|

| Cuba Home | | |

About the Program | | |

News | | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Last

Updated:2/1/06

|

|

CIP International Policy Report: Sanctuary for Terrorists? - January 2006

Copies of this report are available for $2.50 each, or $1.00 each for orders of 20 or more, from the Center for International Policy. Request copies by e-mail at cip@ciponline.org. This report is also available in printer-friendly, easier-to-read Adobe Acrobat (.pdf) format. Sanctuary

for Terrorists? By Wayne Smith, Shauna Harrison and Sheree Adams Summary

Declassified CIA and FBI documents leave no doubt that Bosch and Posada were then involved in acts of terrorism, such as the bombing of a Cubana airliner in 1976 with the loss of 73 innocent lives. Bosch was also reported to have been behind the 1976 assassination in Washington of former Chilean diplomat Orlando Letelier and his American assistant, Ronnie Moffitt. And Posada acknowledged to The New York Times that he was responsible for the 1997 bombings of tourist hotels in Havana, resulting in the death of an Italian tourist and the wounding of several other people. These were but the tip of the iceberg. There were many other exile terrorists, many other assassinations and other acts of violence against Cuban- Americans who disagreed with the exile hardliners, in addition to intense efforts to intimidate those advocating dialogue with Cuba and/or those who insisted on traveling to the island. Most disturbingly, almost none of these terrorist acts, even those in the U.S., have been punished by U.S. authorities. On the contrary, there has been a clear pattern of tolerance. Orlando Bosch, for example, despite all the evidence against him, was pardoned by the George H.W. Bush administration—at the specific request of Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and now-Governor Jeb Bush. Thus, Bosch has lived freely and unrepentant in Miami since 1988. And now comes Posada Carriles. In prison in Panama on charges growing out of his intention to assassinate President Fidel Castro during a visit there, he, along with three other exile terrorists, was pardoned in August of 2004 by the outgoing president of Panama, Mireya Moscoso, at the request of Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and Congressmen Lincoln and Mario Diaz-Balart. Posada returned to the United States in March of this year. The authorities at first made no efforts to apprehend him, then arrested him for the minor charge of illegal entry. They have so far refused to honor the Venezuelan government’s demand that he be extradited and tried in the case of the 1976 Cubana airliner bombing. Posada remains in light custody, with the final disposition of his case still to be decided. At this point, however, it can be said that he clearly has received preferential treatment. As in the case of Orlando Bosch and many others, how is that preferential treatment consistent with our global campaign against terrorists and terrorist activities?

We agree with the congresswoman. Indeed, her statement quoted above, which was in response to the terrorist attacks on the London subways, is the theme of this conference. We would only add that “anywhere in the world” includes terrorist activity in, or emanating from, Miami. As Jim Defede, a former columnist for The Miami Herald, asked in a July 11 column taking issue with an earlier statement of hers condemning the “barbaric” terrorist attacks in London: “Where was the congresswoman’s outrage when she came to the defense of Luis Posada Carriles, a man who bragged about masterminding a series of hotel bombings in Havana that killed an Italian tourist? A man suspected of blowing up a Cubana airliner? Where was her desire to ‘neutralize terrorism’ when she pleaded two years ago with the president of Panama to release Pedro Remón, Guillermo Novo and Gaspar Jiménez (as well as Posada Carriles)?” Defede notes that she was joined in this effort by Congressmen Lincoln Diaz- Balart and Mario Diaz-Balart, who also urged the then-president of Panama, Mireya Moscoso, to release the four men. All had been convicted in Panama of endangering public safety, a charge stemming from an alleged plot to blow up a university center which Fidel Castro was scheduled to visit. All had other terrorist activities on their records as well. Remón had pleaded guilty in 1986 to trying to blow up the Cuban Mission in New York. Novo was convicted in the 1976 murder of Orlando Letelier and Ronnie Moffitt in Washington, D.C., though the conviction had been overturned on appeal. Jiménez had served six years in prison for trying to kidnap a Cuban diplomat in Mexico. U.S. federal prosecutors also indicted him for placing a bomb in the car of Miami radio commentator Emilio Milian, who lost both his legs as a result, though the indictment was quashed on a technicality.

Congresswoman Ros-Lehtinen was also involved in the case of Orlando Bosch, who, along with Posada Carriles, was accused of masterminding the downing of the Cubana airliner in 1976, with the loss of 73 lives. He was indicted and spent years in a Venezuelan prison, but was released under mysterious circumstances in 1987 and returned to Miami in 1988 without a visa. The Immigration and Naturalization Service began proceedings to deport him. The associate attorney general argued in 1989 that: “The security of this nation is affected by its ability to urge credibly other nations to refuse aid and shelter to terrorists. We could not shelter Dr. Bosch and maintain that credibility.” But shelter him we did. Urged by Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, then running for Congress, and by Jeb Bush, then managing her election campaign, President George H.W. Bush’s administration approved an administrative pardon for Bosch, who now lives unrepentant in Miami. Jeb Bush, meanwhile, has become governor of Florida.

President George W. Bush follows the pattern. Though he has

often said that anyone who harbors a terrorist is a terrorist,

his administration has handled the case of archterrorist Luis

Posada Carriles as though the latter had simply entered the

U.S. illegally. They, in effect, have “harbored”

him. This tolerance toward terrorists and acts of terrorism,

seen not just in the cases discussed above, but in dozens of

others, seriously undermines the U.S. campaign against terrorism

in the world at large. We cannot credibly ask other governments

not to harbor or assist terrorists if they see that in some

cases we are doing exactly that. Panel

One Chair

– Dick Russell, author Dick

Russell Many of those suspected in the wave of bombings and murders in Miami had received their training from the CIA. He well remembered a conversation he had in 1976 with James Angleton, the former head of counterintelligence in the CIA, about the chaotic situation developing in Miami. The concept of having a CIA base in Miami had seemed a sound one when it was opened, Angleton had said. It was something of a forward base in a Latin environment for operations in Latin America and especially in Cuba. But it got out of hand. When you have a large operation, but then the target, in effect, shrinks, and you begin to scale back, the question of what you do with the now larger-than-needed staff is always a problem. And it certainly was in this case. Much of the violence in Miami was the direct result of that situation. Peter

Kornbluh

People who don’t want to face the truth in these cases, Kornbluh noted, and especially in the case of the Cubana flight, always attribute them to someone else. It was Fidel Castro, they will say, or that one group of exiles did it and then blamed it on others. Or, they will say, the documents were forged. But we have here this afternoon, he noted, a series of intelligence documents, CIA and FBI reports, which are without question authentic. Most were written at the time of the events themselves, not years later. They were secret for many years, but were then reviewed and eventually declassified as the result of the Kennedy Assassination Records Act. The intelligence documents were still secret, however, at the time Orlando Bosch and Posada Carriles were tried in Venezuela, so they were not given to Venezuelan courts, nor to Cuba or Panama. A whole series of legal issues explains why the documents are not part of the present court case against Posada in Venezuela. But Kornbluh emphasized that U.S. officials reviewed them in the late 1980s, when Orlando Bosch was in Miami and fighting deportation. Those officials came to the conclusion that the reports were authentic, that Bosch was dangerous, was guilty of terrorist acts and should be deported. But he was not. The first document Kornbluh presented reported that Cuban exile groups devoted to violence held a meeting in Santo Domingo in June of 1976 and formed a group called CORU, or the Coordinadora de Organizaciones Revolucionarias Unidas (Coordinator of United Revolutionary Organizations), which the FBI classified as a terrorist umbrella organization. Orlando Bosch was its leader. These groups decided to carry out a series of terrorist attacks, in Miami, Trinidad, Guyana, and Mexico, culminating with the bombing of the Cubana airliner. According to evidence from multiple sources, both Orlando Bosch and Luis Posada Carriles were involved in this bombing. The second document Kornbluh presented made it clear that the FBI had evidence from 1965 forward that Orlando Bosch was involved in terrorist operations, at that point in the pay of the CIA. The document also revealed that Jorge Mas Canosa, head of the Cuban American National Foundation, had given money to Luis Posada Carriles to bomb ships in the Gulf of Mexico. The next document demonstrated that, ironically, the first evidence of Posada Carriles’ involvement in the bombing of the Cubana airliner came from our own FBI attaché in Caracas, who gave a visa to one of the two Venezuelans who put the bomb on the plane. The latter arrived with a letter from Posada Carriles asking that the bearer be given a visa for a photography mission. The same man had come in earlier actually asking for FBI assistance in violent activities against Cuban targets in Venezuela. Knowing that, one might have expected the visa to be refused. Had it been, the bombing might not have taken place. At that point, however, there was still a certain sense of common purpose between U.S. officials and anti-Castro groups, so the visa was given. This was the cause of some embarrassment within the U.S. government and there were a number of internal memos trying to explain what happened. Within 24 hours after the bombing, the FBI had reports that Venezuelan Intelligence (SIP) was scrambling to get Bosch and Posada out of town and that their sources confirmed that CORU was indeed responsible for the bombing. They also had reports of a fund-raising dinner in Caracas for Orlando Bosch at which he took credit for the assassination in Washington of Orlando Letelier and Ronnie Moffitt a few days earlier. Posada Carriles was quoted as saying they are going to hit a Cuban airliner. This report was taken very seriously within the U.S. Government, though there is no indication that they acted upon it. Kornbluh

indicated another report from the late 1970s based on conversations

with Orlando Garcia, of SIP. Both Orlando Bosch and Posada Carriles

were in prison in Venezuela at this point. Garcia said they

would be released. Garcia said he had no doubt that they had

conspired, and that they had been involved in the bombing. But

SIP was working hard to get them out. In other words, the fix

was already in. Ann

Louise Bardach

Why had Posada called? Why did he want to be interviewed? Bardach said it seemed clear to her that he wanted to draw attention to the 1997 bombing campaign against tourist hotels in Cuba, a campaign that he freely acknowledged he had engineered and which had resulted in the death of an Italian tourist. The purpose of the bombings was to shut down the Cuban tourist industry and discourage investments, but he felt that could only be achieved with publicity. He gave the interview in hopes of warning investors and tourists not to go to Cuba. Posada said it was too bad about the Italian tourist, who had simply been at the wrong place at the wrong time. Still, he “slept like a baby”: his conscience was clear. Posada also talked a good deal about the money trail, the sources of funds for his operations, including the bombings. Much of it, he said, came from various leaders of the Cuban American National Foundation. Not from the CANF itself, but from individuals such as Jorge Mas Canosa. The other thing Posada talked a good deal about was the 1976 bombing of the Cubana airliner in which, he insisted, he was not involved. The interview, when it was published in The New York Times, drew tremendous attention. Strangely, Posada at first denied he’d even given the interview or that he even knew who Bardach was. The New York Times pointed out that it had six hours of tape and noted that Larry Rohter, the Latin America bureau chief, had been present also. Eventually, Posada gave up on the denials. And he soon had bigger problems anyway, for shortly afterward, he was arrested in Panama with three Cuban exiles, all there to assassinate Fidel Castro, who was to give a public speech at a sports arena. Given the amount of C-4 explosives they intended to use, the carnage would have been tremendous. The fix seemed to be in again, however, for the four were tried on the lesser charge of public endangerment, and then, thanks to the interventions of Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and her two colleagues, Congressmen Lincoln and Mario Diaz Balart - all of whom appealed to then-President Mireya Moscoso - the four were pardoned and are all now back in the United States. Posada did not immediately return, however. He didn’t show up until last March. Bardach emphasized that from what she knew of Posada, who was a very careful character, he would not have come back had there not been some signal from “on high” that it was “ok.” She didn’t know who would have sent the signal, but she felt it was unlikely that he would have come without it. Eventually, he ended up in El Paso before an immigration judge, Bardach noted. She was sent to cover the case. The most intriguing thing about what happened in El Paso, she said, was “where was the government’s case?” They made no case at all against Posada. It was as though they were not participants. They cited her articles and various other open sources, but where were their own documents, the CIA and FBI reports, by then declassified? Nowhere to be seen. When they cited her New York Times article, and Posada was asked about it, he said it had been in English, which he barely spoke. A strange thing to say, since he had been an English language translator! About Posada’s relationship with Orlando Bosch, there was a point early on at which Posada was informing on Bosch to the CIA. He, for example, told them of a plot on Bosch’s part to assassinate Henry Kissinger. He also informed them of the plot to blow up the Cubana airliner. A strange thing to have done as he also was supposedly involved. Panel

Two Chair – Wayne Smith, Center for International Policy

Panelists

The

Letelier-Moffitt assassination Until September 11, 2001, this assassination was considered the most egregious act of international terrorism ever committed in the nation’s capitol. According

to a declassified intelligence report, an informer, whose name

was redacted from the report, overheard Orlando Bosch acknowledge

his involvement in the Letelier assassination at a reception

in Caracas. And in an October 10, 1976, a State Department cable

sent from the U.S. ambassador to Venezuela back to Washington,

the ambassador indicated that Bosch had been arrested. Immediately

after his arrest, Bosch said associates working under him for

CORU and the Chilean secret police had been responsible for

the assassination. Max Lesnick alluded to acts of terror committed against his person, but focused on Luis Posada Carriles.

Two individuals, a Cuban and a Venezuelan, know the truth about the bombing of the Cubana flight that left 73 dead. Carlos Andres Perez, the former president of Venezuela, and the widow of Orlando Garcia, a Cuban, know the truth. According to Perez, everything pertaining to the bombing has been taped and written down. At some point, someone will decide it is time for the truth to be known and the information will be revealed. This secret should not go to the grave. Historically, Cuban exile business owners have financially supported terrorism in South Florida and abroad. It is the main task of lobbies to make corruption possible with protection to achieve their means. Lesnick concluded, “terrorism cannot be classified as good and bad; the good ones are ours and the bad ones are theirs. Terrorism of any stripe is evil. In order to face this monster, you cannot befriend Bosch or Posada.”

Max Castro Impeding freedom of expression by acts of violence Castro described the driving force behind terrorism in Miami as the confluence of the U.S. government and extreme right-wing Cuban-Americans. In a tight embrace, they have targeted individuals advocating moderation of U.S.-Cuba policy. The relationship is fueled by the desire for regime change in Cuba. Impunity is given to individuals engaged in acts of terrorism against Cuba or against individuals here calling for engagement between the U.S. and Cuba. In the early days after the Cuban Revolution, the U.S. government and exiles combined efforts by engaging in raids against Cuba. During Operation Mongoose, the U.S. government trained Cuban exiles to launch raids against targets in Cuba. When the operation failed to produce regime change on the island, the government pulled the plug, forcing exiles to shift from state sanctioned agents to free-lancers. During the Reagan administration, Washington shifted from a strategy based on terror and brute force to one that took advantage of the lobbies in the Capitol to change policy at home. Exiles shifted from agents of the operation to architects of change in Cuba, fueled by the five Cuban-American members of Congress. Ironically, if it were not for the unrelenting drive of these members, we probably would not have the policy we have today. Although this strategy succeeded in tightening the embargo on Cuba, they failed to achieve their objective of regime change on the island. Political and ideological control in Miami replaced the use of physical terror by the exile community. Terrorist attacks on soft targets subsided as Miami shifted to a model that was based on political and ideological control of the community. Terrorist attacks were replaced by institutionalized violence to prevent the free flow of ideas.

While they succeeded in obtaining political control in Miami, tensions erupted within the exile community as Representative Lincoln Diaz-Balart rashly suggested a naval blockade of Cuba in response to an immigration situation. Exiles demonstrated control over ideology by closing the Cuban Research Institute, a leading think-tank that was headed by Lisandro Perez at Florida International University. And Max Castro’s own column was cancelled at The Miami Herald. Against recommendations from the Department of Justice and Henry Kissinger, former president George H. W. Bush offered impunity to Orlando Bosch by giving him an administrative pardon. According to Bush Sr.’s Justice Department, Bosch had participated in more than 30 terrorist acts. He was convicted of firing a rocket at a Polish ship that was on passage to Cuba and he was also implicated in the 1976 bombing of the Cubana flight. Last summer, the current administration continued to demonstrate its willingness to offer impunity to Cuban exiles who participate in acts of terrorism, as it failed to develop a strong case against Luis Posada Carilles in his immigration proceedings, even though the information against him exists. According to Castro, three processes could change the status quo in Miami: regime change in Washington, D.C. leading to less alignment with hardliners in Miami; a shift in demographics in South Florida as more moderate Cuban-Americans are able to vote; and/or significant change in Cuba. Under these scenarios, we are likely to see an end to the current relationship between the administration in Washington and the hardliners in Miami.

Attacks against radio stations Francisco Aruca is a Cuban-American who came to the United States in 1962 after escaping from one of Castro’s prisons where he had been confined since 1961. Aruca said terrorism in south Florida, specifically in Miami, began with bombs exploding in businesses that supported a dialogue with Cuba. Aruca described the community’s shift from fear of losing one’s life from exploding bombs to fear of losing one’s livelihood at the hands of institutionalized social pressures that developed as the bombings subsided. Supporters of the embargo have long used fear as a tactic to maintain control over the population. Aruca became a target of the violence in 1989 when two bombs exploded in the offices of Marazul, a travel agency that booked trips to Cuba and a sponsor of Aruca’s radio program. Unwilling to give up, Aruca and his board shifted to an AM frequency and developed a new program, Radio Union, which aired five hours per day. The program included musical programming from Cuba and employed a sales person to develop relationships with companies outside the travel industry to advertise on the air. Within three weeks, every sponsor pulled their advertisements from the station because they had received threats that their markets were at risk, not because they were unhappy with Radio Union. In 1994 Marazul suffered financial hardship as most of the flights to Cuba were grounded due to the suspension of all Cuban-American travel to Cuba by the Clinton administration. Two months after the regulations went into effect, Marazul canceled Radio Union because it could no longer sustain it financially. Supporters

of the embarge realized they could silence their opponents by

tightening travel restrictions, which hurt the travel industry.

They assumed that if people could no longer travel to Cuba,

resources would dry up and the radio programs would be canceled.

Chair – Francisco Aruca, Radio Progreso Panelists Bob Guild spoke about the wide range of efforts employed by Cuban exile extremists meant to forcefully dissuade people from traveling to Cuba. Historically, limitations on travel to Cuba have involved institutionalized control on the part of the U.S. government and fear at the hands of a violent minority. As part of the Cuba travel industry, Guild has experienced firsthand the tension and violence surrounding travel to Cuba. He has also taken part in a vigorous movement to resist the executive ban on travel in order to reunite families and to promote exchange and understanding. In 1958, in the case of Kent v. Dulles dealing with the travel of Americans to communist countries during the Cold War, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the right to travel is an inherent element of liberty that the government can regulate but cannot abridge in terms of U.S. constitutional rights.1 A few years later, because of the Castro regime’s ties to the Soviet Union, the Kennedy administration announced a total embargo on trade with Cuba. As a result, travel became regulated by the Department of Treasury as the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued a set of prohibitions which effectively banned travel by prohibiting any financial transactions with Cuba. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, however, many citizens, especially students, resisted the ban by traveling to Cuba. Notably, since 1969, the Venceremos (We Shall Overcome) Brigade has sent several thousand United States citizens to Cuba to participate in work projects as an act of solidarity with Cuba and of resistance to the United States government. When President Carter lifted the travel ban in 1977 by issuing a general license for travel-related transactions for those visiting Cuba, Guild, at the front of the Cuba travel industry, sent the first unrestricted group to the island. After a decade, when the embargo had not produced the hardline Cuban exile community’s desired effect on the Castro regime, terrorist organizations such as Omega 7 and CORU were formed. These terrorist groups attempted to frighten travelers and cripple the Cuba travel and tourism industry by placing bombs and carrying out assassinations of travel advocates. In the late 1970s, Omega 7, a terrorist organization founded in the U.S. by veterans of the Bay of Pigs invasion, assassinated Eulalio Jose Negrin, a Cuban activist in Union City, New Jersey and Felix Garcia Rodriguez, a Cuban diplomat assigned to the Cuban Mission to the United Nations.

Bombings directed at those who advocated travel between the U.S. and Cuba took place throughout the 1970s and 80s. Former CIA operatives, including Orlando Bosch, founded the CORU terrorist organization, which soon became involved in more than 50 bombings. These acts included the bombing of the Miami International Airport in 1975 (later attributed to Bay of Pigs veteran Rolando Otero Hernandez) and the bombing of a Cubana Airlines flight. However, the extreme violence surrounding Cuban issues did not prevent the formation of the Committee of 75, a group of Cubans living in the U.S. who shared a commitment to dialogue and understanding. The important dialogue that took place helped start travel agencies, such as Marazul, to provide services to Cuba and the travel of tens of thousands of Cuban-Americans to visit their relatives on the island beginning in 1979. Max Castro noted that although the case has not been resolved, the murder of Cuban-born director of Viajes Varadero Carlos Muñiz Varela is attributed to CORU by Muñiz Varela’s friends and family.2 Muñiz Varela, also a member of the Cuban-American dialogue group Committee of 75 and the Antonio Maceo Brigade, was only 26 and a father of two young children at the time of his murder. According to Castro, many activist groups continue to seek justice for the victim, and in 2004 U.S. Congressman José Serrano petitioned the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to reopen the murder investigation, at the request of the victim’s family.3 In 1982, the Reagan administration re-imposed travel restrictions that eliminated ordinary tourist and business travel and provided for only certain categories of travel, such as that by government officials, researchers, and people visiting close relatives. The Supreme Court’s decision in 1984 on the case of Regan v. Wald asserted that the executive branch had the authority to re-impose the restrictions based on its understanding of national security, and that this authority superseded freedom to travel under the Fifth Amendment. Immediately following this ruling, the Treasury Department served Marazul with two subpoenas—demanding the names and addresses of all persons who had traveled to Cuba since April 1982, information on the founding and structure of the company, and the names of about one thousand lawyers to whom Marazul had mailed brochures for a legal conference to be held in Cuba. Francisco Aruca, the founder of Marazul, faced a maximum penalty of ten years in prison and $50,000 in fines. Fortunately, strong public opposition, including a critical media reaction to the Treasury’s action, forced the Treasury to drop their demands. However, these charges still exist on record as criminal penalties, in contrast to the civil penalties commonly used today. The Clinton administration tightened and then loosened U.S. restrictions on travel to Cuba. In 1993, the administration added two categories of travel, for “clearly defined educational or religious activities” and for “activities of recognized human rights organizations.”4 The following year, in response to a spike in Cubans fleeing to the U.S., President Clinton announced measures that limited family visits to cases of extreme hardship, which would be eased by 1995. Persons visiting relatives in Cuba could make one trip annually without having to apply to OFAC for a specific license. A few months later, when Cuban fighter jets shot down two U.S. civilian planes, Clinton suspended indefinitely all charter flights between Cuba and the U.S., forcing licensed travelers to travel to Cuba via a third country. Following Pope John Paul II’s momentous trip to Cuba in 1998, Clinton announced that direct charter flights to Cuba would be resumed. Meanwhile, U.S. citizens continued to resist the restrictions during the Clinton administration: the Venceremos Brigade continued to send yearly contingents, Pastors for Peace initiated its unlicensed humanitarian caravans in 1992, Global Exchange launched its travel challenges in 1993, and the largest single travel challenge took place in 1997 when 900 unlicensed young people participated in the World Youth Festival in Havana. The latest travel restrictions imposed under President George W. Bush’s administration further curb travel to Cuba by severely limiting educational travel, limiting visits of Cuban-Americans to immediate relatives once every three years under special license (with no exceptions for family emergencies). Historically, the government

has tried to make it difficult for Americans to travel to Cuba,

and terrorists try to instill fear in those who wish to travel

to Cuba. Current polls indicate that an overwhelming majority

of Americans believe that they have a right to travel to Cuba.

Both houses of Congress have voted to eliminate the enforcement

of the travel ban, but the amendments were removed from the

legislation by the leadership, in violation of the rules of

procedure. And while the number of Americans visiting Cuba has

decreased dramatically over the last two years because of the

tighter restrictions, the Cuba travel industry, academics and

students, religious and humanitarian institutions, the business

community, civil liberties organizations, many Congress members,

and various campaigns are pressuring the executive branch of

the U.S. to change the policy. At this rate, one day, the undercurrent

of resistance that runs through the Cuba travel issue will make

way for a policy that reunites families and friends and expands

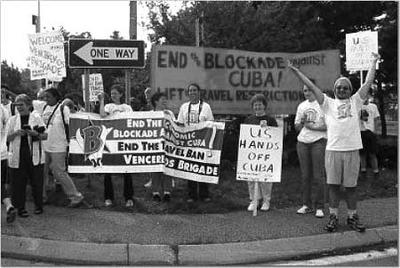

our freedoms as Americans and Cubans. Endnotes Photography Photograph 1 courtesy of Freedom Socialist, Vol 25, No 4, August-September 2005, “U.S. shelters anti-Cuba terrorist 10 Luis Posada Carriles,” by Doug Barnes, available at: < http:/ /www.socialism.com/fsarticles/vol26no4/carriles.html> (Last visited December 12, 2005). Photograph 5 courtesy of the

Young Communist League website, available at: <http://www.yclusa.org/

imagecatalogue/imageview/147/?RefererURL=/article/ articleview/1634/1/298>

(Last visited December 12, 2005). Conference Participants Ann Louise Bardach: Author of Cuba Confidential: Love and Vengeance in Miami and Havana and the editor of Cuba: A Traveler’s Literary Companion. Her Cuba Confidential was a finalist for the New York Public Library Bernstein Award for Excellence in Journalism and the PEN USA Award for Best Nonfiction, and was named one of the Ten Best Books of 2002 by The Los Angeles Times. Bardach was a staff writer for Vanity Fair for ten years and has since written for The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Los Angeles Times. She is the director of The Media Project at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Max J. Castro:

A sociologist, Castro is an independent researcher and writer

whose work appears regularly in the mainstream media, alternative

press and academic publications. From 1994 to 2003, he was a

senior research associate in the Dante B. Fascell North-South

Center at the University of Miami, and in the spring of 2004

was a visiting professor at Florida Atlantic University. Peter Kornbluh: A senior analyst at the National Security Archive, Kornbluh currently directs its Cuba and Chile documentation projects. He has edited and authored a number of Archive books, such as The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 and The Bay of Pigs Declassified: The Secret CIA Report on the Invasion of Cuba, both published by New Press. His articles have appeared in Foreign Policy, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Washington Post and many other journals and newspapers. In November of 2003, he served as producing consultant on the Discovery Times documentary, “Kennedy and Castro: The Secret History.” Max Lesnik: Lesnick now directs the program Radio-Miami every morning over Union-Radio 1450. Beginning in 1970, he was director of the weekly magazine Replica, which was the object of more than a dozen terrorist attacks because it advocated renewal of U.S.-Cuban diplomatic relations. Lesnik fought against Batista in the Escambray Mountains. He came to Miami in 1961 because he disagreed with the revolution’s growing alignment with the Soviet Union. Currently he is the general delegate of the Alianza Martiana, an organization which opposes the U.S. embargo. Dick Russell: Russell has written four critically-acclaimed books, including The Man Who Knew Too Much, a study of the Kennedy assassination, which was called “a masterpiece of historical reconstruction” by Publisher’s Weekly. His landmark article, “Little Havana’s Reign of Terror,” appeared in New Times on July 29, 1976. Wayne S. Smith: The former chief of mission at the U.S. Interests Section in Havana (1979-82), Smith is now a senior fellow at the Center for International Policy in Washington, D.C., and an adjunct professor at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he directs the Cuba Exchange Program. He is the author of The Closest of Enemies: A Personal and Diplomatic Account of the Castro Years. A publication of the Center for International Policy © Copyright 2006 by the Center for International Policy. All rights reserved. Any material herein may be quoted without permission, with credit to the Center for International Policy. |

|

|

| Asia | | | Latin America Security | | | Cuba | | | National Security | | | Global Financial Integrity | | | Americas Program | | | Avoided Deforestation Partners | | | Win Without War | | | TransBorder Project |

| Center

for International Policy |