CIP

International Policy Report: National Intelligence:

The dereliction of congressional oversight, May

2006

Copies

of this report are available for $2.50 each, or

$1.00 each for orders of 20 or more, from the Center

for International Policy. Request copies by e-mail

at cip@ciponline.org.

This

report is also available in printer-friendly, easier-to-read

Adobe Acrobat (.pdf)

format.

National

Intelligence:

The dereliction of congressional

oversight

By

Melvin Goodman

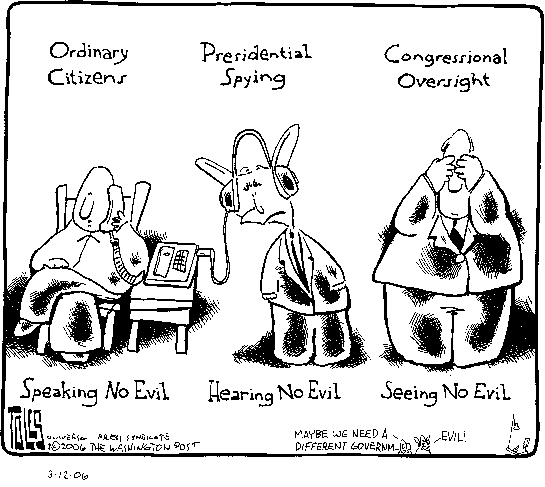

“There’s

a marked lack of curiosity around here.” Staff

member of House Intelligence Committee, 2005. 1

Oversight

is an essential aspect of democratic government, an

integral part of any system of checks and balances,

and central to any effort to “watch and control

the government.”2 Oversight is designed

to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the

government, to detect arbitrary and capricious behavior,

let alone illegal and unconstitutional conduct, to

ensure compliance with legislative intent, and to

prevent executive encroachment on legislative authority.

Currently the Senate and House intelligence committees,

which were created in the mid-1970s to ensure oversight

of secret agencies, are observing all of these duties

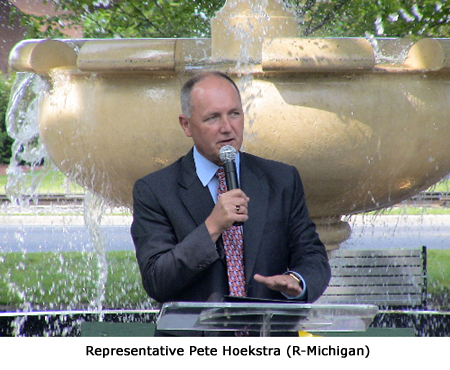

in the breach. Senate and House intelligence chairmen,

Pat Roberts (R-KS) and Peter Hoekstra (R-MI), respectively,

have become the cat’s paw of the Bush administration

and have made sure that there is no accountability

and no criticism of any actions of the intelligence

community that could redound unfavorably on the White

House.

Over

the years, the best-known examples of legislative

oversight are the investigations by select committees

into major scandals or failures. Recent examples of

select committee inquiries have included “Watergate”

in 1972-1974, intelligence agency abuses in 1975-1976,

the Iran-contra affair in 1987, and homeland security

in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Standing

committees have examined the sharing of intelligence

information prior to the 9/11 attacks and U.S. intelligence

on Iraqi WMD. But Congress’ current unwillingness

to investigate the torture and abuse scandals, CIA

secret prisons and extraordinary renditions, and the

NSA’s conduct of warrantless eavesdropping indicates

that the oversight process has atrophied.

There was no intelligence oversight from the agency’s

creation in 1947 until the creation of the Senate

and House intelligence committees in 1976. In the

very beginning, the intelligence community was under

the jurisdiction of the Senate and House Armed Services

Committees, but oversight was nonexistent and CIA

appropriations were hidden in the huge defense budget.

When CIA director Allen Dulles wanted $50 million

for a new headquarters building in Virginia, he visited

the chairmen of the Armed Forces and Appropriations

Committees and discussed what was needed. Dulles and

Senator Richard Russell (D-GA) drank bourbon and discussed

how many millions were needed, and Russell made sure

that Dulles left with more than was requested. The

CIA was involved in assassination plots, coups d’etat,

and various covert actions, but, according to Senator

Leverett Saltonstall (R-MA), “there are things

that my government does that I would rather not know

about.”3

It was not until 1975 that the Senate Select Intelligence

Committee (SSCI) and the House Permanent Select Committee

on Intelligence (HIPSI) were created. The decisive

event for the shift took place in 1973, when CIA director

Richard Helms deceived the Senate Foreign Relations

Committee, refusing to acknowledge the role of the

CIA in overthrowing the elected government of Chile.

Helms testified falsely that the CIA had not passed

money to the opposition movement in Chile, and a grand

jury was called to see if Helms should be indicted

for perjury. In 1977, the Justice Department brought

a lesser charge against Helms who pleaded nolo

contendere; he was fined $2,000 and given a two-year

suspended prison sentence. Helms went from the courthouse

to the CIA where he was given a hero’s welcome

and a gift of $2,000 to cover the fine.

In the wake of the Senate (Church Committee) and House

(Pike Committee) investigations of CIA abuses, the

center of gravity shifted on Capitol Hill and large

majorities in both houses favored the creation of

select committees. Senator Harold E. Hughes (D-IA)

and Representative Leo J. Ryan (D-CA) used the foreign

authorization bill to add a requirement that covert

actions, such as the operation in Chile, be reported

to Congress. According to the Hughes-Ryan Amendment,

covert actions could not be taken until a presidential

“finding” was reported to the Senate Foreign

Relations and House Foreign Affairs Committees as

well as the Armed Services and Appropriations Committees

of each house, which marked the first time that Congress

specifically ordered the CIA to report anything at

all.

The

Church and Pike Committees called for the creation

of congressional intelligence oversight committees

and, as a result, the Senate created the SSCI in 1976

and the House created the HPSCI in 1977. The era of

intelligence oversight began when these committees

claimed jurisdiction over the Hughes-Ryan amendment

to the Foreign Assistance Act in 1974. Initially,

the Senate Armed Forces Committee, the Senate Appropriations

Committee, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee,

and their House counterparts claimed equal oversight

jurisdiction. But, in 1980, the Carter administration

created the Intelligence Oversight Act that gave exclusive

jurisdiction for oversight to the SSCI and the HPSCI. The

Church and Pike Committees called for the creation

of congressional intelligence oversight committees

and, as a result, the Senate created the SSCI in 1976

and the House created the HPSCI in 1977. The era of

intelligence oversight began when these committees

claimed jurisdiction over the Hughes-Ryan amendment

to the Foreign Assistance Act in 1974. Initially,

the Senate Armed Forces Committee, the Senate Appropriations

Committee, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee,

and their House counterparts claimed equal oversight

jurisdiction. But, in 1980, the Carter administration

created the Intelligence Oversight Act that gave exclusive

jurisdiction for oversight to the SSCI and the HPSCI.

With the creation of the oversight committees, there

was no question that the Congress had the power to

monitor the performance of the intelligence community.

The committees had the power to legislate on all matters

related to the intelligence community. The intelligence

committees authorized the budget of the intelligence

community for action by the full Senate and had the

power to investigate allegations of criminality, intelligence

failure, and fraud and abuse. The committees could

monitor the operations of the community, including

covert actions, and audited all expenditures. Finally,

the Senate intelligence committee confirmed the most

senior officials of the intelligence community, and

received prior notification of covert actions after

the president had signed the “finding.”

The committees could task intelligence community officials

to supply sensitive information needed for oversight

through printed reports, letters, testimony, and briefings.

The

“Dysfunctional” Oversight Process.

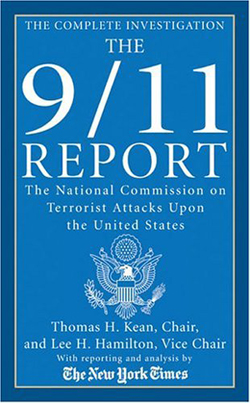

The

final report of the National Commission on Terrorist

Attacks Upon the United States (hereafter referred

to as the 9/11 Commission) was particularly critical

of the congressional oversight process, choosing to

call the process “dysfunctional,” which

is the same term the intelligence committees have

used to describe the CIA and the intelligence community.4

Over the past two decades, we have witnessed a series

of intelligence failures (e.g., the Soviet intelligence

failure, the Indian nuclear testing failure, 9/11

itself, and the run-up to the Iraq War), but there

has been no attempt by either the House or Senate

to consider serious reform.

Even with the creation of the tougher oversight process

in 1976, the CIA often chooses those events that it

does not share with the congressional committees.

In the early 1980s, CIA director William Casey did

not inform the committees that the CIA was mining

the harbor of Corinto in Nicaragua. Ten years later,

CIA directors William Webster and Robert Gates did

not inform the Congress that CIA spy Aldrich Ames

had compromised virtually every Soviet asset and every

Soviet operation. The agency also failed to inform

the committees that nearly all the major intelligence

information on Iraq in the run-up to the war in 2003

was single-source intelligence and that some of the

single-source items were from known fabricators. For

example, the agency failed to inform Congress before

its vote in October 2002 on the use of force that

the intelligence suggesting reconstitution of the

nuclear industry was a forgery and that the intelligence

on mobile biological warfare plants came from a single

source who was not trustworthy. (In February 2002

the Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency had

disavowed its intelligence on the so-called links

between Iraqi officials and al Qaeda because the single-source

in that case, a Libyan named al-Libi, was an established

liar. Nevertheless, CIA director Tenet disingenuously

assured the intelligence committees in October 2002

that there was evidence of links between Iraq and

al Qaeda.)

The

congressional intelligence committees neglected to

push for investigations of the abuse and torture of

detainees in CIA prisons and other overseas facilities.

Senator Carl Levin (D-MI) has won no Republican support

for his proposal to create an independent commission

to investigate treatment of detainees since 2001.

The administration’s rejection of accountability

for numerous cases of “cruel, inhuman, and degrading”

treatment of foreign detainees, and the congressional

failure to conduct oversight hearings, is a shocking

and shameful scandal in its own right. There has been

no investigation of Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld,

his senior

staff, and White House and Justice Department lawyers

who drafted or approved policies for detainee interrogations.

There has been no investigation of CIA personnel,

ranging from former director Tenet to operational

personnel in Afghanistan and Iraq, who have been involved

in the illegal hiding of “ghost detainees”

from the International Red Cross and the “rendition”

of suspects to countries that practice torture. As

a result, little or nothing is known about such CIA

practices as where prisoners are held, how many there

are, what access they have to medical treatment, and

how many may have suffered injury or death while in

the agency’s custody. The

congressional intelligence committees neglected to

push for investigations of the abuse and torture of

detainees in CIA prisons and other overseas facilities.

Senator Carl Levin (D-MI) has won no Republican support

for his proposal to create an independent commission

to investigate treatment of detainees since 2001.

The administration’s rejection of accountability

for numerous cases of “cruel, inhuman, and degrading”

treatment of foreign detainees, and the congressional

failure to conduct oversight hearings, is a shocking

and shameful scandal in its own right. There has been

no investigation of Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld,

his senior

staff, and White House and Justice Department lawyers

who drafted or approved policies for detainee interrogations.

There has been no investigation of CIA personnel,

ranging from former director Tenet to operational

personnel in Afghanistan and Iraq, who have been involved

in the illegal hiding of “ghost detainees”

from the International Red Cross and the “rendition”

of suspects to countries that practice torture. As

a result, little or nothing is known about such CIA

practices as where prisoners are held, how many there

are, what access they have to medical treatment, and

how many may have suffered injury or death while in

the agency’s custody.

The

dereliction of oversight reached its apogee in late

2002 when the Senate and House intelligence committees

made no serious attempt to vet the intelligence analysis

of the October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate

on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. Members of the

Senate intelligence committee had commissioned the

estimate, which is unusual in itself, but few members

took the time and effort to read the finished product

or to react to the CIA’s unclassified “white

paper” of the NIE, which omitted the caveats,

subtleties, and dissents from the classified version.

The White Paper was aimed at a domestic audience and

represented policy advocacy. The NIE said that Iraq

probably could not acquire a nuclear weapon for at

least seven years, but the White Paper left out the

dates and suggested that the weapon could be acquired

imminently. The NIE contained a dissent from the State

Department on this issue, but the White Paper omitted

the dissent. The NIE incorrectly stated that Iraq

was aggressive trying to obtain high-strength aluminum

tubes for its nuclear weapons program, and the White

Paper downplayed the dissent from the Department of

Energy, the most authoritative government agency to

report on such developments.

An

excellent example of the lack of interest and curiosity

of the oversight committees is the most recent oversight

failure. In December 2005, the New York Times reported

that the Bush administration ordered the National

Security Agency in 2001 to begin warrantless eavesdropping

of American citizens, a violation of law and possibly

the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution against “undue

searches and seizures.” Bush cited his inherent

constitutional authority as commander-in-chief and

the congressional resolution in the wake of the 9/11

attacks that authorized use of force. The president

and Attorney General Alberto Gonzales also argued

that they briefed Congress a dozen times on warrantless

wiretapping, but the briefings actually involved eight

of the 535 members of Congress. It took riveting testimony

to the SSCI in 1986 to break open the illegality of

the Iran-contra operation; it will take similar testimony

to get to the bottom of the executive order to sanction

the NSA’s use of warrantless eavesdropping against

American citizens.

What

Needs to be Done?

Reform

of the oversight process could be accomplished in

large part by enforcing the system that already exists.

The congressional intelligence committees have great

powers that have been increasingly observed in the

breach. The committees legislate on all matters relating

to the intelligence community, including the most

sensitive aspects of covert action; authorize the

budget of the intelligence community; investigate

allegations of failure and fraud, let alone criminality;

confirm key members of the community; and have access

to sensitive intelligence, including reports of the

Inspector General. The oversight committees may not

be able to veto a covert action, but it is possible

for them to deny the funding for specific covert actions.

It would be foolhardy for the White House and the

CIA to proceed with a covert action that Congress

opposed.

The 9/11 commission suggested important reforms for

the oversight process, but all of them were ignored

by the committees. The powerful rule of the Senate

intelligence chairman, Senator Roberts, moreover,

has kept the committee from investigating key areas

that point to an abuse of power by the White House

over the use of intelligence or by the intelligence

community itself. He recently promised once again

to hold “closed meetings to move forward”

on the administration’s manipulation of intelligence,

but gave no indication of when factual findings would

be published. With the exception of Senator Carl Levin

(D-MI), the Democratic minority has been extremely

dilatory in pursuing its legitimate interests on intelligence

matters. In the House, Representative Jane Harmon

(D-CA) has been no more aggressive than her Senate

counterpart, and has deferred unnecessarily to the

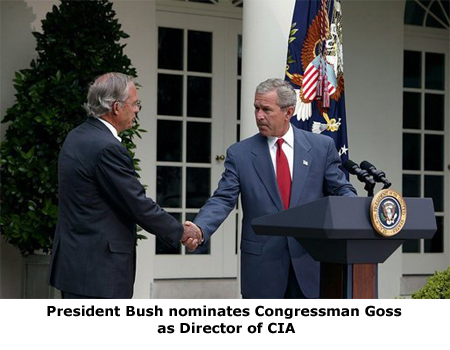

Republican chairman, Representative Hoekstra. In a

short period of time, Hoekstra has become the same

“advocate” for the intelligence community

that his predecessor, Representative Porter Goss (R-FL),

had been.

Aptly

Named “Oversight” Committee.

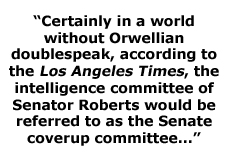

George Orwell certainly would have appreciated the

irony of referring to the SSCI as the oversight committee.

For the past fifteen years, there has been no end

to the examples of oversight on the part of the committee.

The Senate intelligence committee has failed to investigate

the major intelligence failures from the 1980s to

the Iraq War, including the failure to track the decline,

let alone collapse, of the Soviet Union; the Indian

nuclear test failures of 1998; and the failure to

monitor the terrorist campaign against the United

States that began with the bombing of the U.S. embassy

in Lebanon in 1983, when even high-ranking CIA officials

were killed. Certainly in a world without Orwellian

doublespeak, according to the Los Angeles Times,

the intelligence committee of Senator Roberts would

be referred to as the Senate coverup committee, although

the Senate oversight committee could serve as the

proper double entendre.5

Roberts has single-handedly kept the committee from

investigating the Bush administration’s use

of the CIA’s intelligence information in the

run-up to the Iraq War in March 2003 and the administration’s

warrantless eavesdropping program. Although the Bush

administration has resorted to a flimsy legal defense

to conduct warrantless surveillance, citing the authorization

to use force in Afghanistan in September 2001, Roberts

has done nothing to examine the NSA’s activity,

which is an obvious violation of the 1978 Foreign

Intelligence Surveillance Act, if not the prohibition

contained in the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution

against “unreasonable searches and seizures.”

President Bush and Senator Roberts are essentially

collaborating to get Congress to pass a bill ex

post facto to render the surveillance legal under

the previous FISA authority.

Roberts

also dragged his heels in investigating the bogus

intelligence of the CIA on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction

and finally relented only after an outside commission

headed by former senator Charles Robb (D-VA) and Judge

Larry Silberman was appointed to investigate the matter.

Roberts and former CIA director Porter Goss also collaborated

on the cover-up of the CIA Inspector General’s

accountability report on the 9/11 intelligence failure,

preventing proper distribution of the report within

the intelligence committees of the Senate and House

as well as a sanitized unclassified report, which

is customary in such events.

The

best example of the Senate intelligence committee’s

failure to pursue oversight of the executive branch

and the misuse of the intelligence community turned

on the issue of warrantless surveillance that surfaced

in December 2005. A secret intelligence court exists

to review classified applications for wiretapping

inside the United States, but President Bush signed

a secret executive agreement in September 2001 permitting

the NSA to monitor the conversations of American citizens

in the United States. Most Republican congressmen

favor an explicit authorization of such wiretapping

and an exemption of it from the 1978 law. The FBI

has already acknowledged that the NSA’s spying

inundated the FBI with thousands of leads that were

worthless.6

A

stifling partisanship within the congressional oversight

process meant that, for the first time since the intelligence

committees were formed in the mid-1970s, the Senate

failed to pass an intelligence authorization bill.

Former intelligence committee chairmen, such as Bob

Graham (D-FL) and David Boren (D-OK), remarked that

they had never witnessed such a high level of animosity

and partisanship. Ironically, former committee member

Senator Warren Rudman (R-NH) urged that “politics

should stop at the door of that committee,”

though it was Rudman who ushered in the era of partisanship

in 1991, when he accused CIA critics of the nomination

of Robert M. Gates for CIA director with “McCarthyism.”

Rep.

Hoekstra has maintained the same partisan lock on

the House intelligence committee that Roberts has

placed on the doors of the Senate intelligence committee.

Just as Roberts has blocked inquiries and investigations

of such illegal activities as warrantless eavesdropping

and torture and abuse at secret prisons, Hoekstra

has made sure that the House committee doesn’t

open any of these Pandora’s boxes. Ironically,

the House of Representatives has a procedure that

permits any congressional committee to obtain factual

information—not opinions—from the executive

branch.7 The procedure was used during the Vietnam War to obtain access to the “Pentagon

Papers,” the Defense Department study of U.S.-Vietnamese

relations, and information on CIA covert operations

in Laos.8 When the United States fought

a secret war in Cambodia during the Vietnamese War,

it took a congressional inquiry to learn the number

of U.S. sorties and the tonnage of bombs and shells

fired and dropped during certain periods. A month

before the Iraq War, Representative Dennis Kucinich

(D-OH) used a resolution of inquiry to obtain a 12,000-page

Iraqi declaration on its weapons of mass destruction,

which turned out to be far more accurate than CIA

declarations on Iraqi WMD. A resolution of inquiry

would be an effective device for gaining more information

on such controversial issues as CIA extraordinary

renditions and secret prisons, which Hoekstra refuses

to investigate.

the Vietnam War to obtain access to the “Pentagon

Papers,” the Defense Department study of U.S.-Vietnamese

relations, and information on CIA covert operations

in Laos.8 When the United States fought

a secret war in Cambodia during the Vietnamese War,

it took a congressional inquiry to learn the number

of U.S. sorties and the tonnage of bombs and shells

fired and dropped during certain periods. A month

before the Iraq War, Representative Dennis Kucinich

(D-OH) used a resolution of inquiry to obtain a 12,000-page

Iraqi declaration on its weapons of mass destruction,

which turned out to be far more accurate than CIA

declarations on Iraqi WMD. A resolution of inquiry

would be an effective device for gaining more information

on such controversial issues as CIA extraordinary

renditions and secret prisons, which Hoekstra refuses

to investigate.

Meanwhile,

the intelligence committees have not challenged the

efforts of the Bush administration to restrict the

need to know of the American people. In 1999, four

years after the Clinton administration signed a declassification

order, the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and

several other agencies began removing thousands of

historical documents from public access, including

documents that had been published by the State Department

and photocopied by private historians.9

Some of the documents were decades-old reports from

the Korean War and the early days of the Cold War.

The Bush administration accelerated the process when

it came into office, and the impact of the 9/11 attacks

put the program into high gear. The program has revoked

access to approximately 9,500 documents since its

inception, and more than 8,000 of these documents

have been removed since the Bush administration came

into power. There clearly has been a marked trend

toward greater secrecy in the Bush administration

that has increased the pace of classifying documents,

slowed declassification, and discouraged release of

some material under the Freedom of Information Act.

The CIA under Porter Goss went even further, denying

publication of materials that have no security classification

and preventing CIA officials from addressing open

meetings of academic associations. He also threatened

the possibility of grand jury investigations in which

reporters would have to reveal their sources of classified

information or risk prosecution for espionage.

Meanwhile,

the intelligence committees have done nothing to challenge

the efforts of the White House to shut off the flow

of national security information to the American public.

The White House and the Department of Justice are

even using an espionage law from the days of World

War I to prosecute two pro-Israeli lobbyists for receiving

classified information from a Pentagon official who

was sentenced to twelve years in prison in January

2006. The two lobbyists, Steven Rosen and Keith Weissman

of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, are

facing jail sentences that would have a chilling effect

on debate over national security issues. This would

represent the first time that any administration has

tried to stifle debate on national security issues

by criminalizing the receipt of oral information as

part of a lobbying or reporting process.

In addition to blocking any serious investigations

of the misuse of intelligence, the Senate and House

intelligence committees also have blocked the Government

Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress,

from monitoring the effectiveness of the nation’s

intelligence agencies. The GAO is uniquely qualified

to investigate the world of intelligence; it has more

than 150 officials who are able to audit intelligence

information, but it has not audited the CIA or the

NSA since the 1960s. In the mid-1970s, the Pike Committee,

which investigated the intelligence community recommended

that the GAO should have the same authority to investigate

and audit intelligence as other agencies. But the

GAO needs authorization from Congress to begin an

investigation, and the oversight committees have been

particularly quiet since the intelligence failures

that accompanied the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Both

Roberts and Hoekstra have stated that they have their

own audit staffs within the intelligence oversight

committees and have no need for GAO involvement.

Unless the congressional oversight process returns

to its bipartisan or nonpartisan roots, recruits an

expert professional staff with the instincts of junkyard

dogs, accepts the fact that objective, balanced intelligence

analysis is just as important as clandestine operations,

and appoints chairmen who do not see themselves as

“advocates” for the intelligence community,

the CIA and other intelligence agencies will not receive

the guidance and monitoring they sorely require. With

the dangerous increase in unchecked presidential power

and the incompetence of the intelligence community

prior to the 9/11 attacks and the Iraq War, the restoration

of congressional intelligence oversight is essential

to American national security.

Footnotes

1 Pat M. Holt, “Congress Partly to

Blame for Bush’s Warrantless Wiretaps,”

Christian Science Monitor, January 5, 2006,

p. 15.

2 John Stuart Mill, Considerations

on Representative Government, London: Parker,

Son, and Bourn, 1861, p. 104.

3 Mark M. Lowenthal, Intelligence:

From Secrets to Policy, Washington, DC: The CQ

Press, 2000, pp. 141-142.

4 See The Final Report of the National

Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States,

Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2004.

5 “Advise and Assent,” editorial,

The Los Angeles Times, February 19, 2006,

p. 6.

6 Lowell Bergman, Eric Lichtblau, Scott

Shane, and Don Van Natta, Jr., “Spy Agency Data

after Sept. 11 Led FBI to Dead Ends,” The

New York Times,

January 17, 2006.

7 Louis Fisher, “House Resolutions

of Inquiry,” Washington, DC: Congressional Research

Service, May 12, 2003.

8 Fisher, “Resolutions of Inquiry,”

p. 17.

9 Scott Shane, “U.S. Reclassifies

Many Documents in Secret Review,” The New

York Times, February 21, 2006, p. 1.

|