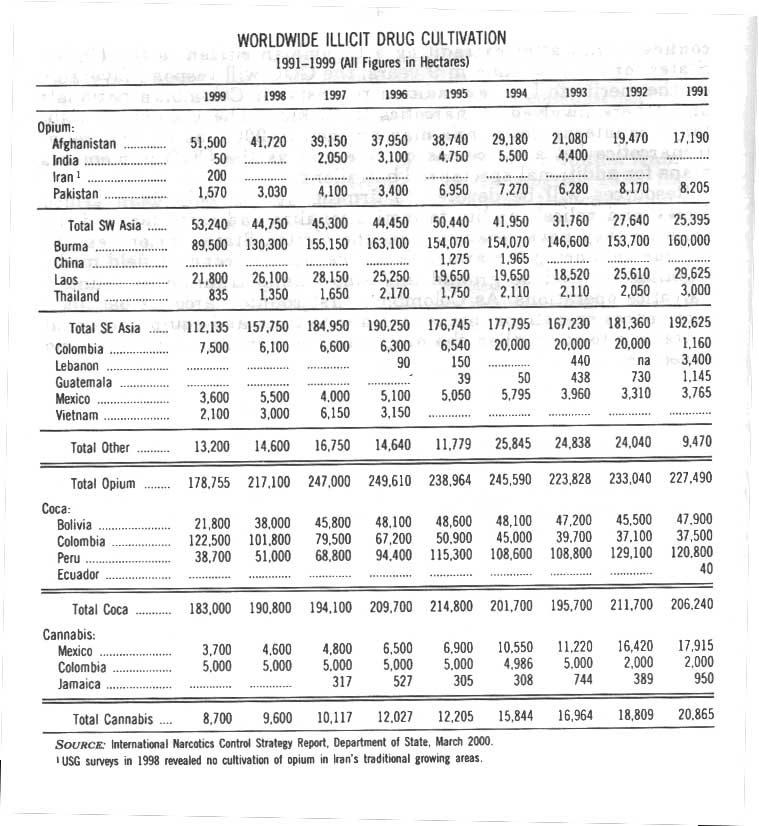

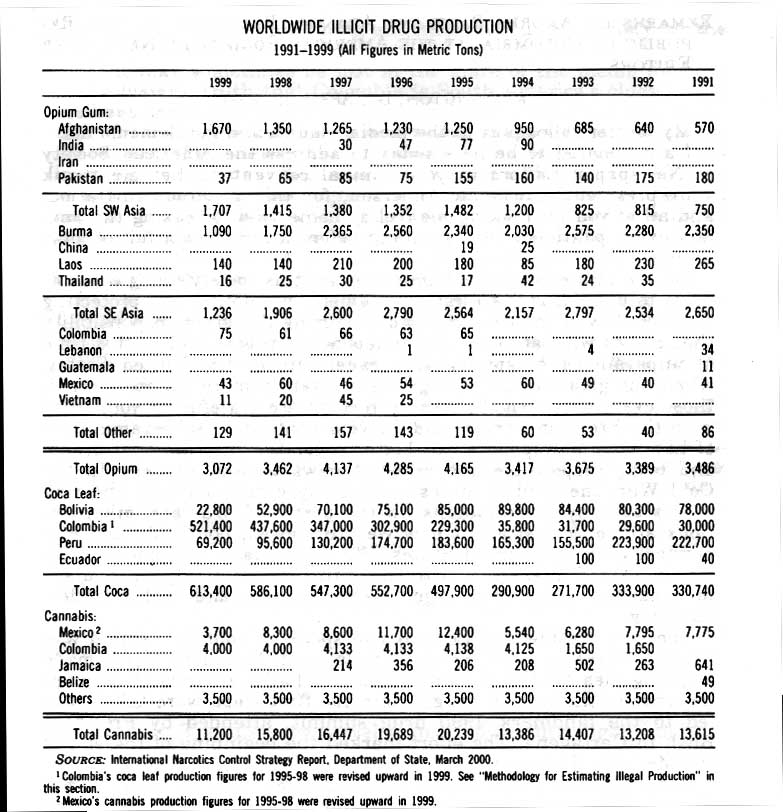

KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 1. The United States has a rare enforcement opportunity in Colombia. Colombia today is the primary source of cocaine and heroin sold in the United States. It is the primary source of the raw material (coca leaf and opium poppy), the primary site of the major laboratories, and the primary site of the leading trafficking organizations. Never before in recent history has there been such an opportunity to strike at all aspects of the drug trade at the source. We also have an important opportunity because of the strong commitment of the Government of Colombia to fight narcotics trafficking. The United States should seize this rare enforcement opportunity by providing assistance to Plan Colombia. 2. The security crisis in southern Colombia warrants increased U.S. counter-narcotics assistance. Guerrilla fronts have a heavy presence in southern Colombia and have a significant role in protecting drug trafficking operations. Similarly, right-wing paramilitary organizations are operating in portions of southern Colombia. Because of security concerns, U.S.-Colombian coca eradication operations were temporarily suspended in late March. Increased U.S. assistance to Colombian military units which will assist the Colombian National Police in counter-narcotics operations is warranted by the serious guerrilla and paramilitary threat to the Police. 3. There are considerable costs associated with Congress' delay in approving the Colombia supplemental. Among the costs are delayed delivery of the Blackhawk helicopters, delays in training of the Colombian counter-narcotics battalions (which have already occurred), and reduction in U.S.-Colombian eradication operations. The delay also undermines President Pastrana's ability to implement Plan Colombia. 4. The U.S. and Colombian Governments should ensure that Plan Colombia focuses on drug trafficking both in the north and south of Colombia. Plan Colombia focuses initially on southern Colombia, where guerrilla organizations predominate. The plan should also focus on coca trafficking in the north of Colombia, where paramilitary organizations predominate. This is necessary not only to demonstrate that no trafficking organization is immune from attack, but also to contain the further spread of narcotics trafficking in the north. 5. The Colombian Government should continue to make strong ef forts to improve the human rights record of the Colombian Armed Forces, and to prosecute all violations of human rights. U.S. engagement with Colombia is an important factor in continued improvement of the human rights situation in Colombia. President Pastrana reiterated his personal commitment, and that of the Colombian Government, to improving human rights. Congress should consider increasing the amount of U.S. assistance proposed for human rights efforts. 6. Coordination between the Army and the Police needs improvement. Important to the success of the military component of Plan Colombia will be coordination between the Colombian Army and the Colombian National Police. There are indications that the Police are unreceptive to working closely with the Army. Similarly, the Army counter-narcotics battalion at Tres Esquinas has conducted operations unilaterally-without including the police in planning or giving them adequate notice to participate. The United States must continually emphasize to the Colombian Government the importance of improving Army-CNP cooperation. 7. The United States is well-served by the Country Team, but more staff are needed. The U.S. Embassy team working on Plan Colombia is led by a veteran Ambassador, is highly motivated and is working diligently to advance U.S. counter-narcotics objectives. Morale appears to be high. But the Narcotics Affairs Section is understaffed and needs additional personnel, and the Political Section needs additional officers to monitor human rights. OVERVIEW: AID TO "PLAN COLOMBIA" IS A CRITICAL OPPORTUNITY FOR THE UNITED STATES Since February, a request by President Clinton to provide nearly $1 billion in supplemental funding in Fiscal 2000 to help Colombia and its neighbors fight drug trafficking has been pending in Congress. The request was approved by the House of Representatives in March, but it has since languished in the Senate. During the Easter recess, I traveled to Colombia for a first-hand look at the situation and to discuss U.S. and Colombian counternarcotics programs with senior Colombian Government officials, U.S. Embassy officials, and representatives of non-governmental and international organizations. I spent several hours over the course of two days with President Pastrana, who graciously hosted me at the presidential guest house in Cartagena. I believe that my lengthy meetings with him, mostly in informal settings, afforded me the opportunity to take the full measure of the man. I am fully convinced of President Pastrana's personal commitment to the counter-narcotics effort. I also spent several hours with U.S. Ambassador Curt Kamman and his team, both in Bogota and in Cartagena. I was deeply impressed by the dedication, knowledge and commitment of the senior Embassy team. I came away from my visit convinced that the U.S. Congress should act quickly to approve President Clinton's request for supplemental funding for Colombia. Unless the Congress acts quickly to approve funding for this plan, a critical opportunity in the fight against narcotics trafficking in Colombia may be lost. Colombia today is the primary source for two leading narcotics sold on the streets of the United States: cocaine and heroin. It is the primary source for the raw materials (coca leaf and opium poppy), the site of the major processing labs, and the site of the major trafficking organizations. Never before in recent history has there been such an opportunity for the international community to strike against the bulk of the narcotics industry at the source. Colombia today has a president committed to working closely with the United States. He has developed a $7.5 billion dollar plan - "Plan Colombia" - to fight traffickers and revive his country's economy. President Clinton has proposed that the United States provide $1.6 billion to assist Colombia and other Andean nations, or about 20 percent of the plan. International financial institutions have provided nearly $1 billion. Europe and Japan are being asked to contribute as well. Every day that the Senate delays imposes a cost on this plan and to U.S.-Colombian counter-narcotics efforts. Production of the proposed helicopters will be delayed, as will training of the necessary pilots. Training of two Colombian counter-narcotics battalions has already been delayed. The Colombian effort to raise money from Europe is proceeding slowly in part because of hesitation in Washington. Most important, delay in Washington undermines President Pastrana and his ability to implement the plan in Colombia. Helping Colombia is squarely in America's national interest. It is the source of many of the drugs poisoning our people. It is not some far-off land with which the United States shares little in common. It is an established democracy in America's backyard-just a few hours by air from Miami. Colombia is hardly a stranger to the drug war. It has been battling this scourge for decades. In the 1980s, its equivalent of the Supreme Court was attacked by traffickers. A decade ago, its presidential candidates were gunned down. The current president, when a candidate for Mayor of Bogotá, was kidnapped by traffickers. The people of Colombia have demonstrated great courage in fighting drug trafficking. Colombia has achieved some major successes in this effort-in the 1990s it dismantled the major cartels in Medellín and Cali-cartels that a decade ago were thought to be invincible. Last October, in a joint U.S.-Colombian operation, over 30 major traffickers were arrested on the same day. America's apparently insatiable demand for narcotics has, undeniably, helped fuel the drug trade in Colombia. Colombia seeks significant U.S. assistance to help confront this trade-and is pledging substantial funds and action by its government. Colombia has a highly professional police force dedicated to counter-narcotics, and now requests U.S. assistance to train and professionalize military units that will be used against narcotics traffickers. I believe the United States should answer Colombia's call for help. There is, to be sure, no guarantee that this plan will work in significantly reducing narcotics trafficking. Anybody who says they are certain that it will succeed is either lying or is a fool. But in my 28 years in the Senate, I have been deeply involved in studying and debating narcotics policy. I strongly believe that at this moment, with this president in Bogotá, we have a real opportunity to make a significant difference against the drug trade in Colombia. That opportunity could slip away unless we seize this rare enforcement moment. BACKGROUND ON COLOMBIA AND PLAN COLOMBIA A. OVERVIEW OF THE SITUATION IN COLOMBIA Colombia is the third most populous country in Latin America, with just under 40 million people. It is the second oldest democracy in the Western Hemisphere, after the United States. Unlike many countries in Latin America, it has rarely been subject to military dictatorship. Military rulers have governed Colombia for only three brief periods since the formation of the republic in the early 19th century the last time was over forty years ago. Today, as democracies across the Andes are threatened by renewed rumblings from military barracks, or authoritarian tendencies by incumbent leaders, Colombia remains squarely and unalterably in the camp of democratic nations. Although civilian rule has been the norm, it has not spared Colombia from instability. Rather, Colombian history has long been marked by internal conflict. During the late 1940s and 1950s, for example, Colombia went through a civil conflict referred to as "La Violencia," during which over 200,000 people were killed. The violence ended when the two major parties, the Liberals and Conservatives, agreed on a 16-year period of "National Front" government during which the two parties rotated the presidency and had parity in other elected offices. It might be said that Colombia is going through a second-or perhaps extension of-"La Violencia". Colombia today is wracked by violence. It faces a three-front war: with drug traffickers, with left-wing guerrillas, and with right-wing paramilitaries. These fronts are often intertwined; for example, guerrillas and paramilitaries both cooperate with drug traffickers, and the paramilitaries cooperate with the armed forces. None of these groups are monoliths; there are numerous drug trafficking organizations, two guerrilla groups, and numerous right-wing paramilitary groups. The Colombian Government actively fights on two of these fronts: against the drug traffickers and the guerrillas, and occasionally fights, but occasionally cooperates with, the right-wing paramilitaries. At the same time, the government is engaged in peace negotiations with both guerrilla groups, and has agreed to "demilitarized zones" for both of them. The violence associated with the civil conflict and drug trafficking has been accompanied by an erosion of the rule of law. Last year, for example, there were some 25,000 murders in Colombia (this far exceeds the murder rate in the United States-a country with more than six times the population of Colombia-where there were about 17,000 murders in 1998). Of these, about 2,000-3,000 were considered to be "political" crimes, that is, crimes related to the civil conflict. The rest were common criminal murders. Kidnaping is also widespread: there were over 2,500 last year, which is one out of every three kidnapings in the world. Justice is often denied. A recent judicial report in Colombia found that 63 percent of crimes go unreported, and that 40 percent of all reported crimes go unpunished. Because of the violence, particularly the risk of kidnaping, the State Department currently warns U.S. citizens against traveling to Colombia, and states that "there is a greater risk of being kidnaped in Colombia than in any other country in the world." Colombia is, as it has long been, the source of up to 75 percent of the world's processed cocaine (cocaine HCL). It now also holds the dubious distinction of being the world's leading producer of cocaine base (the intermediate step prior to cocaine HCL), as reductions in cultivation in Bolivia and Peru have pushed cultivation into Colombia. Colombia is also the leading supplier of heroin to the United States. Colombia is currently suffering through a recession. Its gross domestic product fell by 3.5 percent in 1999, the first time the Colombian economy suffered negative growth in three decades. Unemployment at the end of 1999 was around 20 percent; inflation was over 9 percent. And approximately one million people (out of a total population of about 40 million) have been internally displaced in the last several years because of the civil conflict. B. U.S.-COLOMBIAN RELATIONS AND THE BACKGROUND TO PLAN COLOMBIA U.S.-Colombian relations have historically been strong. Under the previous Colombian president, however, the relationship soured because of credible allegations that he received financial contributions for his 1994 presidential campaign from drug traffickers. This led President Clinton to twice "decertify" Colombia under the Foreign Assistance Act. A general reduction in the level of cooperation between the United States and Colombia also resulted. The inauguration of President Andrés Pastrana in August 1998 changed the atmosphere in the U.S.-Colombian relationship. President Pastrana made restoration of strong relations with the United States a high priority, and he has succeeded in that objective. Undoubtedly, President Pastrana has demonstrated his commitment to a key issue for the United States-the fight against narcotics trafficking. Among other things, Pastrana has released a first-ever national drug strategy, and renewed extradition of criminals to the United States, as authorized by a December 1997 constitutional amendment. He has also formulated a plan to combat drug trafficking and revive the economy, which he has called "Plan Colombia". Announced in September 1999, the plan calls for a $7.5 billion investment over three years (2000-2002); of this, the Colombian Government would provide $4 billion, and would seek the remaining $3.5 billion from the international community. As articulated by the Colombian Government, Plan Colombia focuses on five areas: 1. The peace process (i.e., negotiations with the guerrillas); 2. The economy; 3. The counter-drug strategy; 4. Reform of the justice system and protection of human rights; 5. Democratization and social development. In January 2000, President Clinton announced his proposal for U.S. support of Plan Colombia: a two year, $1.6 billion contribution. Of this amount, approximately $150 million is the base Colombia program for Fiscal 2000 and 2001. The enhanced funding would include $954 million in supplemental appropriations in Fiscal 2000, and an additional $318 million in Fiscal 2001. The supplemental request was approved by the House of Representatives on March 30, and is currently pending before the Senate. NARCOTICS ISSUES A. BACKGROUND ON THE CURRENT NARCOTICS SITUATION 1. Trafficking Organizations Organizationally, the drug trade in Colombia is no longer dominated by major cartels based in Medellín and Cali, as it was a decade ago. Because of law enforcement pressure by the U.S. and Colombian Governments in the early and mid-1990s, these cartels have been largely dismantled, and their leaders killed or imprisoned. The result as been what the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) aptly terms the "decentralization" of the trade, with numerous smaller trafficking organizations emerging, the rise of independent traffickers in Bolivia and Peru producing their own cocaine HCL, and changes in the distribution networks such that Mexican organizations are not merely middlemen for the Colombians, they now have their own distribution networks in the United States. 2. Production and cultivation The organizational changes described above have not affected Colombia's role as the source of the large majority of processed cocaine, or cocaine HCL (up to 75 percent of the world's cocaine HCL comes from Colombia). Because of enforcement pressure in Bolivia and Peru, much cultivation has shifted to Colombia. As recently as 1995, Colombia only produced about 25 percent of the world's cocaine base; it is now the world's leading producer, at about 68 percent. Coca cultivation is literally exploding in Colombia: in the last four years, net coca cultivation has more than doubled in terms of area, from 51,000 hectares in 1995 to 122,500 hectares in 1999. Moreover, a recent U.S. intelligence study determined that Colombian leaf produced a higher yield than previously thought, and that Colombian labs were more efficient than previously thought. Colombia's estimated potential cocaine production in 1999 was 520 metric tons; this compares to 70 metric tons in Bolivia, and 175 metric tons in Peru. Much of this new cultivation is in southern Colombia, primarily in two departments (or provinces), Putumayo and Caquetá. The government does not have much of an institutional presence in this region-that is, there are few roads, schools, or hospitals-and has not for most of the history of the republic. It is remote and much of it is jungle. There is also significant cultivation in two northern departments, Norte de Santander and Bolivar. Nearly half of the coca in the country-about 56,000 hectares- is cultivated in Putumayo Department. Although I did not visit southern Colombia, in March two members of the Committee staff visited three forward Army and Police bases in Putumayo and Caquetá Departments, and rode on Colombian National Police helicopters to witness an eradication operation (i.e., fumigation of coca leaves) in Caquetá. They also flew by plane over portions of Putumayo Department where significant cultivation occurs. In Caquetá much of the cultivation the staff saw was somewhat hidden, at least on the ground, within wooded areas. That is, the peasants clear-cut several acres of jungle to grow a plot of coca, but attempted to keep the presence of the field hidden on the ground (though it obviously cannot be hidden from aerial view). In Putumayo, there was no such effort to hide the plots of coca: it was out in the open, and went on and on for hundreds of acres. In addition to coca cultivation, Colombia is now the leading source of heroin sold in the United States. Starting from almost nothing a decade ago, the opium and heroin trade has expanded significantly: by 1993, Colombian heroin accounted for 15 percent of the U.S. supply, and by 1998 it accounted for 65 percent. In 1999, Colombia produced an estimated 8 metric tons of heroin, more than Mexico. Though it amounts to only a small percentage of the world's heroin supply, Colombian heroin dominates the trade in New York and other East Coast cities; it is high quality and of high purity, allowing it to be smoked rather than injected. 3. Involvement of guerrillas and paramilitaries in narcotics trafficking In addition to the drug trafficking organizations, both left-wing guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries are involved in the Colombian drug trade. The two major guerrilla groups in Colombia are the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (commonly referred to by its Spanish-language acronym of "FARC"), and the National Liberation Army (or ELN). The FARC is the larger of the two-it is believed to have about 10,000-14,000 personnel, and is better trained and equipped. It operates primarily in the south and eastern lowlands, though it has some urban cells. The ELN has about 3,0006,000 personnel and operates primarily in the north and the center of the country. It would be "misleading," says an unclassified portion of an otherwise classified DEA report, to characterize the FARC or ELN as drug cartels per se. Rather, they assist traffickers by providing security for drug operations and assisting in transportation of narcotics. They also impose taxes, not only on the drug trade but all economic activity in areas they control. In some areas, they allegedly establish the price paid to peasants for coca leaf. Estimates of the profits the guerrillas derive from this activity vary significantly, from a few hundred million dollars to nearly $2 billion per year (this higher end estimate was provided by a Colombian Army official, and it appears to be greatly inflated). Right-wing paramilitary groups are also involved in the drug trade, and some of them are considered to be traffickers. The paramilitaries were originally formed in the 1980s as a response to guerrilla violence, and several of these were originally authorized by the government to protect rural areas. These groups are now illegal. The leader of the largest umbrella group of paramilitaries is Carlos Castaño, the leader of the "Peasant Self-Defense Groups of Cordoba and Uraba (ACCU)." Most paramilitary operations are in the north, though they do have a presence in the south. Like the guerrillas, most of the paramilitary groups do not appear to be directly involved in any significant drug cultivation, but instead levy taxes and protect the traffickers. The DEA recently testified, however, that Castaño's organization, and possibly other paramilitary groups, "appear to be directly involved in processing cocaine," and that "at least one of these paramilitary groups appears to be involved in exporting cocaine from Colombia." B. KEY ISSUES IN IMPLEMENTATION OF PLAN COLOMBIA During my visit, I focused on several key issues related to the implementation of Plan Colombia by the Colombian Government and the U.S. Government. 1. The military component of U.S. assistance for Plan Colombia - and the need for it A key component of the U.S. contribution to Plan Colombia is military assistance, specifically, the training and equipping of three Colombian Army counter-narcotics battalions. One battalion of about 950 men was trained last year by U.S. forces, and is now in p lace at the Tres Esquinas base in southern Caquetá Department. Together the three battalions will form a brigade, just under 3,000 strong. The basic argument for training and equipping the Colombian Army-rather than the Colombian National Police (CNP), the primary counter-narcotics agency in Colombia-is that the CNP lacks the muscle to take on the guerrillas and paramilitaries that are involved in drug trafficking in southern Colombia. In other words, because the guerrillas and paramilitaries often protect traffickers and their operations, the police cannot go after the traffickers without also risking encounters with well-armed irregular forces. And, because the police are primarily a law enforcement agency, it lacks the military power and training to confront the well-trained and well-equipped FARC fronts and paramilitary units. It bears emphasis that the United States is hardly neglecting the CNP with this plan. It has provided over $775 million in support for the CNP since the mid-1980s, and the Administration proposal provides roughly $100 million in additional equipment and training for the CNP. The security threat in Colombia warrants increased U.S. counternarcotics assistance. Numerous FARC fronts (the estimate of how many is classified), as well as paramilitary units operate in the south. Nearly half of the coca leaf grown in Colombia is located in Putumayo Department. There is a continuous security threat to the current U.S.-Colombian eradication operations. In March, the State Department temporarily suspended day-time coca spraying operations because of the security situation. During the past four years (including the first three months of this year), U.S.-CNP spray planes in Colombia were hit over 100 times by groundfire, including 21 times in the last six months alone. Because of the threat from groundflre, two helicopter gunships and a search and rescue helicopter continually accompany the spray planes. U.S. assistance to the battalions will be in two basic forms: training by U.S. military forces, and equipment, particularly helicopters. Most of the training will be conducted in Colombia by U.S. Special Forces on temporary duty. Some of the training, particularly for the brigade headquarters staff, will be conducted in the United States. Anywhere from 20 to 160 U.S. personnel will be involved in training at any one time. Some training missions will be conducted at forward operating bases in Colombia. The training will be just that: training. Pursuant to a Department of Defense memorandum issued by Secretary of Defense Cohen in October 1998, Defense Department personnel are prohibited from accompanying foreign law enforcement and military forces on actual counterdrug field operations or "participating in any activity in which counterdrug-related hostilities are imminent." Moreover, they are prohibited by the same directive from accompanying such law enforcement forces outside a secure base or area. Secretary Cohen reemphasized these points in a memorandum to Joint Chiefs Chairman Shelton in March 2000. In addition to training the battalions, the United States will fill a key shortfall in the Colombian military arsenal: tactical mobility. Under the U.S. contribution to the Plan, the United States will provide 30 UH-60 helicopters (Blackhawks) to the Colombian Army. The Blackhawks will be newly procured from the contractor, Sikorsky Helicopters. Delivery of the helicopters will be at a rate of two per month, and is projected to begin in early 2001. In the interim, 15 additional UH-lNs (Hueys) will be provided to Colombia, which will add to the 18 already in country. Up to six of these Hueys, however, will likely be diverted from Colombian counter-narcotics operations for use in training additional Colombian pilots. 2. The costs of delaying the supplemental There are considerable costs associated with Congress delaying the supplemental appropriations that would provide nearly $1 billion in assistance for Colombia in Fiscal 2000. First, delay exacerbates the lag time for procurement of the Blackhawks, the training of the pilots and the building of the infrastructure to house and maintain them. Even if the supplemental were enacted today, the first Blackhawks could not be delivered until next year due to production schedules. Second, the training for the second and third counter-narcotics battalions has been delayed because of uncertainties about the funding for Colombia. Training of the second battalion was scheduled to begin in early April. Because the entire training schedule was due to occur in sequence-that is, training of the second battalion followed by training of the third-the entire training schedule will now likely be pushed back. Third, because of the delay in the supplemental, the Huey helicopters that are currently in Colombia and designated for the counter-narcotics battalions are not yet forward deployed-for the simple reason that funds are not available, because they were to be provided by the United States under the supplemental. Consequently, the initial counter-narcotics battalion at Tres Esquinas is greatly hampered in its range of operation. To date, it has conducted operations only on foot. Fourth, the State Department has forward-funded some eradication operations in Colombia because it expected the supplemental to pass by now. The Department increased the operating tempo of eradication, in effect gambling that the money from Congress would soon arrive. It was a reasonable gamble given the original 64-135 00-2 10 11 reception to President Clinton's proposal and the recent successes in eradication. But the gamble has not worked. The State Department just laid off 40 contract employees, severely reducing spraying operations in Guaviare Department, where there has been significant success in spraying in recent years. Fifth, the delay in approving the supplemental undermines Colombia's efforts to raise funds from Europe and Japan. In April, President Pastrana met with British Prime Minister Tony Blair, and in March his foreign minister traveled to Tokyo to seek help from Japan. This summer, Spain will host a conference of donor countries to garner more international support. But, in the face of inaction on our part, all those efforts may be a waste of time. I do not expect Europe and Japan to contribute to Plan Colombia unless the U.S. Congress takes the first step. Finally, and most important, we need to move now because we have a limited window. President Pastrana is an ally of the United States. But he is only going to be president for two and one-half more years. The hesitation of the United States has a negative psychological effect in Colombia and Pastrana's effort to push forward his strategy. Every day we wait to pass the spending bill means one less day that Pastrana will have to implement Plan Colombia. And every day that we delay, more coca seeds are planted, more coca leaf is processed, and more cocaine is shipped to this country. 3. What does the Plan do to counter trafficking by paramilitaries? The debate in the U.S. Congress to date has focused in part on suggestions that the "push into southern Colombia" may be a counter-insurgency in disguise-in that the south is also the area where the stronger of the two guerrilla groups, the FARC, predominates. During my visit to Colombia, I impressed upon Colombian and U.S. Embassy officials about the importance of taking actions against paramilitary trafficking in the north of the country simultaneously with the push into the south-not only to demonstrate that no trafficking organization is immune from attack, but also to contain the further spread of narcotics trafficking in the north. The push into southern Colombian will in fact engage paramilitaries. Although it is not well known in this country, hundreds of paramilitaries are struggling with the FARC for control of the drug trade in Putumayo province. Operations against drug trafficking in Putumayo will not be targeted against organizations because of their political views, they will be targeted against drug traffickers. In addition, the plan contemplates operations against drug trafficking elsewhere in the country during the second phase, beginning during the second year. Finally, senior Embassy personnel indicated that it was an achievable objective to undertake operations against coca cultivation in the north of the country-where paramilitary organization predominate-simultaneous with the "push into southern Colombia." 4. Concerns about coordination between the CNP and the Armed Forces The military assistance component of Plan Colombia is predicated on the need for the Colombian Army to secure portions of southern Colombia so that police operations, and ultimately alternative development programs, can occur. The Colombian Army counter-narcotics battalions will not operate alone, because, as is the case with the U.S. military, there are legal restrictions on its ability to conduct law enforcement operations. Rather, they must coordinate their operations with the CNP, which has the law enforcement authority and expertise to make arrests and take down laboratories. The CNP is formally part of the Ministry of National Defense, but, as with any military establishment, there are institutional rivalries between the CNP and the other services. The rivalry between the CNP and the Army goes back at least half a century, when the two services backed different political parties during "La Violencia." The U.S. Government recognizes the importance of improving the joint efforts of the two services. During an appearance before the Committee on Foreign Relations on February 25, Brian Sheridan, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict, testified that the Colombian military needs to "better coordinate operations between the services and with the CNP." There are indications that the police are unreceptive to working closely with the Army. Similarly, the Army counter-narcotics battalion based at Tres Esquinas has undertaken several operations on foot unilaterally. These were not mere training missions: there was a counter-narcotics objective to each operation (typically a cocaine laboratory). The Army has failed to properly coordinate these operations in advance with the CNP, but instead gave the police only a few hours' notice that the operation was imminent-leaving the CNP inadequate time to prepare for the mission. Coordination between the two services will be essential to the success of the "push into southern Colombia." The United States must make it a high priority to foster and encourage coordination between the two services. Embassy officials are aware of this objective, and appear to be taking steps to promote it. So, too, are Colombian Government officials. I spoke at length about this issue with the President and the Minister of Defense, and impressed upon them the urgent need to improve coordination. The message should be constantly emphasized by the United States. 5. Security at forward operating bases In March, the Committee staff took a day-long trip to southern Colombia, namely Caquetá and Putumayo Departments. They visited the Larandia base in northwest Caquetá, the Army base at Tres Esquinas (on the Caquetá-Putumayo border in the western portion of Caquetá), and the CNP base at Villa Garzon in Putumayo Department. Because of time constraints and the Easter holiday period, I was unable to visit southern Colombia. I did, however, discuss the security issue with the U.S. Ambassador and the head of the U.S. Military Group at the Embassy. I impressed upon them the need to do everything possible to strengthen security at the forward bases. The key question for the United States is whether there is adequate security at the bases where U.S. trainers will be located during the training of the Colombian counter-narcotics battalions. It is currently anticipated that some training of the counter-narcotics battalions will be held at Larandia and Tres Esquinas, which are in southern Colombia in areas where FARC fronts operate. There is no such thing as perfect security, and it is unlikely that Colombian bases will ever meet standards of U.S. military bases. But U.S. forces should not be exposed to undue risk. Assistant Secretary of Defense Brian Sheridan stated in response to a question for the record after a February 2000 hearing of the Committee on Foreign Relations that "force protection measures in place are adequate for the deployment of U.S. personnel to train Colombian forces who conduct counterdrug operations." U.S. personnel in Colombia echoed this view, though they underscored that they are continually working with the Colombian military to improve security. 6. Selection and operation of the Blackhawks One question before Congress is whether the tactical mobility requirement of the Colombian Army can be adequately met with a cheaper option than the Blackhawks, namely Hueys. The option was rejected by the Administration for three reasons: the Blackhawk has a greater range, speed, and can carry more troops than the Huey. The following table demonstrates the differences: UH-60 UH-1N (Blackhawk) (Huey) To be sure, the costs of the Blackhawks are substantial: the initial investment under the supplemental is $385 million to fund the procurement, operations and maintenance, and pilot training. There will be associated costs for infrastructure at Colombian bases: at least $13 million in Fiscal Years 2000 and 2001. But the payoff is a far more capable helicopter to provide the critical requirement of the Colombian Army. The advantage of buying a new helicopter- as opposed to a upgraded, but decades-old helicopter-should be self-evident. Questions have been raised whether the Colombian military can adequately manage sophisticated helicopters such as the Blackhawk. The Colombian Army and Air Force, collectively, al- ready possess 20 Blackhawk helicopters. The Air Force helicopters are operational 80 percent of time, the Army helicopters 50 percent. The latter is skewed by the inclusion in the calculations of one Blackhawk with 73 bullet holes that has been inoperational for 18 months. If this single helicopter is not included in the data, the operational rate is 70 percent. These data compare favorably to the current CNP aircraft inventory, which is operational at a 65 percent rate. Perhaps more important, the operational rate of the Colombian military is comparable to the U.S. military, in which the operational rates of the Blackhawk average around 80 percent. So this data suggest that the Colombian Armed Forces have adequately learned how to operate and maintain the Blackhawks in their inventory, though additional pilots, maintenance crews, and infrastructure will be needed for the new helicopters. 7. Alternative development and assistance for the internally displaced Two important components of Plan Colombia are providing alternative development opportunities to peasants now growing coca and poppy, and assisting those that are internally displaced by the Plan and Colombia's conflicts. The U.S. portion of plan provides for $115 million for alternative development efforts in Colombia. This is clearly insufficient given the substantial need to persuade thousands of small farmers to switch from illegal activities. Colombia needs more; it is planning to contribute several hundred million dollars of its own funds, and is seeking funds for the effort from Europe-which has been asked to provide up to $1 billion for alternative development-as well as Japan. The key issue is one of timing: coordinating alternative development programs with enforcement measures, so the peasants have real economic alternatives at the moment their livelihood (albeit illicit) is being reduced. This has historically been a difficult challenge in the Andean region, because development programs often take longer to develop than enforcement programs. An added difficulty is that the Colombian Government agency responsible for alternative development, known as "PLANTE", is relatively new and is relatively small. Similarly, the Agency for International Development mission must build its capacity, as its program in Colombia in recent years has been negligible. The United Nations Drug Control Program (UNDCP), which has been operating in Colombia since 1985, has extensive experience in the Andes, and should be utilized in this effort. The Colombian Government plans to begin alternative development programs in Putumayo Department on a pilot basis (there are already programs underway in opium growing areas). Initial programs will be conducted, in coordination with eradication operations, in an area along the main highway south of the provincial capital. Unlike many areas in the rest of the province, the soil there is suitable for agriculture. The programs there will be an important test of whether real alternatives can work in that region. It should be recognized that even the best alternative development programs cannot work unless the area is secure. Put another way, we cannot expect the Agency for International Development and PLANTE to work in areas effectively controlled by guerrillas or paramilitaries. Plan Colombia also provides for assistance to the internally displaced. The battle between Colombia's armed actors-the military, the guerillas, and the paramilitaries-has had a tremendous impact on the Colombian people. Kidnapings, massacres, battles, and threats force tens of thousands of Colombian families to flee their homes each year and move elsewhere in the country. Squatter settlements of displaced people have sprung up around Bogotá and other cities. These internally displaced persons need food, clothing, shelter (temporary and permanent), health care, counseling, job training and employment. (In international law, these are not "refugees"; refugees must cross an international border. Those displaced by crises, but still within their own borders, are referred to as "internally displaced persons," or "IDPs"). Estimates of the number of IDPs vary considerably: ranging from several hundred thousand to 2 million. The State Department estimates that at least 800,000 people, primarily women and children, have been displaced since 1996-a level similar to those displaced in Kosovo in 1999. The "Red de Solidaridad Social" (RSS), Colombia's government agency which coordinates relief services, numbers the displaced at 400,000. The reason for the disparity turns on definitional disputes regarding precisely who is displaced. I am not in a position to settle this dispute, but it is clear that the government has a serious problem on its hands. The problem is widespread in the country. According to the Colombian Government, the internal displacement problem involves 139 of the country's 180 municipalities. Forty-four percent of IDP families are headed by a female, 23 percent of IDPs are less than seven years old, and nearly 17 percent are ethnic minorities. Most are poor families from rural areas with an agricultural background. The cause of displacement varies. The Council for Human Rights and the Displaced, a respected non-governmental organization in Colombia, estimates that 45 percent of IDPs are displaced by the paramilitaries; 30-32 percent by the guerrillas; and 8 percent by the armed forces. The push into southern Colombia is expected to displace 30,000 to 40,000 of the estimated 300,000 residents of the Putumayo Department. Many of those expected to be displaced are migrant farmers who have moved to the region to grow or pick coca. Because the displacements in Putumayo will be the result of U.S.-assisted enforcement measures under Plan Colombia, the United States will have a special responsibility to assist those displaced from that region. The Clinton Administration proposal requests $12 million in 2000 and $19 million in 2001 for resettlement assistance. Given the large number of people already displaced and the additional people who will be displaced as a result of the "push into southern Colombia," this amount is probably insufficient, and additional resources should be considered during debate on the supplemental or in the regular FY 2001 budget. 8. Embassy staffing requirements for Plan Colombia The Narcotics Affairs Section (NAS) in the U.S. Embassy is understaffed. In September 1999, with the approval of the Ambassador, the Section applied to Washington for 31 new positions to help manage the counter-narcotics program, which has grown significantly in the past few years-from about $20 million in Fiscal 1996 to some $235 million in Fiscal 1999-without a corresponding increase in staff to manage the program. Senior State Department officials have assured the Committee that these positions will be approved; to date, 18 of them have been. These staff are needed now. It bears emphasis that these additional 30 positions were requested before submittal of Plan Colombia. The Section estimates that it may need up to 20 additional positions in order to support the increase of U.S. assistance under Plan Colombia. The importance of the State Department providing adequate staffing to this mission cannot be overemphasized. If the U.S. Government is going to devote substantial resources to fighting narcotics in Colombia, it must provide adequate staff to help ensure that these resources are spent properly. C. COLOMBIAN GOVERNMENT AND PLAN COLOMBIA 1. Securing assistance from other international sources Plan Colombia is predicated on international assistance. The United States has pledged, but not yet provided, over $1 billion in new assistance. International financial institutions have committed nearly $1 billion. The Colombian Government is making serious efforts to raise additional funds from Europe and Japan. A donors conference, sponsored by Spain, will be convened in Madrid in July for this purpose. The Colombian government is working hard to solicit other international assistance. The week before my visit, President Pastrana traveled to the United Kingdom for meetings with Prime Minister Blair and Foreign Secretary Cook. In March, Colombian Foreign Minister Fernandez traveled to Tokyo to discuss a possible Japanese contribution. Should they be provided, contributions from other international donors are designed to complement the Colombian and U.S. portions of Plan Colombia. Europe is being asked to provide up to $1 billion for alternative development. The Japanese Government has expressed an interest in helping with reforestation and programs for the internally displaced. There are reasons to be skeptical that European states will provide assistance-Europe has been slow to provide assistance for Kosovo reconstruction-but one thing seems clear: neither Europe nor Japan is likely to provide assistance unless the United States does. In short, the failure of the United States to approve the supplemental has delayed commitments by other foreign donors. 2. Peace process Another key component of Plan Colombia, from the perspective of the Colombian Government, is a peace process underway with the two main guerrilla movements. President Pastrana was elected in 1998 with a strong mandate to end the civil conflicts, and a sizable civic movement called "No Mas" has marched in the streets of Colombian cities in the last two years demanding an end to violence. The talks with the FARC are further along than the negotiations with the ELN. Through negotiations with the FARC, last year the government agreed to a demilitarized zone in south-central Colombia, in Meta and Caquetá Departments (the zone, which is about the size of Switzerland, consists of about 4 percent of the country's land mass; 100,000 of Colombia's roughly 40 million people live 16 17 there). While the negotiations continue, the conflict goes on outside the zone. There has been no formal cessation of hostilities, and there are frequent military encounters between government forces and the FARC around the country. There are reasons to be cautiously optimistic that President Pastrana will make progress in these negotiations. Last winter, FARC leaders went on a three-week tour of European capitals. In part, the trip was designed to show FARC leaders, many of whom have been living in the jungle for decades, how the world has changed. It also exposed them to criticism from left-of-center politicians in Europe, who used the opportunity, I was told, to press the FARC leadership on its own violations of human rights and involvement in drug trafficking. Colombian officials believe the European tour will have a positive effect in the long run on the FARC position. While I was in the country, the FARC announced the formation of new political party-perhaps an indication that the guerrillas recognize the domestic political need to begin operating within the framework of normal politics. Just after my visit, the Colombian Government agreed to a demilitarized zone with the ELN, though the exact parameters of the zone, and the terms and conditions, have not been finalized. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES 1. Background and Colombian Government actions The dire human rights situation in Colombia has been well documented in the annual State Department human rights report, in reports by the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights office in Colombia, and reports by respected non-governmental organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. I do not attempt to repeat their findings or analysis here. It is enough to say that there is a crisis in the country: massive human rights violations are committed by the guerrillas, the paramilitaries, and to a lesser extent the Colombian Armed Forces. In recent years, there has been a measurable decline in the number of human rights violations directly attributable to the military. At the same time, violations by right-wing paramilitaries have increased, leading to the widespread belief in Colombia that the military collaborates with the paramilitaries-and lets them do their dirty work. In February, a Human Rights Watch report linked "half of Colombia's eighteen brigade-level army units (excluding military schools) to paramilitary activities." Their report concludes that "military support for paramilitary activity remains national in scope and includes areas where units receiving or scheduled to receive U.S. military aid operate." I discussed the human rights situation with the President, the Minister of Defense, and the U.S. Ambassador. I impressed upon them the importance of human rights issues in the Congress, and urged them to keep making efforts to improve the record of the Colombian Armed Forces. I emphasized to them the need to end impunity in the Armed Forces-that is, to prosecute all violators of human rights. The Colombian Government, at high levels, concedes that there is a human rights problem in the country, and has taken certain efforts to address it. These actions by the government are commendable, but it must do more. It must continue to make human rights a priority. It must continue to send a message throughout the armed forces that institutional tolerance of paramilitary activity must cease. The actions take to date by the Government include: Firing of high-level officials: President Pastrana fired four Army generals in 1999 for collaboration with or failure to take action against paramilitaries. Despite those dismissals, many military officials who are under investigation for links to the paramilitaries- and some who have been found guilty by the civilian courts for violating human rights-continue to serve in the military, and some have even been promoted. A number of investigators working on cases linking the Army and the paramilitaries have been threatened and either forced to resign from their posts or to leave the country. According to Colombian officials, within the next six months, the head of the Armed Forces, General Tapias, will be given the authority to dismiss any officer tied to paramilitary groups without going through lengthy dismissal proceedings. This would give Tapias the same power that enabled General Serrano, the head of the Colombian National Police, to purge the police of human rights violators. This authority to clean house is often credited with professionalizing the police force and it is hoped that it will do the same for the military. New military penal code: the Colombian Government passed a new military penal code in August 1999, but it has yet to be implemented. This new code includes protections for soldiers who refuse to follow orders which would involve violations of human rights. It also creates an independent body, similar to the judge advocate general corps in the U.S. military, so that unit commanders will no longer be judging their own troops. The new code gives civilian courts jurisdiction over all "crimes against humanity" including genocide, forced disappearance and torture. Notably absent from this list of offenses, however, is murder. Law on forced disappearances: the new military code requires that forced disappearances be tried in civilian courts, but the law to implement it has been stalled. Though President Pastrana initially supported this policy change, in December 1999 he vetoed the necessary legislation due to his objections over certain provisions in the bill. As a result, forced disappearance continues to go unpunished in Colombia: very few of the more than 3,000 cases reported to authorities since 1977 have been resolved. The government has promised that the bill will move quickly during the current session of Congress. Recent decree on human rights: in March, President Pastrana signed a decree to create an inter-agency mechanism designed to provide "early warning" of potential massacres-so the government forces can act to prevent them. This mechanism will be coordinated by the Ministers of Defense and Interior, with the cooperation of Colombian law enforcement agencies and the Prosecutor General. The Minister of Defense will be charged with dispatching the military to secure areas where massacres are believed to be imminent. It is too soon to say whether this mechanism will be effective. 2. Discussions with human rights and UN representatives While in Bogotá, I met jointly with three representatives of nongovernmental organizations working on human rights issues, and representatives of two U.N. bodies-the High Commissioner for Refugees and the High Commissioner for Human Rights. All five individuals expressed concern about various aspects of Plan Colombia. They emphasized different points: that the Colombian Government had not demonstrated enough of a commitment to the internally displaced, that increased military assistance could lead to increased displacements, that there was a great need to reform the military and improve its human rights record, that the plan could undermine the peace process, and that the plan did not place enough emphasis on alternative development. I assured the group that the United States was firmly committed to human rights, and would continue to press the Colombian Government on these issues. I also pointed out, however, that the human rights situation in the country was unlikely to improve unless the United States was fully engaged with Colombia. In other words, U.S. engagement and assistance to Colombia would inevitably (because of U.S. emphasis on human rights) have a positive effect on human rights in Colombia, and the converse-U.S. disengagement-would not be helpful to the cause of human rights. One individual present responded by saying "I essentially agree with what you have said." 3. Need for additional political officers in the Embassy Currently, just one officer at the U.S. Embassy in Bogotá is designated to monitor human rights on a full time basis. While others in the political section also have responsibility for monitoring human rights, I believe more officers may be needed to focus exclusively on this matter. Under the "Leahy Amendment" to the Foreign Operations and Defense Appropriations Act, all members of Colombian military units receiving U.S. training must be vetted to assure that they have not been involved in gross human rights violations. Embassy staff must review available records on each and every individual to receive U.S. training. This is a painstaking and time-consuming task. Moreover, the scope of the human rights violations in Colombia requires constant monitoring and reporting. SCHEDULE OF MEETINGS Wednesday, April 19

Thursday, April 20

APPENDIXSTATEMENTS BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

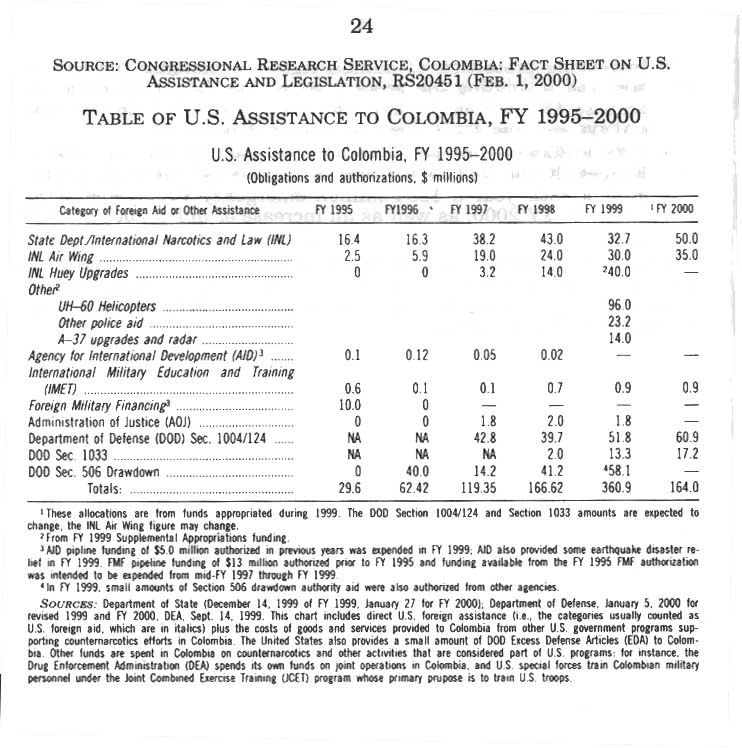

TABLE OF U.S. ASSISTANCE TO COLOMBIA, FY 1995-2000

DETAILED BUDGET REQUEST SUBMITTED BY CLINTON ADMINISTRATIONEXCERPT FROM INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL STRATEGY REPORT, DEPARTMENT OF STATE, MARCH 2000WORLDWIDE ILLICIT DRUG CULTIVATION |

|

|

| Asia | | |

Colombia | | |

| |

Financial Flows | | |

National Security | | |

| Center

for International Policy |

LETTER

OF TRANSMITTAL

LETTER

OF TRANSMITTAL