October 27, 2006

Counter-drug military construction projects in 2005

Here, thanks to a FOIA request, is a list of US-funded base construction projects paid for in 2005 with Defense Department counternarcotics funds.

It comes from a report, required by Congress in the 2006 Defense Authorization law, that was supposed to total Defense-budget counter-drug aid to every country in the world. For some reason, the report only includes Defense-budget counter-drug construction aid, which is only a fraction of what most countries' militaries get through the Pentagon's budget.

Nonetheless, the Western Hemisphere section below is worth a look.

SOUTHCOM

Bahamas (Caribbean Region) ($2.213M)

Company Housing and Furnishings/Facility Maintenance. Funding provided for company housing and the furnishings on an operating base in Georgetown, Greater Exuma Island. Also included is the maintenance of the operating facility. On this operating base, US. Army helicopter operations are conducted in support of Operation Bahamas Turks and Caicos Counter-drug. (PC2307) Total FY05 Funding: $2.213M Cost breakout is as follows:

- Base Construction funding ($1,400K)

- Operational funding ($312K)

- Furnishings ($441K)

- Facility maintenance/upkeep ($60K)

Bolivia ($0.590M)

Cochabamba Shoot House. Provided critical training facility for military and police CNT units undergoing U.S. training for operations. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.06M.

Caranavi Joint Task Force Base Camp. Project provided improved utilities, force protection, logistics support facilities and additional berthing to support establishment of a joint Bolivian CNT task force between national police, air force, and army engineer forces. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.45M.

Tocopilla Force Protection Improvements. Provided perimeter fence and lighting, guard posts, and other improvements to Bolivian navy outposts assigned riverine patrol missions. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.04M.

Colomi Army Camp Utilities Upgrade. Project provided water treatment and conditioning to domestic water supply to improve sanitation and health conditions at existing outpost. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.04M.

Colombia ($5.548M)

Training Facility located in San Andres, Colombia. Funding was provided to operate a training facility at the San Andres, Colombia radar site to train Colombian Air Force technicians in the skills needed to assume maintenance responsibilities for Hemispheric Radar System radar sites. FY05 funding supports English language training in Bogota and on-the-job training at each radar site and Bogota and associated force protection for supporting personnel. Funding also for the refinement of formal course training material, instructors, and development and implementation of on-job-training program. (PC4208) Total FY05 Funding: $1.08M

Puerto Leguizamo/La Tagua Road Improvements. Provided critical improvements to the only road link between these two forward outposts astride the Putumayo and Caqueta Rivers. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.800M.

Airfield Improvements to Tres Esquinas. Supported critical airfield used to support Plan Patriota operations. FY05 funds used to execute the design portion. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.150M.

Depot Level Maintenance Facility in Bogota. Supported establishment of a depot level riverine maintenance facility.

FY05 funds used to execute the design portion. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.080M.Improvements to CACOM 3 Apron and Taxiways. Supported the primary reception and staging site for U.S. units providing critical training to COLMIL forces and COLAF units supporting Plan Patriota IIB operations. FY05 funds used to execute the design portion. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.4M.

Ammunition Storage Point at Larandia. Provided critical ammunition storage capability for units assigned to JTF-Omega and directly supporting Plan Patriota. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.6M.

Runway Improvements at Juanacho. Project supported needed taxiway and ramp upgrades. Juancacho provides forward staging and support facility for JTF-Omega. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.3M.

Combat Training Center at Larandia. Provided a national training center for COLAR forces supporting Plan Patriota IIB and IIC operations. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.9M.

Riverine Facilities at Puerto Carreno. Project provided for extensive upgrades to include barracks, walkways, electrical, ramps, fuel storage, and maintenance. Project provided needed sustainment for Battalion 40 and COLMAR support to JTF-Omega. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.2M.

Electrical Upgrades at Larandia. Project completed upgrades to the Larandia electrical grid required as a result of the rapid expansion/growth of Larandia as a major technical/operationa1 base for the COLMIL. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.5M.

Tumaco Pier. Project provided essential staging and fueling point for COLMAR forces operating on the Pacific Coast. Project was primarily focused on the interdiction of drugs/arms traffickers using the river systems on the Pacific Coast as a staging base for illegal drug/arms movement. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.12M.

Puerto Leguizamo Airfield. Provided for critical repairs to the Puerto Leguizamo airfield. Repairs included runway,

taxiway, and tamp improvements needed to sustain this key forward operating base along the southern border of

Colombia. Puerto Leguizamo is the primary training and staging base for COLMAR operations in the Pase IIB area

of operations. Completed design work in FY05. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.08M.Tolemaida Force Protection Upgrades. Project provided for a perimeter fence to be constructed around the newly completed SF compound in Tolemaida. Project provided needed standoff distance and isolation from other facilities. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.2M.

4 Office Trailers/Facility Maintenance. Funding provided for 4 office trailers and the maintenance of the Forward Operating Site in Apiay, Colombia that conducts Joint ISR aircraft operations in support of Plan Colombia. (PC2416) Total FY05 Funding: $0.138M

Ecuador ($14.734M)

Forward Operating Location (FOL). Funding was provided to maintain and operate the FOL in Manta, which consists of 127 facilities of which 48 are buildings. FOL Manta provides a base of operations to facilitate counterdrug detection and monitoring operations within the USSOUTHCOM AOR. FOL Manta provides basing and logistical support for a steady state of six aircraft and 450 personnel with a capacity to surge to eight aircraft for two week periods. (PC9500) Total FY05 Funding: $14.134M. Cost breakout is as follows:

- Air Expeditionary Forces (Force Protection and Firemen) travel and per diem ($377K)

- Erosion project for runway required for CN missions ($607K)

- Supplies and equipment that can only be bought through the Standard Base Supply System ($233K)

- Communication personnel TDY from Headquarters ($54K)

- Procurement of AGE equipment ($142K)

- Base operating support contract ($12,721K)

Operational Support for the Northern Border. Project supported units assigned to Ecuadorian defense forces along the northern border with Colombia. Two projects programmed for design/construction in FY05. First project provided needed ammunition storage facility for the 39th Infantry Battalion in the Carchi Province. Second project provide critical force protection upgrades to the 55th Infantry Battalion assigned to the 19th Jungle Brigade. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.6M.

El Salvador ($0.925M)

Forward Operating Location (FOL). Funding was provided to maintain and operate the FOL in Comalapa. FY05 funding was provided for installation of water supply tank and fire pumps for autonomous fire suppression capability, procurement and installation of a generator and transfer switch for new warehouse/office building, electrical driveways to warehouse bays doors, upgrade pistol range, and lighting protection for the FOL. (PC9500) Total FY05 Funding: $0.925M.

Jamaica ($0.8M)

Pedro Cayes Water/Fuel Storage Facilities. Project provided for water/fuel storage facilities in support of Jamaican Coast Guard drug interdiction efforts against "go fast" targets. Supported both surface and helicopter assets directed against the "go-fast" threat. (PC9493) Total FY05 Funding: $0.8M.

Netherlands Antilles ($16.426M)

Forward Operating Location (FOL). Funding was provided to maintain and operate the FOL in Curacao. This FOL consists of 40 facilities of which 15 are buildings. FOL Curacao provides a base of operations to facilitate counterdrug detection and monitoring operations within the USSOUTHCOM AOR. FOL Curacao provides basing and logistical support for a steady state of six aircraft and 250 personnel with a capacity to surge to eight aircraft for two week periods. (PC9500) Total FY05 Funding: $14.892M. Cost breakout is as follows:

- Air Expeditionary Forces (Force Protection and Firemen) travel and per diem ($2,153K)

- Contract lodging permanent party ($266K)

- Supplies and equipment that can only be bought through the Standard Base Supply System ($220K)

- Engineering study for fire station shelter in Curacao ($77K)

- Contracting support for FOL oversight ($470K)

- Base Operating Support contract ($11,706K)

Forward Operating Location (FOL). Funding was provided to maintain and operate the FOL in Aruba. This FOL

consists of 1 facility which is a building. FOL Aruba provides an overflow capability to facilitate counterdrug detection and monitoring operations within the USSOUTHCOM AOR. FOL Aruba provides communication and contracting support to aircrews. (PC9500) Total FY05 Funding: $1.534M. Cost breakout is as follows:

- Bandwidth expense ($500K)

- Civil engineering/contracting support to building/ramp projects ($552K)

- Direct support to include Air Expeditionary Forces Communication person per diem and travel, lodging, environmental baseline study, and miscellaneous contracts ($430K)

- Air Combat Command Program Management System expense ($50K)

- Base operating support contract support ($2K)

Peru ($0.175M)

El Estrecho Navy Forward Operating Base. Project increased berthing and life support at remote outpost conducting riverine interdiction and joint operations with national police. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.1M.

Mazamari and Lima Small Arms Ranges. Project repaired and upgraded small arms ranges used to train counterdrug police conducting infiltration, interdiction, and associated counter-terrorism missions. (PC9201) Total FY05 Funding: $0.075M.

Posted by isacson at 04:47 PM | Comments (0)

October 26, 2006

10,393 Colombian military trainees in 2005

The State and Defense Departments have finally released, and posted to State's website, the Foreign Military Training Report covering 2005. There, you will find out that the United States gave military, police, or defense-policy training to 10,393 Colombians last year. That is over 1,500 more trainees than in 2004, though short of the 2003 high of 12,947.

The report's statistics portray Colombia as the number one recipient of U.S. military training in the world. The report, however, severely under-reports training in Iraq and Afghanistan - either because training of those countries' security forces is classified, or because budgeting does not separate such training from the cost of U.S. military operations in those countries. So Colombia was, in fact, the second or third largest U.S. training recipient last year.

Nonetheless, the report makes clear that no other Latin American country came close to Colombia in 2005 (in fact, no other country in the hemisphere even exceeded 1,000 trainees).

A big PDF file identifying courses given and recipient military units is available here by clicking on "Western Hemisphere."

Posted by isacson at 11:52 PM | Comments (0)

October 25, 2006

Nicholas Burns: No cut in aid - but less "cheerleading"

In a sit-down last week with reporters, the outgoing head of U.S. Southern Command, Gen. John Craddock, said that reductions in aid to Colombia were on their way. Added the Associated Press, "Craddock said Colombia's defense minister, Juan Manuel Santos, is in agreement with reductions in U.S. military funding."

This was the latest repetition of the idea that reductions in aid to Colombia - the first reductions in about fifteen years - would be forthcoming in the administration's 2008 budget request to Congress (which comes out next February). We have been told to expect less aid in the 2008 request during recent meetings with U.S. officials, and we have read it in recent press coverage, including a piece in Saturday's edition of El Tiempo:

An initial cut of a bit more than 50 million dollars is being discussed, which would go against accounts for the Police Carabineros program, the demobilizations and others. And while this is a small amount, compared to the annual total that is delivered (some 700 million dollars), it will increase with each passing year. In other words, from here to 2010 - the year in which Uribe will finish his second term - the country will be receiving a bit more than half of what it gets today.

And these are not speculations. The director of Narcotics Affairs at the Department of State, Anne Patterson, and the "drug czar," John Walters, said it in an interview with this newspaper. And the head of the Southern Command, John Craddock, repeated it this week.

The theory is that Colombia has begun "to turn the page," and that it is time for it to take on more responsibilities. "We have sustained aid levels for six years. It is logical to suppose, and this was the plan from the beginning, that we would arrive at a point where there would be reductions," says a source at the State Department.

Well, maybe not. It appears that plans to begin reducing U.S. aid next year have been shelved for now. That, at least, was the message of Nicholas Burns, the acting number-two official at the State Department, who is leading a seventeen-member delegation to Bogotá that arrived yesterday and leaves tomorrow. "'We intend to ask our Congress to maintain the current level of funding' for 2007 and 2008," Burns told reporters yesterday.

That apparent change of direction is the big story - so far - of the Burns visit, which is the biggest and highest-level U.S. delegation to visit Colombia in quite a while.

Also noteworthy are strong indications that Burns, Anne Patterson, Assistant Secretary for Western Hemisphere Affairs Tom Shannon, Drug Czar John Walters and others are not in Bogotá just to praise and celebrate Uribe and Plan Colombia. The U.S. officials also appear to be voicing some serious concerns about the policy's results, the human-rights climate, and the paramilitary process. Note these excerpts from a Reuters interview with Burns, which went on the wires a couple of hours ago.

"We think the counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics efforts have been very successful but there could be further progress."

"If the military is responsible for human rights violations then those people need to be held accountable, they need to be prosecuted."

"We think this [the "Justice and Peace" Law] is a necessary law ... we are in favor of the effort but there are some questions about whether some of sentences are too lenient, whether people who are responsible for horrible crimes are getting off too easily. ... It is up to Colombia to work through that but as we are funding some of these programs these questions are being asked."

Especially significant is that the U.S. officials did not come to Colombia bearing a new certification of improvements in the Colombian military's human-rights performance. By law, the State Department must issue two such certifications each year; 25 percent of that year's military aid remains frozen - it cannot be spent - until the certifications occur (each one frees up half of the frozen aid). No certification for any 2006 aid has yet been issued, largely due to concerns about military abuses and the inability to punish past cases.

Posted by isacson at 12:47 PM | Comments (2)

September 28, 2006

"Elephant-sized worry" in Colombia

Dare we say it? Today's Robert Novak column is actually worth a read:

The situation is summarized in a Sept. 19 memo by a well-informed source: ''The Colombian Army is hemorrhaging with problems. The chief problem is that we took a very mediocre barracks-bound military force, gave it some little amount of training and lots of equipment but never demanded the structural reform like we did with the Colombian National Police some 12 years ago . . . Everyone seems incapable of seeing the 'elephant in the room' and realizing that years of cooperation with the paramilitary forces have corrupted the Colombian Army officer corps all the way up, and the institution requires a dramatic house cleaning and structural reform . . .''

Posted by isacson at 06:21 AM | Comments (2)

September 26, 2006

Some updated U.S. aid numbers

We've just posted a big and long-overdue update to our estimates of U.S. aid to every country in Latin America. To see aid broken down further, with explanations of what each program does, visit www.ciponline.org/facts/country.htm.

In 2005, these were the top five overall recipients of U.S. aid in the Western Hemisphere:

Colombia

Haiti

Peru

Bolivia

Mexico

The above charts include four of the five top military aid recipients as well. Here is the fifth:

Ecuador

Again, more information - including the numbers themselves - is at www.ciponline.org/facts/country.htm.

Here is what aid to Colombia looks like since 2004. This table includes how the House and Senate versions of the 2007 foreign aid bill would affect aid amounts. The House and Senate appropriations committees have finished work on the 2007 aid bill, and the House has passed it. The full Senate has yet to consider the bill and appears to be unlikely to do so before the midterm elections in early November. A table going back to 1997 can be viewed here.

| Military and Police Assistance Programs (millions of dollars; numbers underlined and italicized are estimates taken by averaging previous two years) |

| | | | 2007, request | 2007, House version of foreign aid bill | 2007, Senate version of foreign aid bill | |

| International Narcotics Control (INC) State Department-managed counter-drug arms transfers, training, and services | 0 | | | 0 | 18.9 | 0 |

| "Andean Counterdrug Initiative" Basically the same as INC above, but separated out for the Andes | | | | 366.6 | 384.1 | 369.6 |

| Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Grants for defense articles, training and services | 98.5 | 99.2 | 89.1 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 |

| International Military Education and Training (IMET) Training, usually not counter-drug | | | | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| "Section 1004" Authority to use the defense budget for some types of counter-drug aid | | | | 161.0 | 161.0 | 161.0 |

| Emergency Drawdowns Presidential authority to grant counter-drug equipment from U.S. arsenal | | | | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antiterrorism Assistance (NADR/ATA) Grants for anti-terrorism defense articles, training and services | | | | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Demining (NADR/HD) Grants for landmine removal | | | | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Small Arms / Light Weapons (NADR/SALW) Grants to assist in halting trafficking in small arms | | | | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Counter-Terror Fellowship Program (CTFP) Grants for training in counter-terrorism through a Defense Department program established in 2002 | | | | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies (CHDS) Grants for education in defense management at a Defense-Department school in Washington | | | | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Excess Defense Articles (EDA) Authority to transfer "excess" equipment | | | | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Discretionary Funds from the Office of National Drug Control Policy | | | | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | 555.6 | 642.5 | 590.9 | 623.6 | 660.0 | 626.6 |

| Percentage of total | 80.5% | 82.7% | 81.2% | 82.5% | 82.3% | 82.5% |

| Economic and Social Assistance Programs (millions of dollars) |

| | | 2006, estimate | 2007, request | 2007, House version of foreign aid bill | 2007, Senate version of foreign aid bill | |

| International Narcotics Control (INC) State Department-managed counter-drug arms transfers, training, and services | | | | 0 | 7.3 | 0 |

| "Andean Counterdrug Initiative" Basically the same as INC above, but separated out for the Andes | | | | 132.3 | 0 | 132.9 |

| Economic Support Funds (ESF) Transfers to the recipient government | | | | 0 | 135.0 | 0 |

| P.L. 480 "Food for Peace" Humanitarian deliveries of food | | | | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | | | | 132.3 | 142.3 | 132.9 |

| Percentage of total | 19.5% | 17.3% | 18.8% | 17.5% | 17.7% | 17.5% |

| | | |||||

| Grand Total | 690.1 | 777.2 | 728.1 | 755.9 | 802.3 | 759.5 |

Posted by isacson at 05:47 PM | Comments (3)

September 24, 2006

Notes from last week's hearings

On Tuesday, the Senate Armed Services Committee considered the nomination of Vice Admiral James Stavridis to be the next commander of the U.S. Southern Command, which governs the U.S. military's activities in nearly all of Latin America and the Caribbean. (Adm. Stavridis, today's New York Times informs us, has been a regular squash partner of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.)

On Thursday, meanwhile, two House subcommittees met jointly to discuss "The Need for European Assistance to Colombia for the Fight against Illicit Drugs."

CIP Intern Mariam Khokhar attended both hearings. Here are her notes.

Committee on Armed Services

Senate Hart Building

Tuesday, September 19, 2006 9:30 am

Vice Admiral James G. Stavridis, USN

(For appointment to be admiral and to be Commander, U.S. Southern Command)

Adm. Stavridis shared a panel with Gen. Bantz Craddock, the current chief of U.S. Southern Command, who has been nominated to head the European Command. Stavridis' responses to senators' written questions are available as a PDF file.

Stavridis's opening statement

Stavridis stated that it is an honor and privilege to be considered and thanked the committee for their time. If confirmed, he said that "this job will receive my full energy and attention."

Committee Chairman Sen. John Warner (R-Virginia) asked Stavridis to explain the importance of Panama today.

Stavridis replied that the canal is very important, as 65% of the ships passing through the canal go to U.S. ports. The Panamanian president is seeking the public's approval for a new referendum to expand the canal. The money for this project will come from public and private investors. The United States has to follow especially the private investment in order to be aware of Chinese economic and military connections in Panama.

Sen. Warner added that the United States has to respect Panama's sovereignty. Still, he highlighted the fact that the canal is of great importance to the United States.

Sen. Warner then asked Stavridis what he hopes to achieve in Venezuela.

Stavridis replied by stating that historically, the US has enjoyed good relations with Venezuela. Still, the country's recent ties with Cuba, Iran, Syria, and Belarus are "disturbing." There is concern that Venezuela is influencing a bloc of Latin American countries to be anti-U.S. Venezuela just purchased new arms, including rifles and jets, from Russia. Oil money is also a big concern in the region. Due to all this, Venezuela's actions "have to be of concern."

The ranking Democrat, Sen. Carl Levin (D-Michigan), attended the hearing but did not pose any questions to Stavridis.

Sen. John McCain (R-Arizona) attended but did not pose any questions to Stavridis.

Sen. Jack Reed (D-Rhode Island) did not pose any questions to Stavridis or the other nominee, General Craddock. He only stated his "disappointment" in Craddock's refusal to discipline Gen. Geoffrey Miller for detainee abuse that allegedly occurred while he commanded the Guantanamo prison facility.

Sen. Ben Nelson (D-Nebraska) asked Stavridis to elaborate on the current situation in Cuba, particularly Fidel Castro's health and the probability of his brother, Raúl, might take power for good.

Stavridis replied that "Cuba is front and center" and it will be at the center of his work. He said he is hopeful of a peaceful transition to a democratic regime, but that he is not hopeful that this will happen anytime soon. Raúl will take the reins of power and "very little will change." Cuba is facing many problems. The country, he said, has a very weak economy that is only propped up by Venezuelan oil subsidies, there are over 800 migrants a year to the United States, and Cuba is a state sponsor of terrorism. In taking action, the "U.S. will support the Cuban people."

Sen. Nelson then asked Stavridis to comment on Nicaragua and Daniel Ortega.

Stavridis stated that "I am not an expert at all" on Nicaraguan politics. But it is common sense to state that Ortega is an opponent of the United States. Although he conceded that the elections appear to be fair and that Nicaragua is a sovereign nation, he is "very concerned" about the linkage between Nicaragua and nations like Cuba and Venezuela, in what he referred to as an "anti-U.S. bloc."

Sen. Nelson posed a third question to Stavridis regarding the IMET program [International Military Education and Training, the main source of U.S. funding for non-drug military training in Latin America]. He stated that he initially thought that the United States was doing other nations a favor with the program. Now, he believes that the United States is the beneficiary of the IMET program. Furthermore, if the United States does not continue with the program - which has been suspended in twelve Latin American countries who do not exempt U.S. personnel in their territory from the International Criminal Court - then nations like China will step in and offer the training.

Stavridis responded to this question after Gen. Craddock already addressed it. Craddock stated that we want servicemen to be protected. The United States is losing engagement opportunities with other cultures, and that the United States benefits from foreign military personnel coming here to see our culture and our democracy. We are losing this in key countries. Stavridis stated that he "associates" himself with all of General Craddock's comments.

Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) raised a concern about Hezbollah being "in our backyard," asserting that the terrorist organization can easily expand its base of actions to the Western Hemisphere. What should we be doing?

Stavridis responded that he has read many reports, both classified and unclassified, about Hezbollah's presence in Latin America. It appears that "Hezbollah has a foothold" in the Southern Command's area of responsibility, especially in the tri-border area shared by Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina. The organization is largely concerned with financing and fundraising in the region, but this could come to include human trafficking. There have been reports of surveillance at the Panama Canal. This is cause for "real concern." The United States' role is "to be plugged into intelligence," which means it has to work with partners, both on a one-to-one basis and regionally. The United States needs to fortify alliances and to be very aware of the situation.

Sen. Cornyn then asked about narco-trafficking and terrorism in Colombia. The FARC, he said, is setting up a safe haven in Venezuela. He asserted that the United States' aid, namely in coca eradication, has been very helpful. What should we do about these recent developments with Venezuela, a nation that associates itself with U.S. enemies?

Stavridis started by saying that "Colombia has made tremendous progress" over the past four or five years, adding that the military is handling the FARC, the AUC is demobilizing, and the economy is doing well. The United States has to support Colombia in strengthening its borders. The issue is "of concern." Stavridis stated that he could not say much more because much of the intelligence is classified.

Sen. Cornyn agreed with his comments, adding that the Department of Defense has to protect U.S. borders (with all of Latin America) by improving use of technology.

The Chairman concluded the panel by thanking both nominees for their "direct answers."

-----------

Joint Oversight Hearing (Government Reform Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security, and the International Relations Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere)

House Rayburn Building

September 21, 2006 11:30 AM

"The Need for European Assistance to Colombia for the Fight against Illicit Drugs"

House Republicans, faced with continued high levels of coca cultivation and cocaine trafficking in Colombia, have not chosen to reconsider their strategy. Instead, they have begun to blame Europe, where demand for cocaine is rising. They charge that European donors have failed to match U.S. aid to Colombia, which is overwhelmingly military in focus, with similar levels of so-called "soft" aid to fight poverty and strengthen civilian institutions.

Opening Statements

Rep. Howard Coble (R-Texas), chairman of the Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security Subcommittee

Rep. Coble said it is believed that 40-60% of Colombian cocaine finds its way to Europe because it is more "geographically convenient" due to the European Union's open borders. The price of cocaine per kilo in Europe is three times that in the United States. The DEA reports that the FARC and the AUC are penetrating Spain. Europe needs to recognize the "imminent danger" of these groups. The chairman stated that he was "disappointed" that the EU members who were invited to testify did not come.

Rep. Dan Burton (R-Indiana), chairman of the Western Hemisphere Subcommittee

Rep. Burton stated that Colombia is at a "critical junction." Spain and Portugal have become "the portals" to Europe. The "drug flow to Europe is undermining" all of the United States' efforts in Colombia. "I hope somebody in Europe is listening, because they should be here today." Europe must begin to pay its pledges for "soft-side assistance" in Colombia.

Rep. Bobby Scott (D-Virginia), ranking Democrat on the Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security Subcommittee

Rep. Scott stated, "My hope is that Europe will do a better job" than the United States has done. The United States has spent billions on security and the military instead of social programs, like education. The United States may have helped increase the supply of cocaine by breaking up large cartels into smaller, less detectable ones.

Rep. Eliot Engel (New York), ranking Democrat on the Western Hemisphere Subcommittee

Representative Engel stated that the United States needs to cooperate with Europe on many matters and current issues - Iran, Afghanistan, and Colombia. "I hope this hearing will be viewed positively on the other side of the Atlantic." The hearing should highlight commonalities instead of looking at differences.

Rep. Coble introduced the three witnesses - Michael A. Braun (Chief of Operations - DEA), Sandro Calvani (UN Office on Drugs and Crime), and, in absentia, Rosso Jose Serrano (Former head of Colombia's National Police, now Ambassador of Colombia in Austria)

Mr. Braun

Cocaine trafficking to Europe can be directly linked to Colombia. The single most important objective is to dismantle cartels. Cartels rule and operate like terrorist organizations, using fear, corruption, and violence. No state in the world has stronger laws than the United States. Because of this, the last thing a trafficker wants is "to face justice in U.S. courthouses." The United States should be proud of this.

Dr. Calvani

The lack of government control of territory allows for the continuing growing of coca. Eradication must be backed with strong economic incentives for farmers. A current project gives farmers $265 per month on a three year basis. The results have been very positive. 80% of the coca plants eliminated have been eliminated for good. Only 0.9% of these farmers say they will go back to cultivating illicit crops. Still, nations, especially in Europe, must work to reduce demand.

Major Lopez (speaking on behalf of Ambassador Serrano)

UN reports show there is an increase in cocaine consumption in Europe, especially in the UK and Spain. It is important to charge the EU to take action and recognize the "shared responsibility" of fighting cocaine trafficking.

Questioning

Rep. Coble: Portugal may surpass Spain as the port of Europe. Does the DEA have an office there?

Braun: The DEA is looking into it, but currently has a "hiring freeze." People from the Madrid office will visit Lisbon regularly.

Rep. Coble: How much does trafficking influence terrorism?

Braun: "Franchised terrorist cells" must fund their operations and many do it through the $322 billion drug industry. The Tri-Border Region is a "breeding ground for terrorism."

Rep. Scott: How much is the United States spending on source-control in Colombia?

Braun: A lot. (He was not aware of the exact numbers.)

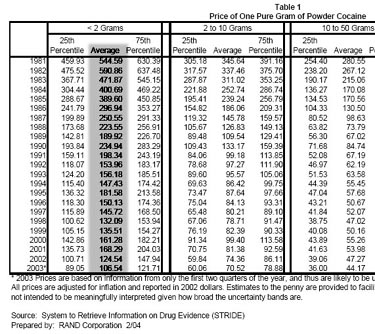

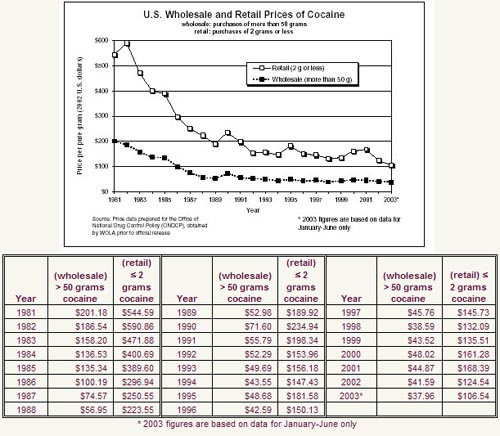

Rep. Scott: What is the trend in the cocaine price on the streets of the United States?

Braun: It remains about the same while the purity has declined.

Rep. Scott: How much supply would we have to reduce to have an effect on the price on U.S. streets?

Braun: The DEA doesn't measure success in price. It measures success in the disruption of cartels. Mr. Braun stated that many reports would refute Mr. Scott's numbers.

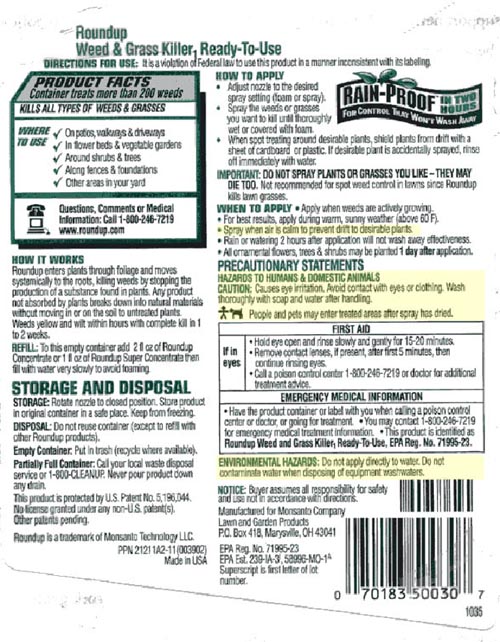

Rep. Steve Chabot (R-Ohio): Chabot stated that he went to Colombia and saw the military and police counter-drug units and was impressed with their work. European countries have opposed aerial spraying and have adopted an"environmental attitude." The spray is "'Round-Up,' so it's not like we don't know what it is." Manual coca "plucking" is very dangerous.

Lopez: In a national park, terrorists were killing individuals who were manually eradicating coca. 19 soldiers, 10, police officers, and 12 civilians were killed. In the end, the park had to be sprayed.

Rep. Engel: Is the U.S. counter-drug policy (Plan Colombia) working?

Braun: "When we hit the traffickers hard," they have the ability to bounce back. They have tremendous potential margin.

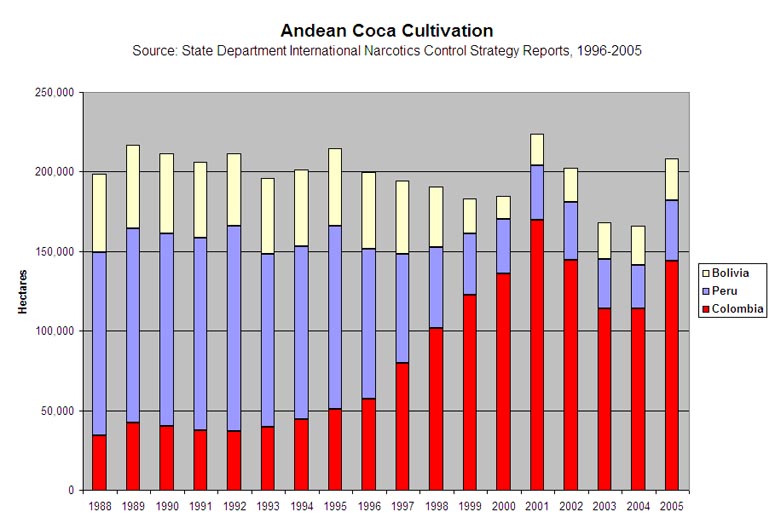

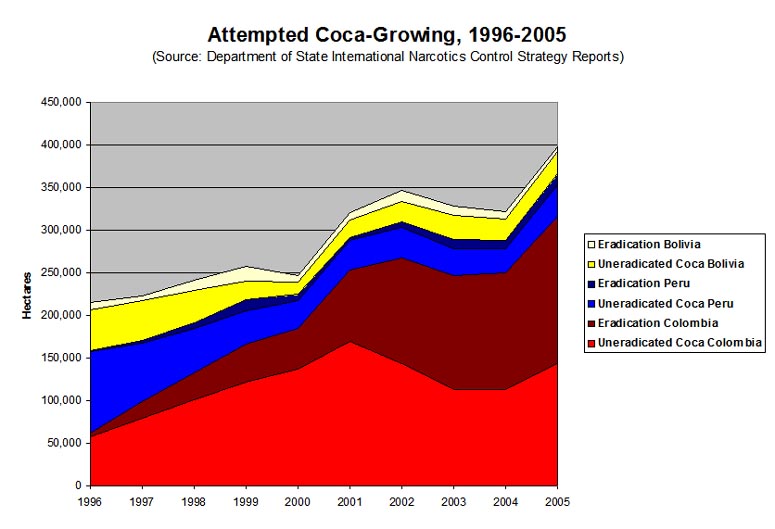

Engel: To what extent has Plan Colombia resulted in an increase of cocaine trafficking from Peru and Bolivia?

Braun: (He did not have any numbers).

Engel: Plan Colombia is controversial in Europe. What are the criticisms?

Calvani: They say the US and Colombia do not consult with them. They want to apply alternative development programs to Colombia (similar to those applied in Laos and Thailand).

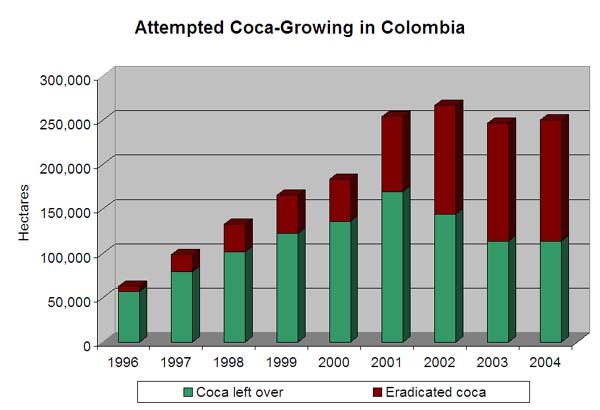

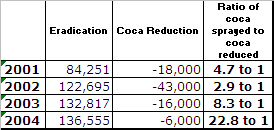

Rep. Coble: Colombian cultivation has increased by 8%. Why has eradication become harder?

Calvani: There has been only a "very slight" increase after a reduction of 51% over the past few years. Alternative development programs have been reduced and demand for cocaine has not decreased. Production in Bolivia and Peru has gone up. Also, people are going into the forest and are planting smaller plots of coca.

Rep. Coble: Cocaine flow to Europe is massive. How many Spanish anti-drug police are in Bogota?

Lopez: There is one Spanish anti-drug police officer and 125 DEA agents.

Rep. Scott: Can you comment on the health implications of spraying?

Calvani: So far, it has not been possible to detect any effect. The product used to spray is widely used in Colombia and the United States.

Rep. Coble: What does organized crime in Russia have to do with the increase of cocaine in Europe?

Braun: It isn't a "significant threat."

Calvani: They are involved in other drugs, like heroin from Afghanistan.

Burton: Doesn't the increase of cocaine in Europe undercut the United States' work? What does the DEA have to say?

Braun: He would have to think about the question.

The Chairman adjourned the hearing.

Posted by isacson at 11:19 PM | Comments (0)

September 20, 2006

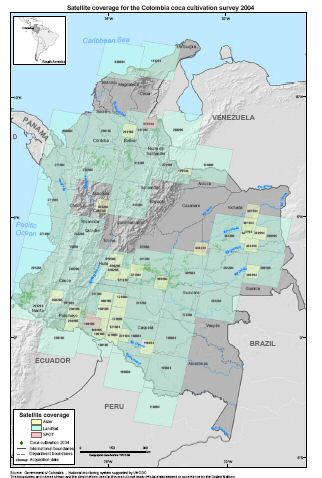

Maps of poverty, coca, fumigation and alternative development

In a conversation today, a House staffer preparing for tomorrow's Colombia hearing asked, "wouldn't it be nice to see the following information side-by-side on a map?"

Yes, it would. Here are four graphics showing poverty levels, coca-growing, fumigation and alternative-development spending by department in Colombia. To see all four on one page, download this PDF file (106KB).

Posted by isacson at 04:03 PM | Comments (5)

September 19, 2006

Where in Colombia does U.S. military aid go?

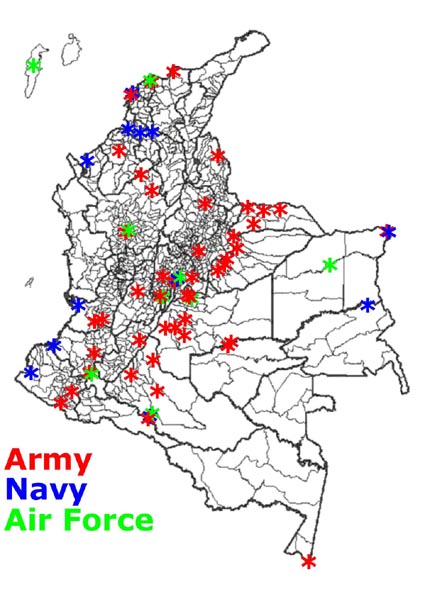

| The map below shows the locations of the vetted recipient units from Colombia's army, navy and air force. |

|

The so-called "Leahy Law" is a provision that has appeared in the U.S. foreign aid bill every year since 1997. Named for its principal proponent, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vermont), its purpose is straightforward. It states that if a foreign military unit includes people who have committed gross human-rights violations, and they are not being credibly investigated, tried or punished, then that unit cannot receive U.S. assistance.

The Leahy Law is not frequently invoked, though it has on occasion forced the U.S. government to refuse aid to army units in Colombia, or to cut off aid to units already receiving it (as happened in January 2003, when an air force command saw its aid cut off for non-cooperation with authorities investigating the 1998 Santo Domingo massacre).

In order to comply with the Leahy Law, the U.S. embassy in Colombia (and, presumably, in every country that gets military aid) must keep a database of individual military personnel who face credible allegations of human rights abuse, and must ensure that none of these names appear on the roster of a military unit being considered for U.S. assistance. This process is called "vetting" the unit.

We had never seen a list of which units had been vetted and approved for U.S. aid - until now. Thanks to the efforts of the Fellowship of Reconciliation's Colombia Program, we now have recent lists of all Colombian military and police units:

- That have been vetted and approved for assistance, and

- That are using U.S.-provided helicopters.

A few quick notes about these lists:

- If a unit does not appear on the list of approved units, that doesn't necessarily mean that the U.S. government has refused aid for human-rights reasons. It does mean, however, that the unit is not getting U.S. aid.

- When the aid in question is training (as opposed to weapons, equipment or intelligence), the definition of "unit" becomes much more flexible. The U.S. government only considers the human-rights background of the individual who has been proposed for training. The individual is the "unit." It is conceivable, then, that an individual from a notoriously abusive unit can receive training, as long as his name does not appear in the vetting database.

- It was surprising to see the 11th Brigade listed. This unit is based in Montería, Córdoba, and its area of responsibility is one of the paramilitaries' principal historic strongholds. Yet the 11th Brigade has almost no record of combating the paramilitary groups that operate in its midst.

- For the most part, other units that operate in paramilitary-heavy areas - the 17th (Urabá), the 4th (Antioquia), the 5th (Magdalena Medio and Catatumbo), the 14th (Magdalena Medio), and the 10th (Cesar) - do not receive assistance. Exceptions include the above-mentioned 11th Brigade, the 16th Brigade (Casanare), and naval units in Sucre.

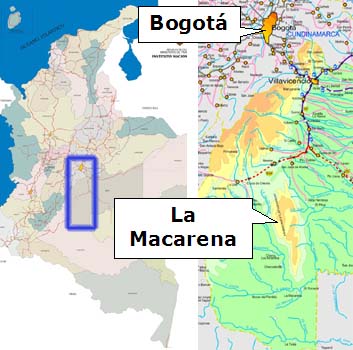

- Many recipient army units are concentrated in the southern Colombian zone where the "Plan Patriota" offensive has been occurring (Caquetá, Meta and Guaviare departments, including the former demilitarized zone where peace talks with the FARC took place between 1998 and 2002). Another zone of concentration are the oil-producing departments of Arauca and Casanare. (In 2002, the U.S. Congress approved a Bush administration request for $100 million in military aid to protect an oil pipeline in Arauca.)

- Surprisingly, none of the military units in the department of Putumayo - where Plan Colombia began in 2000 - is receiving aid, with the exception of the Navy Riverine Battalion and an Army Counter-Narcotics Brigade that only spends some of its time in Putumayo.

- In the list of units cleared to use helicopters, "TF Omega" is the task force involved in the Plan Patriota offensive. "PCHP" stands for "Plan Colombia Helicopter Program."

Posted by isacson at 07:16 PM | Comments (3)

September 11, 2006

Fumigation and "defoliation"

The International Journal of Remote Sensing is a periodical that you'll rarely find on our reading list. But we were very interested to read a paper recently published there about "Defoliation and the war on drugs in Putumayo, Colombia." An abstract of the paper is available here, but unfortunately you have to pay to read the whole thing.

Much of the paper looks like this:

Or like this:

But the authors' conclusion is easy enough to understand:

[A]erial spraying of defoliants under the US ‘Plan Colombia’ programme impacted broad swaths of the landscape and had the unintended consequence of defoliating contiguous and interspersed native plant and food crop parcels. ... The complex spatial organization of the Colombian coca-producing landscape appeared to confound the spraying of defoliants, and as demonstrated here, many non-coca land cover classes have been affected adversely.

In other words, satellite imagery seems to vindicate all those Colombian campesinos claiming that the U.S.-funded herbicide fumigation, through inaccuracies and spray drift, destroys legal crops, alternative-development projects, and nearby forest.

This finding seems to contradict the State Department's regular certifications to the U.S. Congress that such environmental damage is not happening. The last certification, for instance, reads as follows:

The Government of Colombia regularly conducts studies to assess the spray program's environmental impact through ground truth verifications to estimate spray drift and the accuracy of the spray mixture application and during verification of all legitimate complaints about alleged spraying of crops or vegetation that are not coca or opium poppy. After one recent verification, the Government of Colombia’s Ministry of Environment, Housing, and Territorial Development characterized spray drift in the following fashion:

The drift effects that were observed in areas visited on a random basis were temporary in nature and small in extent, and basically consisted of partial defoliation of the canopy of very high trees. No complementary collateral damage from spraying activities was observed at the sites selected and verified. In sprayed areas that were subsequently abandoned, it was noted that vegetation was starting to grow again, the predominant types being grasses and a number of herbaceous species (Attachment 2, p. 4)

The Department of State believes that the program’s rigid controls and operational guidelines have decreased the likelihood of adverse impacts of the eradication program on humans and the environment and that the herbicide mixture, in the manner it is being used, does not pose unreasonable risks or adverse effects to humans or the environment.

The International Journal of Remote Sensing paper charges that the problem is far more widespread than the U.S. and Colombian governments maintain, and that the environmental impact may indeed be quite serious.

The region is classic humid tropics, with cloud cover present almost every day. This has made both monitoring the situation more difficult and, conversely, hiding the effects from the public simpler. While this research should not be used to indict the UNODC or the organizations responsible for spraying, it should serve as a warning that the published reports on drug war results are open to interpretation and that some of the anecdotal, and usually dismissed, claims of misapplication of spraying may, in fact, be true.

Add to this the widespread anger and resentment in areas where development aid has failed to keep up with the spray planes. Yet even with all this collateral damage, the ends can't even be said to justify the means. The hugely expensive fumigation program has still failed to reduce coca-growing in Colombia.

Posted by isacson at 03:20 PM | Comments (2)

September 08, 2006

The paramilitary "extraditables"

Thanks to a communiqué [PDF] put out last week by the Colombian presidency, there is finally a public, more-or-less comprehensive list of paramilitary figures who face U.S. government extradition requests for narcotrafficking. It turns out that there are twenty-four of them.

Ten of them are still at large. Here they are, with photos where available.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(No photo available) |

|

(No photo available) |

|

(No photo available) |

|

|

|

(No photo available) |

|

|

|

(No photo available) |

|

(No photo available) |

|

|

|

An August 30 article in El Tiempo adds the names of eight additional individuals facing extradition whom the paramilitaries have identified as members of the AUC. All of them already in Colombian jails.

- Álvaro Antonio Padilla Meléndez, alias "El Topo," Bloque Resistencia Tayrona;

- Álvaro Padilla Redondo, Bloque Resistencia Tayrona;

- Eduardo Enrique Vengoechea, Bloque Resistencia Tayrona;

- Fredy Castillo Carrillo, Bloque Resistencia Tayrona;

- Héctor Ignacio Rodríguez Acevedo, Bloque Resistencia Tayrona;

- Huber Aníbal Gómez, Bloque Resistencia Tayrona;

- Jhony or Jhon Eidelber Cano Correa, Bloque Resistencia Tayrona;

- Jhon Alexánder Posada Vergara, Bloque Norte.

Posted by isacson at 03:02 PM | Comments (0)

September 04, 2006

If the Democrats take the House...

Front-page stories in yesterday's Washington Post and today's New York Times report that the Republican Party, dragged down by President Bush's unpopularity, is increasingly likely to lose its majority control of the House of Representatives when the United States elects a new Congress in November.

In the U.S. system, the party that holds a majority of a congressional chamber - even if it is just a one-seat majority - controls almost everything the chamber does. That party gets to name the speaker of the House and the chairmen of all committees. That party decides which bills get debated on the floor and sets the rules for debate. That party's committee chairmen decide which bills get considered, draft the text of appropriations bills, decide the subject matter for hearings and have the power to subpoena witnesses. The balance between parties makes an enormous difference in the U.S. congressional system.

The election is more than sixty days away, and it is entirely possible that the Republicans will manage to hold onto their majority. However, if the Democrats do manage to take back the House for the first time since 1994, U.S. policy toward Colombia could change significantly.

If the Democrats win back the House, the likely leadership of the chamber, and the chairmen of all committees with jurisdiction over Colombia policy, will be made up of people with long records of criticizing the current U.S. policy toward Colombia. (Skip down to see who they are and what their records are.)

Most have expressed concerns about the lack of results against drugs, the Colombian armed forces' human-rights record, the open-ended U.S. mission, and the need for more development assistance. Most have consistently supported legislative efforts over the past six years to reduce the amount of military aid going to Colombia and to do more to address poverty and human-rights abuse.

It has been reported that the Bush administration plans to begin reducing aid to Colombia in 2008 or 2009. Because a Democratic House would probably approve more money for foreign aid worldwide, it would be less likely to implement such cuts - or at least it would not cut aid as deeply as a Republican Congress might.

While the overall amount of aid from a Democratic House would likely be larger, though, the ratio between military to economic aid would probably be significantly different from the current 80 percent to 20 percent split. U.S. aid would become less military in focus, with more funding for priorities like alternative development, civilian governance, judicial reform, aid to the displaced and human rights. Aid would be more strongly conditioned on the Colombian military's human-rights performance, and the aerial herbicide fumigation program, which has not reduced coca-growing, will come up for particular scrutiny. A Democratic chamber would also increase investment in drug demand reduction at home, particularly treatment for addicts.

(The fate of the free-trade agreement the two countries have signed is harder to predict. However, it's worth recalling that CAFTA was barely ratified last year, passing the House by only one vote. And only 15 Democrats voted for it.)

Here are the House Democrats who would be likely to take over leadership positions if their party wins control of the House in November. In one of her last duties this summer, now-departed intern Christina Sanabria compiled each member's record on the ten Colombia-related amendments that have come to a vote since aid to Plan Colombia was first debated in 2000. (A description of each amendment is below, and all members' Colombia voting records are here.)

| Amendment descriptions |

| 2006:

|

| 2005: |

| 2003:

|

|

|

| 2002:

|

| 2001:

|

|

|

| 2000:

|

|

|

Posted by isacson at 11:11 PM | Comments (2)

August 31, 2006

Still swatting flies in Caquetá

In a post to the Democracy Arsenal blog, I discuss USAID's plans to ignore Caquetá department completely, even while the "Plan Patriota" military offensive continues there. It seems to say a lot about how little the U.S. government understands the challenge of dealing with insurgencies.

Does USAID really mean to say that it will only invest in zones where the economy is already viable and where guerrilla presence is low? Does the United States make similar choices in Iraq, too? ("Forget about the Sunni Triangle, let's get the electricity flowing in the few towns where the locals are happy to have us.") If so, that would explain quite a bit.

Posted by isacson at 05:21 PM | Comments (1)

August 29, 2006

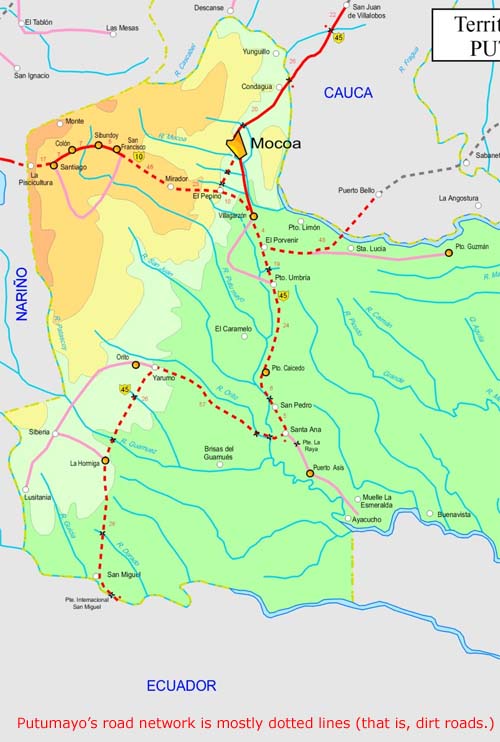

Putumayo's white elephant, or how not to win hearts and minds

While driving through the troubled department of Putumayo in southern Colombia late last month, our group decided to branch off the main road to pay a quick visit to Orito, the main town in the municipality (county) of the same name. We had heard that one of the largest projects funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Putumayo, an animal-food concentrates processing plant in the town, was having some difficulties, and we hoped to be able to find out what was going on.

|

|

|

The plant's concept appeared to make sense: take crops that are easily grown in Putumayo, like yuca and corn, and turn them into food for cows, pigs, chickens and other livestock. USAID and its contractors helped to set up a publicly traded company to run the plant and invested somewhere in the neighborhood of US$2 million to build the facility, buy machinery and perform studies (feasibility, environmental impact, etc.).

This high-profile project, it was hoped, would help wean thousands of Putumayo's farmers away from coca-growing, while turning a profit for its shareholders. It greatly raised expectations among a population battered by massive coca cultivation, relentless fumigation, chronic government neglect and constant violence at the hands of illegal armed groups.

We found the concentrates plant easily enough, as it was located right next to Orito's oil refinery and the base of the local Army energy-infrastructure protection battalion. It is a great-looking facility, modern and clean, with intricate machinery, a cafeteria, meeting spaces, and a big plaque thanking USAID for making the whole thing possible.

Everything looked great, except the whole scene was strangely quiet. The expensive-looking machinery was idle. There were no animal-feed concentrates, yucca or corn to be seen anywhere. The plant was not functioning.

The big building was not empty, though. About forty people were using it as a meeting space. When we arrived, several people had gathered for a job-training workshop organized by a local non-profit. Others, including two Orito council members, were assembled elsewhere in the building. When they saw us arrive, all stopped what they were doing and gethered around us - and especially me, the lone gringo in the group.

Once I explained that I wasn't from the U.S. government, but an independent investigator trying to figure out what happened, everyone started talking at once. It was like being hit by a big wave of anger and frustration. Things soon calmed down, and I tried to take notes as quickly as I could. This is more or less what the residents of Orito told me.

- The concentrates plant cost about 6 billion pesos (US$2.5 million) to establish. It opened in late 2003 and shut its doors in mid-2005. There are no plans to re-open it. The plant's machinery is already being sold off, and some had already been carted away. Residents who had been convinced to invest in the plant had lost money.

- The main reason the concentrates plant failed was a lack of inputs. Nobody wanted to sell it yuca or corn because it offered to buy it at prices considered to be ridiculously low.

The plant offered to pay 120,000 pesos - about US$50 - for a ton of yuca. That's 5 U.S. cents per kilo or 2.2 cents per pound. The same kilo of yuca could be sold in local produce markets for about eight times as much money. I was told that the cost of renting a vehicle and transporting that ton of yuca through roadless Putumayo to the processing plant would eat up more than one-third of those 120,000 pesos.

It made no sense for local farmers to sell yuca or corn to the concentrates plant, when they were guaranteed to lose money at the prices offered. The plant's managers apparently took a "take it or leave it" attitude, not budging on the price (and it is possible that they could not make money at a higher price). The farmers, of course, were happy to "leave it," selling yuca at better prices elsewhere, or braving the U.S.-funded herbicide fumigations and re-planting coca. - The plant was plagued by other problems that should have been foreseen. The machinery, most of which was apparently used and refurbished, never worked at anywhere near top efficiency. Storage of yucca and seeds was a problem in Orito's very humid climate.

- Those with whom I spoke wondered how the idea of a concentrates plant was chosen, alleging that the community was never asked. Others wondered why it was located in oil-producing Orito, when better soils for growing yuca and corn were located in municipalities about an hour's drive to the south.

Since 2000, U.S.-funded planes have sprayed herbicides over 155,534 hectares (about 390,000 acres) of Putumayo, making it the second most-fumigated of Colombia's thirty-two departments during this period. The "stick" of fumigation has been strong and swift, but the "carrot" of development aid has not only been smaller - only 20 percent of U.S. aid to Colombia is non-military - but it has been slower to arrive, haphazardly planned, and has largely failed to improve lives and livelihoods. "Orito today is in its worst economic crisis," a councilmember told me.

After about half an hour, we left the plant and got back on the road. I lamely promised those assembled at the plant that I would at least inform my fellow citizens and my lawmakers about what I saw there.

My nauseating experience in Orito was made possible by one of the most frustrating things about watching U.S. policy unfold in Colombia over the past several years: its systematic undervaluing and neglect of all things non-military.

For planners of U.S. assistance to Colombia, non-military programs have always been an afterthought. Four out of five dollars in U.S. aid goes to Colombia's armed forces, police, and fumigation program. Policymakers have placed a far lower priority on the rest of the aid, which is intended to support governance and development.

Too often, these funds go to programs that are improvised, uncoordinated, left entirely up to contractors, carry high overhead costs, and appear to ignore completely the lessons of similar efforts taken elsewhere. Oversight is weak, dubious claims of success go unquestioned, higher-level officials show little interest. It's easy to get the impression that nobody in charge of these projects cares whether they succeed or not: the point is to spend the money and demonstrate that an objective was fulfilled. The Orito concentrates plant is a perfect example.

The U.S. and Colombian governments have claimed to be pursuing many goals in Colombia, from fighting drugs to fighting guerrillas to simply making Colombia a more just, lawful, prosperous society. To achieve any of these goals, a strategy will fail if it lacks a major investment in governance and development - especially in the vast, stateless rural areas where armed groups and drug crops thrive. Spray planes and military sweeps cannot do it on their own.

But look no further than Putumayo to see the tragedy of alternative development in Colombia. Plan Colombia began in 2000 with Putumayo in mind: at the time, this province of 350,000 people had more coca than any other in the country, and was overrun by guerrillas and paramilitaries. A U.S.-funded "push to the south" would insert new military units in Putumayo and initiate a massive campaign of aerial herbicide fumigation. Next would come aid to help the region's coca farmers to switch to legal crops.

Yet five years later, the United Nations found that Putumayo was still the country's number-three coca-growing department. Today, it is still overrun by armed groups, and it is safe to say that Putumayo's population has not experienced a flowering of affection for its government institutions.

It is not news that progress will be only temporary until Colombians who live in depressed rural areas like Orito - a minority of the population living in the majority of the country's territory - can trust their government to protect them, to enforce laws and to make a functioning legal economy possible. Counter-insurgency experts have said for decades that "the people are the center of gravity."

But in Orito, Putumayo - right in the middle of one of the main battlegrounds for the Colombian government's U.S.-aided counter-insurgency effort - the people I talked to are very, very angry. The angrier and more distrustful they get, the more likely it is that even the small security gains that the Uribe government has achieved will be reversed.

Posted by isacson at 12:44 PM | Comments (2)

August 23, 2006

Colombian contractors in Iraq

Here are some excerpts, translated into English, from the shocking and sad cover story in this week's edition of the Colombian magazine Semana. It tells of thirty-five retired Colombian military officers who were recruited to serve as security guards in Iraq.

A subsidiary of Blackwater USA, the major U.S. contractor whose private guards have even protected U.S. generals in Iraq, recruited the Colombians with promises of salaries of $4,000 per month - more than most doctors or lawyers earn in Colombia. After undergoing training on a Colombian military base (!), they were rushed off to Baghdad - where they found that their salaries would be only $1,000 per month. When they complained, the U.S. company took away their return tickets.

Here is the story. There is much more in the Spanish version that is worth a read as well, such as the reaction of these officers, all of them veterans of Colombia's violence, to the incomparably worse security situation in Iraq ("This is hell: there are bombings all the time, shots, helicopters near and far, sirens day and night. There is no rest. One feels a permanent tension in his chest.")

“The group of 35 of us, and another 34 that arrived about two weeks later, we want to return to Colombia, but they won’t let us. When they find out that we’ve talked about what they’re doing to us, we don’t know what could happen. But the truth is that the people here in Baghdad are desperate,” said Esteban Osorio, a retired captain of the National Army.

… Retired Army Major Juan Carlos Forero went to an office near downtown Bogotá to submit his resumé. “The company is called ID Systems… it’s the representative in Colombia for the American firm called Blackwater. It is one of the biggest private security contracting firms in the world and they work for the U.S. government,” said Major Forero.

“[At ID Systems] we were received by Captain (Gonzalo) Guevara, who works with that firm and is retired from the Army. He told us that basically we had to provide security for military facilities. He told us salaries were around $4,000 USD per month,” Forero said.

Finally, in early June of this year, the representatives of ID Systems told the recruited Colombians that the time had come. “On the evening of the first of June, they asked twelve of us to meet at the office and told us that we were leaving for Iraq the next day. There they told us that the salary wouldn’t be $4,000, but $2,700. We didn’t like that because we had always been convinced that it would be $4,000, but there wasn’t anything we could do at that point.” Why? Because by then none of them had jobs anymore (they had quit in anticipation of the trip) and were desperate to support their families.

At midnight of June 1, Forero and his companions were made to sign contracts, and were given a copy. “We weren’t able to read anything in the contract. We just signed and left in a hurry because when they gave us the contracts they told us we had to be at the airport in four hours and since everything was so rushed, we barely had time to say goodbye to our families, get our bags together and leave for the airport,” said Forero.

From Bogotá they left for Caracas, from there to Frankfurt, where they waited for twelve hours for a flight to Amman, Jordan, and from there a last plane to Baghdad. “Since in the Frankfurt airport we had to wait so long, we started reading the contract, and there we realized that there was something wrong because it said they would pay us $34 a day. That is, our salary would be $1,000 a month, and not $2,700,” recalls Forero.

… The mission of the group… consisted in replacing a group of Romanian contractors that had finished their contracts. “When we linked up with the Romanians they asked us how much we were being paid, and we told them $1,000.” They responded with mockery. “No sane person in the world comes to Baghdad for only $1,000,” they said.

The Romanians told them that for the same work they were being paid $4,000. That fact gave way to uneasiness among the other contractors on the base. The mood turned hostile against the Colombians because if each soldier establishes his own conditions for fighting in a foreign country, there is always a benefit because in the end they are risking their lives. No one spoke to the Colombians and when they did, it was to offend them and treat them like cheap labor.

On June 9th, before they had spent even a week in Baghdad, the 35 drafted and signed a letter addressed to the ID Systems and Blackwater representatives. In the letter, they said that if they didn’t pay the $2,700 that were promised, they wanted an immediate return to Colombia for the entire group.

The letter in which the Colombians demanded their rights was interpreted as rebellion, and the consequences were unexpected. “When we arrived at the base, they took away all our return flight tickets. After the letter they gathered us together and said that if we wanted to return, we should do it through our own means. Ironically, in a show of antipatriotism, one of the people who was most against us was a former captain of the Colombian Army, (Edgar Ernesto) Méndez, who is the link here in Iraq of the contractor in Colombia,” said retired Captain (Estaban) Osorio from Baghdad.

“To force us to comply with the contract, they began to pressure us. They threatened to kick us out of the base facilities to the streets of Baghdad, where you are exposed to being killed or, in the best of cases, kidnapped,” said Osorio.

…What’s more, when they were hired in Bogotá, the retired military men were told they would have eight-hour shifts. After the protest, the shifts became twelve-hour shifts. When the group complained, the response was that they would lose their potable water or that they wouldn’t receive the same food as the others on the base. At the time of recruitment in Bogotá, they were told that they would have medical insurance, dentists, and access to recreation zones within the base and life insurance for $1.5 million dollars. Just like the salary they were offered, nothing turned out to be true. Then came the health deterioration. “Several have gotten sick or have had accidents and it has not been possible for them to receive medical attention. When we asked for an explanation, the only thing we are told is that our contract does not cover that kind of services,” says Forero.

The contractors insist on the influence that the company has on the Army and the government, and that the company could close the doors for them to find jobs back in Colombia. And the threats go even further. “We are afraid for the consequences, not only that we risk being left without a job when we return to Colombia, but that they have also told us to remember that they have all the information about our families and children and that, simply put, is a threat,” said Forero.

Although the Ministry of Defense, the Army and the United States Embassy in Colombia are aware of the recruitment of retired soldiers, it has been a matter dealt with a low profile in which nobody accepts any responsibility.

The closest to it is that the Defense Ministry and Army staff accept that they’re “doing a favor” by lending (ID Systems) a Colombian military base for the training of retired soldiers that are sent to Iraq. “It’s a company endorsed by the U.S. government that asked the Army for cooperation, which consists of allowing them the use of the base, as long as they do not recruit active personnel. There is no agreement, contract or any other type of relationship with them, and therefore, the Colombian government has no responsibility. Whatever happens between retired soldiers and the company that recruits them is basically an agreement between an individual and a foreign company,” said a high-level government official.

For their part, an official from the U.S. State Department in Washington, DC, determined that “The State Deparment believes that this is a private commercial dispute between the Colombian employees and their employer.” The official said that any other comment should be made by Blackwater. Semana Magazine called Chris Taylor, vice president of that company, over ten times, and sent him a written set of questions but never received a response. It was also impossible to obtain a response from the representatives of ID Systems in Colombia, the retired captain Gonzalo Guevara or the owner of ID Systems, José Arturo Zuluaga.

(All the names have been changed for security reasons.)

Posted by isacson at 08:18 AM | Comments (2)

August 15, 2006

Notes from Putumayo

This was my third visit since 2001 to Putumayo, a small department in Colombia's far south, along the border with Ecuador. I've also taken two other trips very close to Putumayo, one to the Ecuadorian side of the international border, and one to a meeting of Putumayo community leaders just over the departmental border in eastern Nariño.

I keep coming back to Putumayo because there is no better place to gauge the impact, the success or failure, of U.S. policy in Colombia. This province of perhaps 350,000 people is where Plan Colombia basically got started, back in 2000-2001.

At that time, Putumayo had far more coca than any of Colombia's 32 departments, along with a very heavy FARC guerrilla presence, while its principal towns were being methodically, brutally taken over by paramilitaries. Putumayo was the focus of the military "Push to the South" that lay at the heart of the Clinton Administration's big 2000 aid package. Supported by U.S. funds, trainers and contractors, a new Colombian Army Counter-Narcotics Brigade, bristling with helicopters, would clear Putumayo's coca-growing zones of armed groups, while augmented counter-narcotics police would coordinate vastly increased herbicide fumigation. In their wake would come alternative-development programs to help Putumayo's farmers participate in the legal economy.

|

A U.S.-donated Colombian Anti-Narcotics Police Blackhawk parked at the Puerto Asís airport. |

Six years and untold hundreds of millions of dollars later, did the strategy work in Putumayo? No, mostly not, though there are a few bright spots.

Like much else in Colombia, the results in Putumayo tell us that the strategy needs to be very long-term, must consult closely with local leaders and organizations, and must go way, way beyond military operations and fumigation. And by all appearances, these lessons haven't come close to sinking in yet.

Here is a closer look, based on my all-too-brief visit.

The security situation appeared to be better, for now at least, though the last few years have shown that levels of security tend to oscillate wildly between relative safety and extreme danger. Right now, travel along main roads is possible, with the likelihood of running into guerrillas considered to be low. Road travel at night is still inadvisable, though doable.

We passed through more army and police checkpoints than I had seen before, and the security forces' presence was greater in general. Small contingents of soldiers were reliably stationed at key infrastructure points, including the rebuilt bridge over the Guamués River, which the FARC had blown up before my last visit in 2004, forcing us to board canoes to get across. Many of the soldiers and cops we saw were clearly from elite units, judging from their physical size and the quality of their equipment. (The soldiers who patted us down at checkpoints, however, were generally smaller and younger.)

Some small towns along the main road that had no police presence before, such as El Tigre or Buenos Aires, now had police stations. Also notable, especially in the oil-producing town of Orito, was the presence of troops from a new energy and road infrastructure-protection army brigade. Soldiers and police in many posts sat behind bags of cement piled high into walls, a bulletproof defense that resembled preparations for a flood.

|

|

Though I've never run into uniformed guerrillas on any of my visits to Putumayo, one usually sees evidence of their activity. Guerrilla graffiti - once so common that it was even spray-painted on the sides of tractor-trailers that had passed through FARC roadblocks - was faded, when visible at all.

There was abundant evidence, though, of the last flare-up of guerrilla violence in the department, at the beginning of this year in the run-up to the March legislative elections. A guerrilla "armed stoppage" (paro armado) halted road traffic between towns for weeks, bringing shortages, while attacks on power lines left much of Putumayo in the dark. Along the main road were burned patches from trucks that the guerrillas set afire for disobeying the stoppage. As on previous visits, blackened trees and pools of sludge indicated places where the guerrillas had recently blown holes in the oil pipeline that follows the main road for much of its length.

|

Faded guerrilla graffiti. |

|

A common sight on the main road - a recently blown-up patch of pipeline with a pool of oil sludge. |

The increased military and police presence - in part a response to the wave of violence at the beginning of the year - had made conditions more secure in general. However, several local leaders indicated, flare-ups of guerrilla activity were still common and could happen at any time. One likely reason was that a U.S.-supported military offensive immediately to the north of Putumayo, a two-year-old effort known as "Plan Patriota," had forced many guerrillas to relocate, increasing their numbers particularly in border departments like Putumayo, Nariño, Vaupés and Norte de Santander. By all accounts, the guerrillas' grip on Putumayo's rural zones - the majority of the department's territory, away from the principal towns, the main road and the most-traveled rivers - was unchanged.

While the frequency of FARC attacks in the department was reduced and limited to more remote areas, their intensity when they do occur has been greater. Body counts per attack have been much higher and damage to infrastructure has been more costly. Just before I arrived, guerrillas had kidnapped thirteen medical personnel in the rural zone of Puerto Asís municipality, eventually releasing all but one of them. While I was present, combat was taking place along the Ecuadorian border; one night in La Hormiga I could hear the periodic soft thud of what sounded like mortar rounds going off many miles away to the south.

For the most part, I heard few strong complaints about the increased military and police presence in Putumayo. Nobody with whom I spoke denounced cases of serious abuse or large-scale corruption at the hands of police or soldiers, with the exception of some instances of rough treatment or disrespectful language.

Two issues, though, require attention. First, several indigenous leaders expressed concern about the recent construction of a military installation, part of the government's larger Center for Attention to the Border Zone (CENAF), on land belonging to an indigenous reserve in San Miguel municipality. Though I've found little additional information about this new base, I heard numerous complaints about the way in which it was installed - with a refusal to dialogue and an insistence on national security priorities and the government's right to be present wherever it wishes - and concerns that the CENAF leaves the indigenous reserve more vulnerable than ever to guerrilla attack.

The other issue was a general consensus that military and police efforts against "former" paramilitaries in Putumayo are still minimal to nonexistent. Since 1999-2001, paramilitaries have dominated Putumayo's main towns and vied with the FARC for income from coca cultivation and processing. They have maintained this dominance through a combination of brutality (first massacres, then selective killings and "social cleansing" that continue today), providing security for urban residents and businesses, and a nearly complete absence of opposition from the security forces. (This absence was chillingly documented in Human Rights Watch's 2001 report, "The Sixth Division.")

At some point around 2002 or 2003, the leadership of the Putumayo paramilitaries shifted from Carlos Castaño's Córdoba and Urabá Self-Defense Groups (ACCU), which claimed to seek less involvement in the drug trade, to the powerful Central Bolívar Bloc (BCB), which actively sought narco funding. Though the BCB officially demobilized early this year, its Putumayo branch appears to have continued its activities with few changes. They still dispute control over drugs and territory with the guerrillas, and continue to carry out selective killings on a near-daily basis. "Macaco's guys are still everywhere," said one interviewee, referring to the BCB's most feared, if not most visible, leader.

While this was the first time I visited Putumayo without seeing uniformed paramilitaries, their plainclothes presence was still in evidence. "Paraco," mouthed a traveling companion as we sat in a Puerto Asís restaurant, nodding nervously toward two men passing slowly by on a motorcycle.

A few miles north of Puerto Asís, close to the large military base in the suburb of Santana, sits Villa Sandra, a large compound with a big house, a pond and recreational facilities. During the paramilitaries' bloody takeover of Putumayo's town centers, and then during the beginning of Plan Colombia's execution, Villa Sandra was the paramilitaries' center of operations. Everyone in Puerto Asís - except, apparently, the military and police - knew that the paras were headquartered there, and that many of their victims were taken there and never left.

During my 2001 visit to Putumayo, Villa Sandra was very much in use. When I returned in 2004, it was abandoned, and remains that way now, with its facilities in evident disrepair behind a high chain-link fence. Many in Putumayo believe that an inspection of the compound's grounds would reveal much about the paramilitaries' activities in the zone - including, in some likelihood, mass graves. That Villa Sandra remains untouched and uninvestigated is eloquent evidence of the paramilitaries' continued influence over Putumayo, despite the recent demobilizations.

If the security situation is mixed but trending slightly better, patterns of coca cultivation are mixed but trending worse. When I visited Putumayo in early 2001 after Plan Colombia's first round of spraying, the department was Colombia's undisputed coca capital - the UN measured 66,000 hectares of the plant there in 2000. Coca was in abundance, with large plots easily visible from the main road, especially in the Guamués River valley.